All of Ukraine’s presidents have one unpleasant thing in common: after three years in power, their personal ratings went into a catastrophic decline. Each of them had his own recipe for success, but three years were enough for voters to get to know them and, accordingly, to become disenchanted. In fact, voters tend to have unrealistic expectations of their presidents, while those running for the post tend to exaggerate their capacity and to promise too much in the hopes of winning. Partly because of this and partly because voters tend to want to see the country’s leader as a kind of Golden Fish that will carry out their individual wishes first, and then everyone else’s, the result is inevitable disappointment.

Not long ago, the latest elected President of Ukraine and Commander-in-Chief of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, Petro Poroshenko, closed the third chapter of his presidential biography. He turned the page as is typical for this genre: ratings way down and a bunch of unfulfilled promises, as well as a few satchels of reasonable achievements. The visa-free regime alone is worth something and theoretically all the setbacks can be written off because of the difficult times, but his predecessors did not have an easy time of it, either.

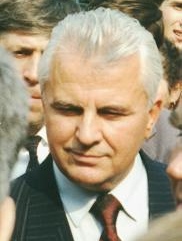

Kravchuk the First

Leonid Kravchuk, the man who found an eternal place in the history of independent Ukraine as its first president, was defeated at the polls before he even made it to three years. Having

won the top post in the land with the support of his one-time communist colleagues and democrats who were thankful for the country’s independence for a solid 61.59% of the vote, Kravchuk probably never expected that fate would give him so little time to rebuild the state. Privatization was just in its early stages and real power was divided among the Verkhovna Rada, which was even able to veto presidential decrees, the president and the Cabinet. Despite the amazing opportunities and prospects that seemed just on the horizon, in less than two and a half years, the situation in the young country had become so much worse that when analysts at the Eastern European Institute in Munich looked closely at the Ukrainian economy in December 1993, they could not understand what was going on and how it was that Ukrainians hadn’t already died of hunger.

won the top post in the land with the support of his one-time communist colleagues and democrats who were thankful for the country’s independence for a solid 61.59% of the vote, Kravchuk probably never expected that fate would give him so little time to rebuild the state. Privatization was just in its early stages and real power was divided among the Verkhovna Rada, which was even able to veto presidential decrees, the president and the Cabinet. Despite the amazing opportunities and prospects that seemed just on the horizon, in less than two and a half years, the situation in the young country had become so much worse that when analysts at the Eastern European Institute in Munich looked closely at the Ukrainian economy in December 1993, they could not understand what was going on and how it was that Ukrainians hadn’t already died of hunger.

As a way to calm down its citizens, who had become impoverished overnight—hardly surprising when pries rose 1,030% in the first year and the pitiful kupono-karbovanets slipped from 740 to the US dollar to 40,000. The Verkhovna Rada was unable to find a better way out of the crisis than to reset the entire government by calling snap elections to the legislature and the presidency. Oddly enough, the situation was somehow stabilized before the vote took place. The Yukhym Zviahilskiy Government had gained unbelievable powers and engaged in any number of cynical measures such as quarterly state budgets, by January 1994 had managed to rein in hyperinflation and by summer industrial output was up more than 4%, a pace that had not been seen prior to that in independent Ukraine—and was not going to be seen again until 2000. However, the miraculous revival had no impact at all on the country’s desperate voters and during the snap election that spring, the Rada turned completely red, stuffed to the gills with communists and socialists.

RELATED ARTICLE: Clan wars: Dnipropetrovsk vs Donetsk in politics of independent Ukraine

Had Kravchuk not behaved like a coy young lady being asked to the dance but immediately declared his candidacy, he might well have been re-elected for a second term. But he himself had no idea what he really wanted and kept saying that he wasn’t going to run because, he said, people were dissatisfied. In the end, in order to prevent a situation where the only frontrunner in the campaign was former PM Leonid Kuchma, a symbol of the country’s hyperinflation and a representative of the red directors and communists who was campaigning on pro-Russian slogans and promised official bilingualism, a heavyweight rival was necessary to support the pro-Ukrainian majority. There were several such candidates, the most promising among them being Speaker Ivan Pliushch. Everything looked set, except that a few days before the deadline for registering nominees, communist-style assemblies of voters from across the country began to press Kravchuk to run, after all, and the old wolf’s heart melted. “If the people want me to run, so be it.”

Needless to say, this scattered the vote and opportunities to use administrative resources but Kravchuk managed to beat Kuchma in the first round, 38.36% to 31.17%. The second round looked like a shoo-in. According to eye-witnesses, however, the evening before Election Day according to estimates, predictions were almost 100% that Kravchuk was a shoo-in. However, a very unpleasant situation took place the next morning. Problems arose with ballot counting in Donbas and all of Donbas had to recount its votes. The result turned into an electoral win for Kuchma.

Kuchma the Big Daddy

Having become the new president, Leonid Kuchma quickly grasped the situation and, using the management style he had polished as director of Pivdenmash, the country’s biggest aerospace plant, began to bring order to the country as he saw it. Positioning himself as a reformer, he presented his program. However, in order to carry out even minimal of reforms, he had to consolidate his relations with the legislature, which was run by the Speaker, Socialist Oleksandr Moroz.

Having become the new president, Leonid Kuchma quickly grasped the situation and, using the management style he had polished as director of Pivdenmash, the country’s biggest aerospace plant, began to bring order to the country as he saw it. Positioning himself as a reformer, he presented his program. However, in order to carry out even minimal of reforms, he had to consolidate his relations with the legislature, which was run by the Speaker, Socialist Oleksandr Moroz.

This proved anything but easy. Kuchma wanted power and a strong executive branch that could “effectively work during a time of growing economic crisis,” while the Verkhovna Rada, naturally, was not prepared to share power with him and began scaremongering about the threat of dictatorship. This confrontation made the resolution of top priority problems in the country a major challenge. Finally, “demonstrating political wisdom,” Kuchma and Moroz signed a constitutional agreement on June 8, 1995, which de facto became a temporary Constitution, recognizing the president as the Head of State and of the executive branch, and granting him the authority to appoint the Cabinet of Ministers, including the Premier.

The first PM appointed by Kuchma was the then acting Premier and a career officer of the Security Services, Yevhen Marchuk. He lasted a year and was dismissed “for working on his own image.” Marchuk was replaced by a strong business executive by the name of Pavlo Lazarenko, who also did not last long. Lazarenko managed to leave quite a mark on the country’s history and on the lives of many later influential politicians, one that can still be seen today. He was a powerful figure, pro-Ukrainian in orientation, and, managing the still-young Yulia Tymoshenko and her company YES’s gas flows from Russia, felt himself quite independent and self-sufficient. Kuchma could sense this and it angered him, but what bothered him most of all was the persistent thought that Lazarenko had ambitions to replace him in the top post. Becoming careless at some point, Lazarenko was declared the country’s top corrupt politician and tossed into the jaws of American justice. This is the point when legendary saga of Ukraine’s battle with corruption began—one that still has not reached a conclusion to this day.

RELATED ARTICLE: What it takes to make change irreversible in Ukraine

This was not the only successful undertaking for Leonid Kuchma. In his first three years, he managed quite a bit. In January 1995, the Rada adopted the Law “On Financial-Industrial Groups (FIGs) in Ukraine,” thanks to which the oligarchic system began to take shape whose fruits Ukrainians are reaping to this today. Kuchma was the key figure in this system and was soon dubbed “daddy.” With the first wave of large-scale privatization in full swing at this time, the FIGs grew stronger and stronger, and Kuchma along with them. Of course, he had to strike a balance between his charges, whose interests did not always coincide, and the international arena, in accordance with his famous “multi-vectoral” approach. It was during Kuchma’s first term that the matrix took shape under which the country would live for the next two decades—and be unable to get rid of, despite two insurrections and a war.

In fact, it’s not entirely true to say that Kuchma’s third year became a critical turning point for him. Yes, there were problems with the Black Sea Fleet and that was when the time-bomb that blew Crimea up in 2014 was first set. His ratings did fall noticeably, but in the absence of a really strong opposition or a comeback by the communists in the Rada, the ever-more statesmanlike Kuchma was sitting pretty. Even the 1998 financial crisis did not stop him from winning the 1999 election, using the formula “the best among a bad lot” by sidelining the more moderate and popular Moroz and leaving only hard-core communist Petro Symonenko to fend off in the second round.

The third year of Kuchma’s second term proved to be the turning point and he entered it completely crushed. First came the cassette scandal connected to the disappearance and murder of journalist Georgiy Gongadze, which grew into the “Ukraine without Kuchma” campaign. Then came the sale of four Kolchuga ESMs, a passive aircraft radiolocation system with an 800 km line-of-sight reach, to Iraq, which was a terrible blow against the Ukrainian president and turned him into a pariah in the west. Even his efforts to warm up relations with NATO and the EU, and to be granted prospects for association and eventually proper membership could do little to turn the situation around. Finally, in 2004, after winning a stand-off with Russia over the island of Tusla in the Kerch Strait in the fall of 2003 that nearly turned into an armed conflict, Kuchma took the provisions on NATO and EU membership out of the country’s Military Doctrine as the ultimate goal of the country’s Euroatlantic and Eurointegration policies, declaring that the country was simply not ready for either at that stage.

But the most far-reaching event during this period, as time would tell, was the appointment of a Donetsk boss, Viktor Yanukovych, to the premiership in November 2002. After the Donetsk clans helped Kuchma become president the first time around, they were given carte blanche to act in their own region. “Do what you want over there, but don’t mess with Kyiv and Kyiv won’t mess with you.” In time, the Donbas appetite inevitably grew and its clans began looking at the capital: we also want to be involved in state affairs. Oddly enough, this coincided with the period when Kuchma himself was ebbing, so when the Donetsk bosses proposed Yanukovych for premier, not without sponsorship from Russia, either, Kuchma agreed.

RELATED ARTICLE: What makes Ukrainians vulnerable to populism

Yushchenko the Dear Friend

The third anniversary of the election of Viktor Yushchenko, who was swept into office on the back of the Orange Maidan, will probably always remain in the country’s history as an example of the most bitter disenchantment with a leader who was the favorite of the entire nation. Perhaps not the entire nation, but no matter how one looks at it, the name Yushchenko was a symbol of hope for change in the country during the Orange Revolution. Whether these hopes were been ill-founded, or the person who was expected to fulfill them was a mere hologram or a political scam is hard to say. One thing that can be said is that the phenomenal prospects and opportunities that came with the victory of the Maidan were wasted by Yushchenko and his team.

of the most bitter disenchantment with a leader who was the favorite of the entire nation. Perhaps not the entire nation, but no matter how one looks at it, the name Yushchenko was a symbol of hope for change in the country during the Orange Revolution. Whether these hopes were been ill-founded, or the person who was expected to fulfill them was a mere hologram or a political scam is hard to say. One thing that can be said is that the phenomenal prospects and opportunities that came with the victory of the Maidan were wasted by Yushchenko and his team.

By his third year in office, Yushchenko was completely lost: his party had lost the VR election to his rival’s Party of the Regions and Yanukovych was once again premier. The return of Tymoshenko to lead the Government only revived all the tiresome squabbles. All that was left was disillusionment and crises. The worldwide economic crisis of 2008, the Russian attack on Georgia as a stern warning, gas wars with Russia. The 2010 presidential election had only two serious contenders, Tymoshenko and Yanukovych, and Yanukovych won.

Yanukovych the Gilt-y Loser

Viktor Yanukovych survived his third year in office with enormous difficulty, and, in fact, that’s where everything ended. Flushed with victory over the “schmucks” who were always in his way in the 2010 election, he enjoyed his presidential prerogatives with such relish that he failed to notice when he had sallied well beyond all acceptable limits.

In 2010, Yanukovych signed an agreement in Kharkiv that extended the term of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet base on Ukrainian territory for another 25 years, to 2042. This and its scandal-ridden ratification later on were the opening chord of the Yanukovych swan song. He went on to use the Constitutional Court to restore the 1996 Constitution, which returned to the presidency the kind of power that Kuchma had enjoyed. Then he played at Eurointegration and being the Great Reformer. But when it came to actually signing the Association Agreement with the European Union, Yanukovych finally showed his true face and went into reverse, carrying out all the instructions coming from his Kremlin mentors. This, of course, led to an outburst of public anger and people went out on the Maidan once again.

In 2010, Yanukovych signed an agreement in Kharkiv that extended the term of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet base on Ukrainian territory for another 25 years, to 2042. This and its scandal-ridden ratification later on were the opening chord of the Yanukovych swan song. He went on to use the Constitutional Court to restore the 1996 Constitution, which returned to the presidency the kind of power that Kuchma had enjoyed. Then he played at Eurointegration and being the Great Reformer. But when it came to actually signing the Association Agreement with the European Union, Yanukovych finally showed his true face and went into reverse, carrying out all the instructions coming from his Kremlin mentors. This, of course, led to an outburst of public anger and people went out on the Maidan once again.

Things might have ended at that, but an unprecedented attack by riot police on students hanging out on the Maidan late at night was the last straw and the country exploded. Once again, Yanukovych was the catalyst for a protest Maidan. This time, however, it was clear this would not be a song-and-dance Maidan, the way it was in 2004. Too much had changed in the intervening years. Unlike the political class, Ukrainian society had been transformed, matured and become braver—and properly learned the recipe for making a Molotov cocktail. Moreover, a new generation of Ukrainians had grown up that was ready to determine its own fate and not beg for small mercies. Every attempt to stop the process, to cut deals, to con people or scare them was doomed. No dictatorial January 16 laws could not stop “an idea whose time had come.”

The end of the three-year presidential term of the twice-jailed Yanukovych, along with his political career, coincided with the start of his career as a migrant. And even then, nothing would have mattered if, having abandoned the country that was careless enough to elect him as president, he hadn’t left behind hundreds of traumatized and killed fellow citizens, a divided society, a completely emptied-out treasury, massive loans, and a letter begging Putin to occupy Ukraine.

Poroshenko the Restorer

Three years into his presidency, Petro Poroshenko still retains his confidence, despite low ratings that hover around the 10% mark. He does have a number of bonuses: the war and the visa-free regime with the EU. And even without these plusses, he is strong enough not to be afraid of anything and to plan his future. Poroshenko in 2017 even has echoes of Kuchma in 1997, when Big Daddy was doing very well. Of course, things are far from perfect with Ukraine’s fifth president, and the third year of office has been a critical one for most of Ukraine’s leaders. The fallen ratings reflect widespread disenchantment as a consequence of not-quite skilled or even inadequate execution of his duties and lost opportunities.

Initially, every incoming president blames his predecessor for leaving behind a poor situation and, for a time, this works. Then comes the phase when saying, “It’s not so easy, things will change, but it takes time” works. Still, after three years in power, those kinds of excuses don’t work, not even from the lips of Petro Poroshenko. Moreover, he lost his kamikaze PM, Arseniy Yatseniuk, behind whose back any number of “interesting” issues were resolved. Now his lightning rod is Volodymyr Groisman. He works pretty well as Prime Minster but not so effectively as the lighting rod given his background of close relations with the president.

Poroshenko is also having trust issues, not just with the Ukrainian voters (which matters less to him), but also with his western partners. It’s becoming harder and harder to cover the feeble progress of reform with attractive gestures or to explain how it’s being actively sabotaged. And this trust means support, money, and much more that he—and the country—needs.

RELATED ARTICLE: Poroshenko vs the memes: How Ukrainian social media users react to the President

It’s still early, however, for Poroshenko to contemplate a well-earned retirement. The lack of a proper, constructive opposition even in the presence of a well-preserved old political guard allows him to seriously dream about a second term. Of course, provided he doesn’t repeat the mistakes of his predecessors, such as Kuchma with his illusory stability in 2002 when Ukrainians were seriously dissatisfied. Or Viktor Yushchenko with his inability to distinguish between enemies and friends, his endless political flirtations, his efforts to cut deals, all of which ended in his defeat and his rival’s comeback.

Stepping into the same puddle over and over again does not take any smarts. Only by considering his own mistakes and those of his predecessors, thoroughly assessing the situation in the country, and genuinely turning to the people who literally spilled their blood so that he might be president, Petro Poroshenko might actually win a second term. But if he relaxes, the risk is always there that he won’t even complete the first one. The grounds for this—and the opportunities—are accumulating day by day.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook