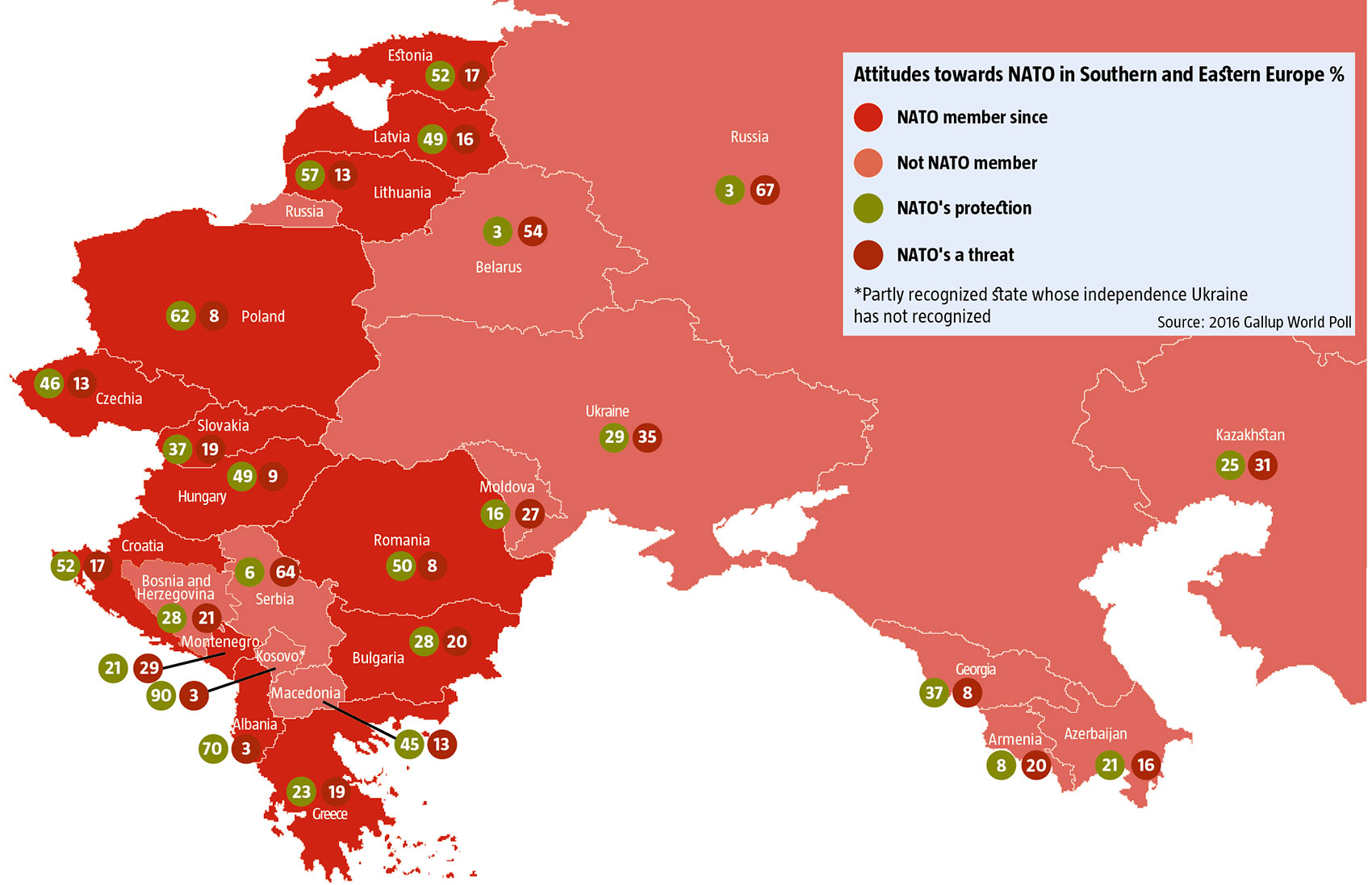

In early 2017, the American pollster Gallup published the results of a survey of attitudes towards NATO in countries that once belonged to the socialist camp. The results were not surprising (see Attitudes Towards NATO in Southern and Eastern Europe). It seems that attitudes towards NATO are affected by a number of factors that are generally easy to relate to recent political events. Sometimes we can see Russia’s influence, which has been turning itself into the Alliance’s key opponent once again. Sometimes, such as in Serbia, negative attitudes can reflect actions taken by NATO itself: locals still remember well its 1999 bombardment in response to ethnic cleansing of Kosovar Albanians by Serb forces. In the Balkans, the national factor plays a considerable role in many countries in their relations with NATO. A clear example of this is Bosnia & Herzegovina, which received its invitation to the MAP in 2010. According to UNDP data from 2014, 82% of Bosniaks and 80% of Croatians thought joining NATO would have a positive impact on their country. Only 15% of Serbs feel the same.

Taking another look at the Gallup poll, the most striking fact is that even some members of the Alliance not only don’t demonstrate unanimous support for NATO—they don’t even have a convincing majority in support. Greece is a perfect example: it joined NATO in 1952, but today only 23% of Greeks think the Alliance provides security, while almost the same proportion, 19%, think it’s a threat. The remaining half of the population is neutral about NATO.

Of course, there are diametrically opposed examples, right next door to Greece. In Albania and Kosovo, 70% and 90% of the population see NATO as providing protection. The case of Kosovo is also a reflection of the bombardment of Serbia nearly 20 years ago: where the Serbs saw NATO as an aggressor, the Kosovars saw NATO as a liberator, so for them NATO was obviously providing security. This is also in part the reason for the support seen in Albania, as over 90% of Kosovo’s population is ethnic Albanian. But another factor has also played a role in Albania. In 2016, the UN Development Program (UNDP) ran a survey in Albania, with one purpose being to determine public trust in a range of institutions. As it turned out, support for the country’s political and judiciary systems was very low, at 25-20%. These figures are close to what we can see in Ukraine and other countries with a high level of corruption and relatively low standard of living. Among Albanians, three international organizations made the Top 3 for trust: the EU, the UN and NATO, with nearly 80% of the population expressing trust in them. What’s more, this indicator has been growing year after year.

These are the results long-term cooperation that began almost immediately after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. The Albanian regime was a unique phenomenon even in the socialist bloc: the local leadership managed at various times to quarrel with the USSR, with Yugoslavia and even with China. After that regime collapsed, the country fell into a long period of political instability and managed to pass a new Constitution only in 1998. Yet this did not get in Albania’s way of becoming the first country in the eastern bloc to receive military aid from the United States and the first to unequivocally state its intentions of joining NATO.

In 1995, the Washington Post called all this the “most bizarre military cooperation,” meaning that the biggest military power in the world was working together with what was then considered the smallest, Albania. And although this Balkan state actually acceded to NATO later than many other CSE countries, the impact of this cooperation can be felt to this day. If public opinion is taken into account, it’s Albania and not Greece, as once was, that can be called NATO’s outpost in the Balkans.

RELATED ARTICLE: Rasa Juknevičienė: “The entire country joins NATO, not just the Defense or Foreign Ministries”

In Ukraine, attitudes towards NATO remain controversial. In contrast to Albania, for many years Ukraine made no plans to actually join NATO, even though it began cooperating with the Alliance immediately after declaring independence. Meanwhile, NATO paid little specific attention to Kyiv as well. As a result, a consistently negative image of the Alliance continued to dominate among Ukrainians, which often became a weapon in the hands of politicians who played on fears of various kinds. For instance, the peak of hostility towards NATO in Ukraine was reached, not in the 1990s, but after the Orange Revolution, when political competition reached its peak under the Yushchenko Administration.

The war changed everything. Today, a very modest 30% of Ukrainians think that NATO represents security, compared to 70% of Albanians. In the Gallup report, the authors focused specifically on the example of Ukraine. “In 2014, after the Alliance instituted sanctions against Russia over its annexation of Crimea, for the first time more Ukrainians (36%) thought of NATO as representing security, rather than a threat (20%),” the authors wrote. “However, by 2016, the proportion of respondents who thought it was a threat had grown to 35%, reflecting how tired Ukrainians were from the military conflict, the poor state of their economy, and a growing crime rate.”

In addition to the political factor, one of the main reasons for NATO’s lack of popularity in Ukraine is due to a lack of understanding among ordinary Ukrainians about just what the Alliance is and does. In August 2018, the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Fund published the results of a study that makes it possible to track changes in this issue. First of all, the authors confirmed what Gallup had said. The popularity of acceding to NATO as the best guarantee of national security kept growing steadily, from 13% in 2012 to 47% in 2017, after which the picture did not change much. This past August, however, the share slipped to 42%. At the same time the popularity of a military union with Russia collapsed from 31% to 6%. What seems to be growing in the meantime is support for the idea of a neutral Ukraine: the share of those in favor fell from 42% in 2012 to 20% by 2014, when the conflict in Donbas was at its worst. Yet by August 2018, this group had grown back up to the levels it was before the war, with 35% of Ukrainians preferring non-bloc status for Ukraine.

If there is talk of a referendum on accession to NATO, the latest poll results suggest that this is the best time for those who support membership: 44% in favor and 39% against. If such a poll were limited to those who actually intended to vote in a referendum, the result would be a decisive 67% vs 27%.

In addition to shifts in Ukrainians’ attitudes towards NATO, the DIF study has looked more deeply at changes in their knowledge about the Alliance. Here, the picture is far more telling. First of all, the majority of respondents admit that they don’t know much. Only about 10.5% of Ukrainians say that they are properly informed about what NATO is. Another 55% say they know a bit, but not enough, while nearly 20% admit that they know next to nothing about the Alliance. An additional 11% say that they are uninterested in knowing more about NATO.

An even more revealing question in the poll was: “How, in your opinion, are decisions made at NATO?” Decisions regarding military operations are approved by consensus, which means that every member has to vote in favor of the issue. The failure to reach consensus is why NATO did not participate in the second Iraq war in 2003, despite considerable pressure from the US. Yet less than 19% of Ukrainians answered this question correctly, a figure that has not improved that much in more than a decade: it was just under 14% in 2007. Another 22% of respondents in the August 2018 poll said that decisions are made by majority vote, while 14% believe that all the rights belong to the “old” members of NATO. By comparison, in 2007, 14% and 17% thought this. Worst of all, nearly half, 45% of Ukrainians, couldn’t answer this question at all.

RELATED ARTICLE: Michael Street: “NATO looks at improving how defense forces from different nations can work together better”

This lack of knowledge of how the Alliance works directly affects attitudes among ordinary Ukrainians. The main reason 47% of those who oppose membership offer both today and in 2007 is that “Ukraine might be forced to join military actions initiated by NATO.” Another 38% think of NATO as an “aggressive, imperialist bloc,” while over 30% say they favor non-bloc status or they are afraid of foreign capital having too much influence in Ukraine. Last year, respondents were given yet another option: “This will provoke Russia to direct military aggression,” a reason favored by 25% of those who oppose membership in NATO. This option has now been removed, since Russia has been engaged in “direct military aggression” against Ukraine more than four years now.

A more in-depth look at the fears Ukrainians express shows that, while they have some regional distinctions, they are similar across different countries. In general, NATO is still associated with war, and not in defense against war. This can be seen in Moldova and Georgia, for instance. Both countries, like Ukraine, have suffered the loss of territory and all three were once part of the USSR. The difference is that Ukraine and Moldova have the same split of supporters and opponents of NATO among their populations, whereas the majority of Georgians support their Government’s efforts to join the Alliance. In a 2017 poll commissioned by the NATO Information Center, 27% of Moldovans opposed to joining NATO said they were afraid that it would lead to conflicts and wars, and that the country would lose its sovereignty, but only 6% worried that it would damage relations with Russia. In the case of Georgia, the main reason of 45% of opponents to NATO in a March 2018 NDI poll was that it would lead to a conflict with Russia. The selection of possible answers varied in all three countries.

In short, attitudes towards NATO in a given country hinge on three factors: a clear position on the part of the Government, the level of knowledge about NATO among the general population, and NATO’s own activeness in the country. In the case of Ukraine, the situation is somewhat unique: NATO’s best advertisement was provided by its biggest opponent, Russia. But unless all three factors are in place, support for the Alliance could disappear as quickly as it appeared.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook