Not too many people will argue against the statement that “Corruption is going on at all levels in Ukraine.” Time and again, news tickers buzz with breaking announcements that yet another bribester has been caught red-handed. Less often comes news that schemes for making money on the side at state enterprises have been uncovered. More rarely yet, come news bulletins that a money-laundering conversion center has been shut down. Hardly a day goes by without news of the latest thieving official trying to make extra money illegally. Even the president once addressed the Verkhovna Rada with a warning that the battle with corruption was the country’s most difficult challenge.

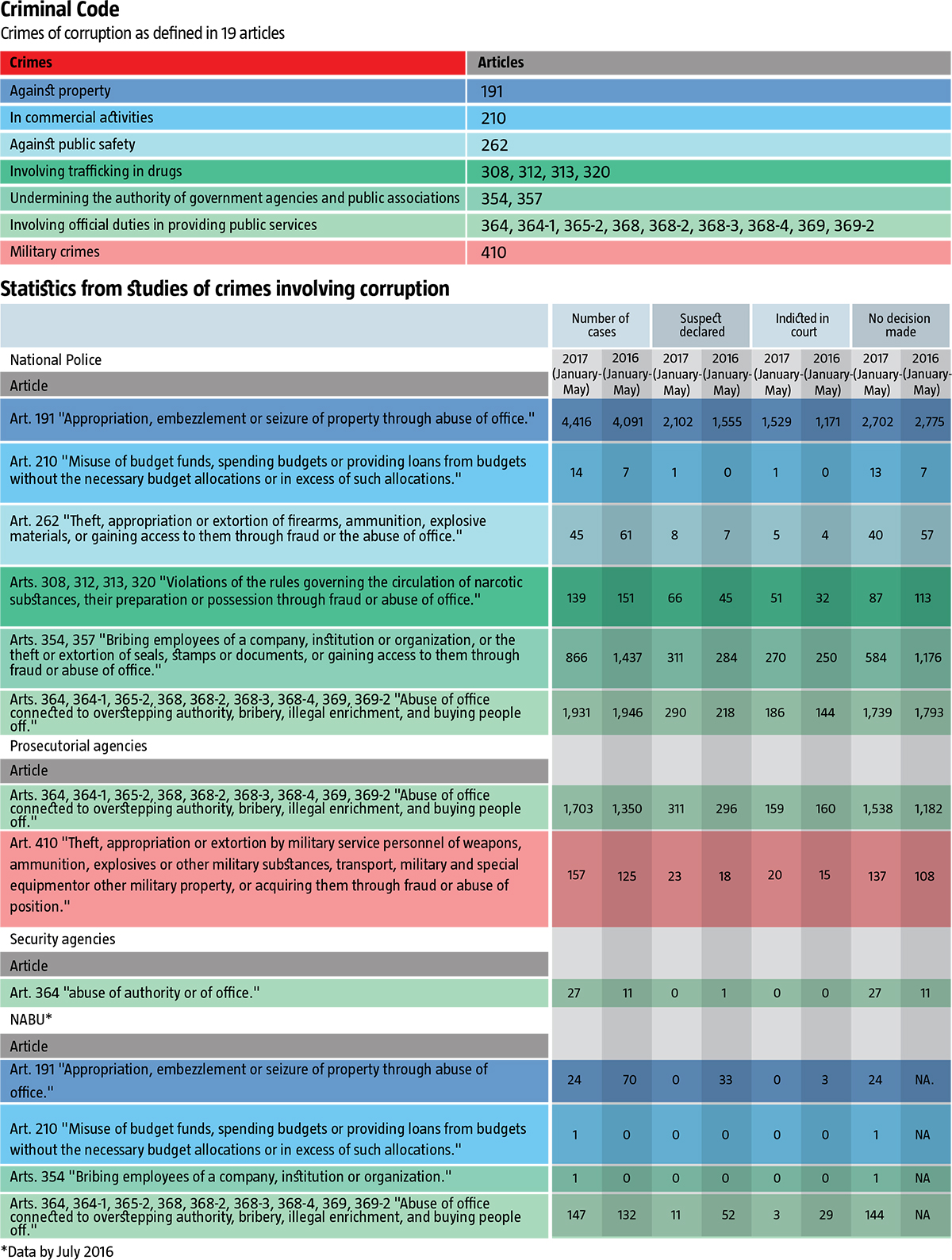

And, in typical Ukrainian fashion, the entire political elite joined the fray. And so, according to official data, law enforcement agencies launched nearly 9,500 cases involving corruption in the first five months of 2017, for crimes that included: misuse of budget funds, fraud, overstepping authority, bribery, and more. During this same period, the court system received over 2,200 new cases. And in the 7,000 cases that judges examined between January and May, not one ended up being ruled in favor of the prosecution.

So, who, in fact, is fighting corruption in Ukraine?

If numbers can be trusted, the National Police have managed to nab the largest number of corrupt individuals: since the beginning of 2017, they have filed 7,400 cases based on evidence of a variety of crimes. Typically, the police arrest those taking bribes from among their own officers, low-ranked government officials, prosecutors and so on. Most of the crimes are connected to taking bribes ranging from a few hundred to thousands of US dollars. In addition to this, the National Police adopted an anti-corruption program whose main aims are to prevent and counter corruption in their own ranks, and to assess corruption risks.

RELATED ARTICLE: Three years of Petro Poroshenko's presidency

The most publicized operation was probably the shocking searches of oblast offices of the one-time Ministry of Revenues and Fees, which were carried out jointly with the Prosecutor General’s Office, which is also keen to report on its battle with corrupt officials. According to PGO data, prosecutorial agencies launched 1,800 corruption cases in the first five months of 2017. In addition to overstepping authority, these included taking possession of weapons or special equipment through fraud, abuse of position, and so on. PGO spokesperson Larysa Sarhan sometimes even refers to the “bribester of the day” in social networks. News disseminated by the agency is dominated by notices that budget funds have been embezzled, taxes have been evaded, and so on. The amounts involved range from a few thousand to tens of thousands of dollars.

In the meantime, the Security Bureau of Ukraine (SBU) is also busy fighting corruption. It sometimes reports about arresting a variety of corrupt individuals among service personnel, police officers, border guards, officials and so on. Still, with only a few dozen cases to its credit since the beginning of the year, the SBU has not actually achieved that much in this area so far.

The National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU), which was set up in the spring of 2015, also hasn’t much to show for itself, number-wise. Its main purpose is to counter corruption among higher officials. It is also responsible for checking on integrity. At this point, the Bureau’s detectives have already arrested possibly the biggest fish in the corruption pond in the history of the country: Roman Nasirov, the former head of the State Fiscal Service; former MP Mykola Martynenko, MP Oleksandr Olyshchenko with his natural gas schemes, and so on. Working together with NABU is the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office (SAPO), which does not have investigative functions but oversees the work of the Bureau. SAPO was set up in September 2015 as part of the PGO, but it considers itself independent of the higher entity.

In terms of investigating corruption among ministers, judges, the premier or president, there should have been an entity such as a State Bureau of Investigation, but it has not yet been set up. Even the competition for the posts of Bureau chief and deputies has remained dragged on for nearly a year now. Given the amount of work necessary to appoint staff to the agency’s regional offices, this process doesn’t look to end any time soon… According to the Criminal Procedural Code, the SBI must be established by November 20, 2017, but it’s clear that it is already way off schedule.

Still, other than law enforcement agencies, Ukraine’s civil society is also engaged in the battle against corruption. One example is the Anti-Corruption Action Center (AntAC), run by Vitaliy Shabunin. The Center tracks procurements at all levels, writes about “political” corruption such as attempts to legally restrict the powers of newly-established anti-corruption agencies, reports on amendments to legislation, and investigates fraudulent schemes. Meanwhile, investigative journalists from various projects have also joined the ranks of those battling corruption and systematically and regularly publish materials dedicated to the latest schemes involving cashing in on public money.

RELATED ARTICLE: Why public sector is the main source of corrupt wealth in Ukraine

Right now, combating corruption seems to have become a trend at contemporary state agencies and politicians behind them. As part of this “anti-corruption trend,” we have seen the story of appointing auditors to audit NABU. In short, the Verkhovna Rada was trying to promote some fairly dubious representatives to this position, which suggests that it really wanted to influence NABU’s work, if not actually take control of it. At the same time, just about every high-profile arrest turns into an excuse for some free PR or anti-PR for various politicians. For instance, the arrest of Nasirov, which was related to the Onyshchenko gas affair, made it possible for NBU and SAPO to remind everyone of their existence. That the public supports NABU is obvious from the hundreds of activists who blocked Nasirov in the courtroom. Certainly this also offered an opportunity to earn political dividends. For instance, members of the Movement of New Forces party were seen in the crowd, a party set up by Mikheil Saakashvili, and they tried in vain to take on the “coordination” of the blocking. Yet Nasirov himself wiped out all the achievements of the law enforcement agencies—or, perhaps more accurately, his wife did when she brought the bail money and he was set free.

The PGO and Ministry of Internal Affairs figured prominently in high-profile corruption cases as well. For instance, at the end of May, the National Police and the Military Prosecutor carried out a massive search operation in the administrations of the former Ministry of Revenues and Fees. The statistics were impressive: 454 searches in 15 oblasts, 23 prosecutors arrested and airlifted by helicopter to the Pechersk District Court in Kyiv, although infamous for the backpedalling of high-profile cases and controversial verdicts in the past. The judge released seven of them on bail, another four on personal recognizance, and the remaining 12 arrested but given the right to also pay bail. The country’s top cop, Arsen Avakov, himself reported on his page in a social network about the achievements of the police: how many were arrested, the total value of the bail bonds, the personal valuables of the arrested that had been seized, and so on. However, unless the court system also does its job, this kind of “report” comes across as little more than self-promotion.

To prevent this kind of situation during the course of judicial reform, anti-corruption courts were supposed to be set up precisely to handle this kind of crime. According to the IMF memorandum from early April, the Verkhovna Rada was supposed to adopt legislation on the anti-corruption courts by mid-June, and the courts themselves were supposed to start working by the end of March 2018. The bill still has not been passed, despite the tight timeframe. What’s more, after the accused bribesters were released on bail, talk once again began about amending the Criminal Procedural Code to make it impossible for suspects to flee.

“You have to understand that the CPC is far stricter about financial crimes than about most other types of criminal activities,” explains one prosecutor. “Your case can collapse simply because the bills the corrupt individual was supposed to take were marked the wrong way. That’s even without talking about bail as an option for the big fish.”

RELATED ARTICLE: Alternative energy in Ukraine: current state, problems and potential

And, of course, the CPC hasn’t been amended. Moreover, the latest initiatives of the Administration in relation to e-declarations give even more cause for concern. So far, the Rada has amended Bill №6172 “On amending Art. 3 of the Law of Ukraine ‘On preventing corruption.’” These changes have expanded the group of individuals who are obliged to file such declarations to include those authorized to carry out state functions or functions at the local level, manages and members of anti-corruption CSOs, and all their subcontractors. For a number of objective reasons, this creates a serious problem, not just for anti-corruption activists, but also for investigative journalists who work through CSOs. Media experts began to describe these changes as an attempt to “put the screws” to anti-corruption activists who were “getting in the way.”

But amendments to the CPC that directly affect NABU are even more dangerous. Two of them are described as “protecting business,” but in reality they curtail the powers of anti-corruption law enforcement agencies by subordinating them to the PGO. One prohibits law enforcement officials, including NABU itself, to investigate a criminal case if that same case was opened and shut based on the same circumstances by another law enforcement agency. The other obligates law enforcement agencies, including NABU, to close a case if it was closed previously based on the same facts. In short, for most of today's officials and MPs, the battle against corruption is clearly not serious but simply a trend, something that they want to add to their resumes. Ultimately, just a new form of sport where participating is more important than actually winning.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook