In Soviet Union some dissidents were not worried about being imprisoned or sent to a labor camp. But they would fill with fear at the near opportunity of being recognized mentally impaired and forcefully placed to a psychiatric hospital. While one could still be released and return from a prison or a labour camp, staying in the psychiatric hospitals could be indefinite.

This cruel practice of using psychiatric medicine as a tool to control and isolate dangerous dissidents was formed in the Soviet Union in late 1950s and early 1960s. Khrushchev’s “Thaw”, as it was called, woke up society and scared the authorities. In order to control social activism Soviet government began using the so called “punitive psychiatry”. Chair of the Soviet KGB Yuriy Andropov (1967-1982), played a key role in establishing the practice. In April 1969 he sent a project proposal to the central committee of the communist party, suggesting enlarging and improving an extensive network of psychiatric wards as a mean to “safeguard the interests of the state and society”. In addition to maybe a dozen of ‘special psychiatric wards’ (those were also called ‘prison psychiatric wards’ until 1961), even regular Soviet psychiatric hospitals had separate special units. A simple copy of the court order was enough to admit anyone into psychiatric ward for compulsory treatment (and quite often patients were transferred into psychiatric facilities even without court order). Interestingly enough, there was no legal possibility to appeal such decisions.

Out of dozen psychiatric wards supervised by the Soviet Ministry of Interior, Ukraine had one such facility, which has been located in Dnipropetrovsk since 1968. These facilities have once hosted numerous dissidents, including Leonid Plyushch, Mykola Plakhotnyuk, Anatoliy Lupynis, Volodymyr Klebanov, Yosyp Terelya, Yaroslav Kravchuk and many others.

Soviet general Petro Grygorenko became one the tragically famous victim of the psychiatrists in those days. He was an important figure of the human rights movement as well as a Soviet army general and such dissent authorities tried to explain as insanity. As a result, Grygorenko spent nearly six and a half years in psychiatric wards.

The first psychiatrist, who offered an independent professional opinion on Petro Grygorenko’s court materials, was Kyiv-born Semen Gluzman. He concluded that Grygorenko was sane and healthy and proved that methods of repressive psychiatric medicine were illegal. Soon after, Gluzman was incarcerated himself, spending seven years in labour camps, following by the three years in exile. Despite the fact that Gluzman’s medical conclusion was not official, it was an incredibly important step for the public and the society. Gluzman’s medical verdict was later presented in the West.

KGB demanded that Gluzman refutes his medical conclusion. In one of the letters, sent from the camp, Gluzman wrote: “In September 1973 I was visited by an employee of the central KGB office, Grygoriy Trofymovych Dygas. I was taken to the meeting place ITK-36 in complete secret, where without any witnesses I was questioned and psychologically abused for three days. There was no deal – I declined, but it was very obvious that someone on top needs my help. Say, imagine suddenly Gluzman agrees to dismiss West’s ‘fairy tales’ about Soviet practices of transferring sane people into psychiatric wards. And the price they offered was enormous.”

Compulsive treatment usually caused a vast damage to people’s health. In his autobiographical story, “Carnival of history”, Leonid Plyushch described in a great details his “treatment” in Dnipropetrovsk special psychiatric ward.

RELATED ARTICLE: Nuclear arms in the hands of Russian leaders

“Neuroleptic drugs and daily scenes have broken me morally, intellectually and emotionally. Treatment in psikhushka [1], in my personal experience, was designed in a way to destroy human will and ruin people’s ability to resist. I was trying to spit out the pills, but they have taken away my desire to read or think; first I lost interest in political affairs, then in academic matters, and then eventually I could not even care to think about my wife and children. I had memory loss; my speech became short and disrrupted. All I could think of was smoking and bribes to nurses, who would let me out to the bathroom on one more extra time. I did not even want any of those meetings to see my loved ones, despite the fact that recently it was all I dreamed of. I was afraid that my mental degradation became so visible and incurable, that it would only aid my torturers in their efforts to destroy me. Feeling of hopelessness, indefinite and prolonged stay in this hell forced many sane patients to consider suicide. I have also lost my will to live. But I only kept repeating myself: do not get angry, do not forget, do not give up! ”

Leonid Plyushch is a Ukrainian mathematician and publicist. There is a witness testimony about his court hearings: “The process was held in the empty court room. Defendant’s lawyer was his only representative, and yet he was refused to see the defendant before the hearing. This lawyer only saw him after everything was over. The court has only listened to the witnesses who testified against the defendant. Dyshel, the judge in his case, claimed that since the court considers compulsive medical treatment, it would not need our [witnesses’] additional testimonies, since we are not qualified medical professionals. The most terrifying was the fact, the decision has already been made prior the hearings, and even prior to announcing the results of the medical expertise. Some witnesses were told – ‘he is insane, he is crazy […] he doesn’t even recognises what awaits for him anyway”.

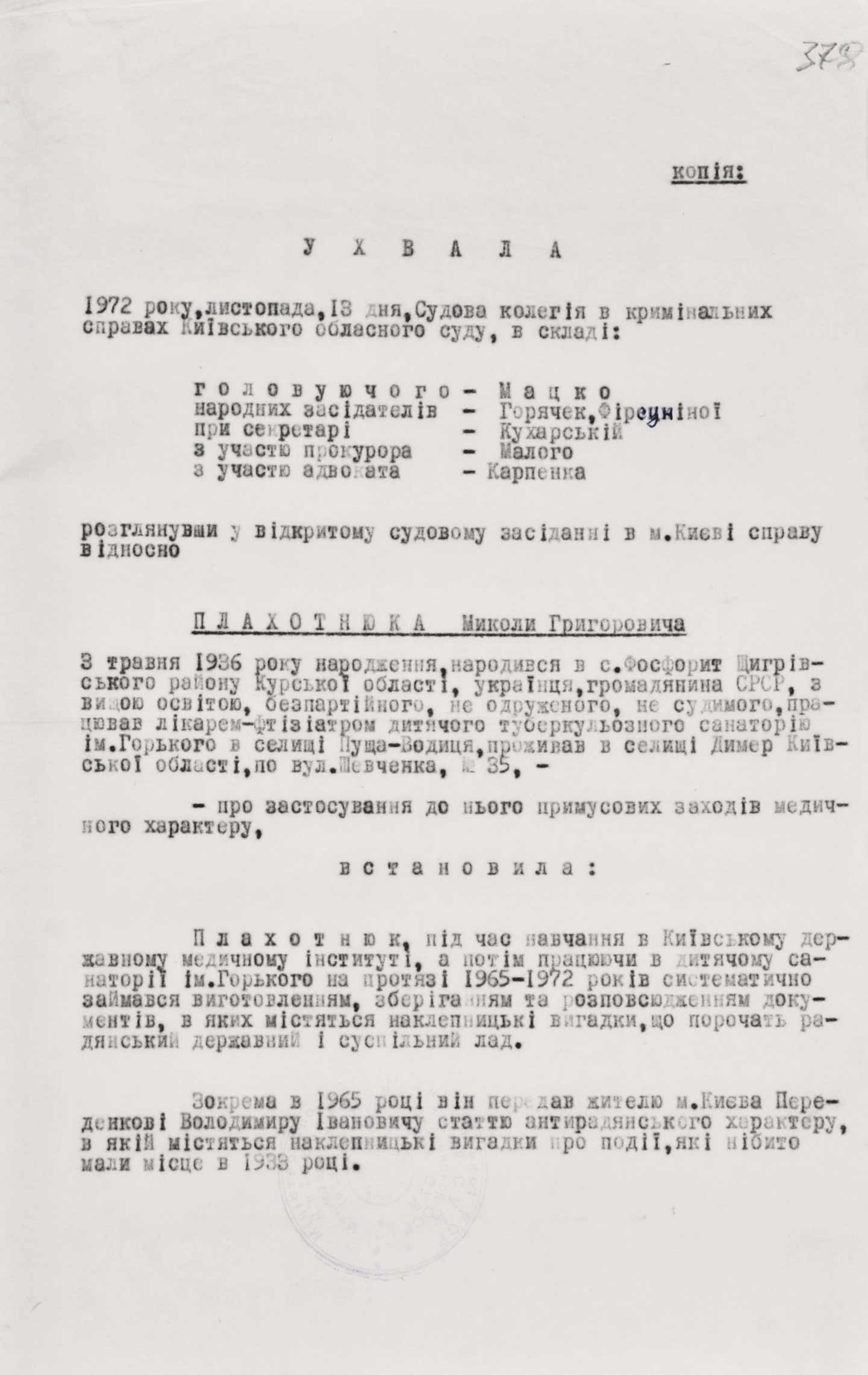

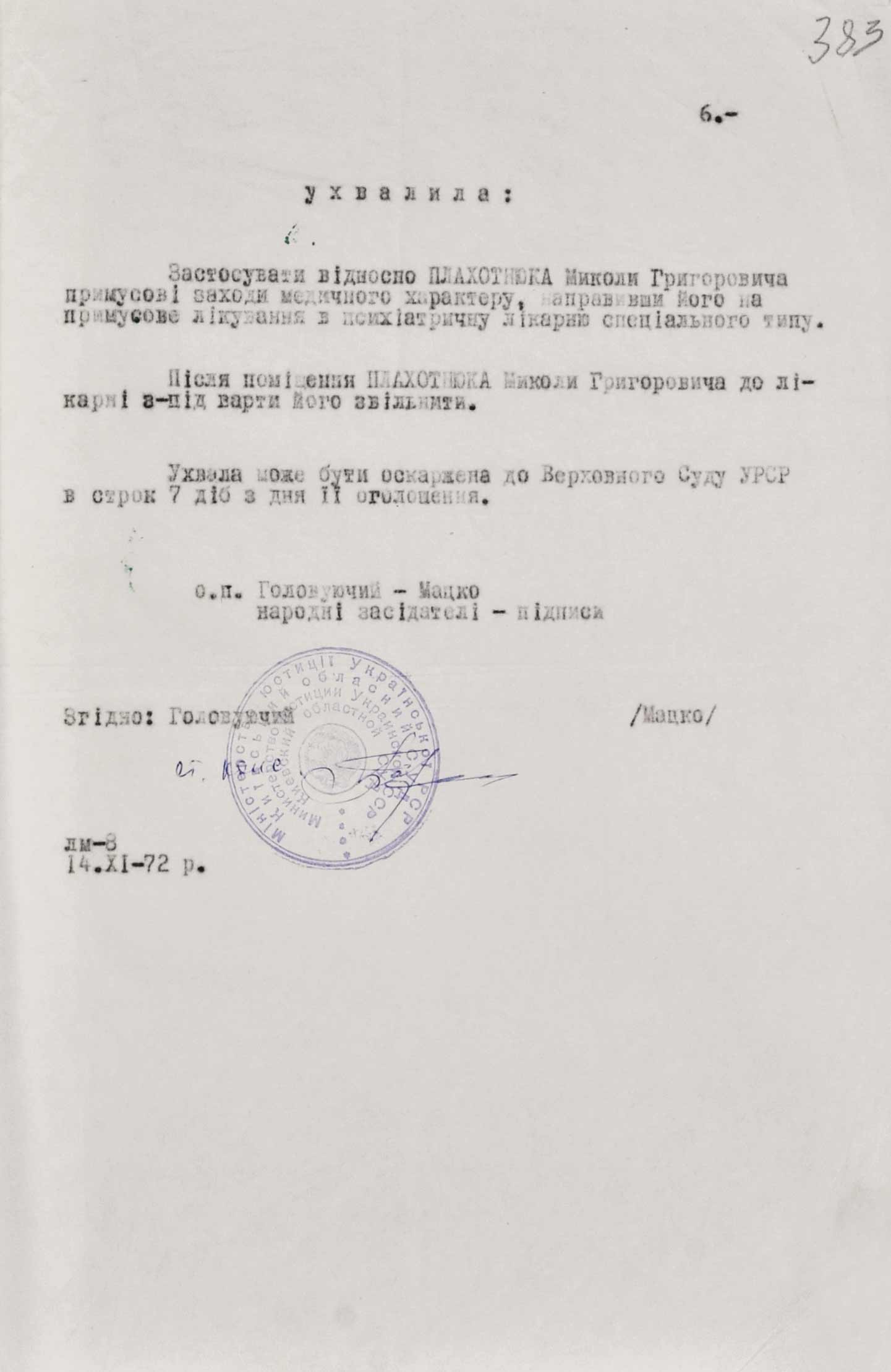

14 November 1972. Kyiv district court’s decision on Mykola Plakhotnyuk case

Human rights activists, including those from Amnesty International, organised protests in support of Leonid Plyushch in London and Paris. Heads of communist parties in France, Britain and Italy demanded his release. Plyush was eventually released and allowed to travel to France, where the western doctors confirmed his mental sanity. Following West’s pressure, Soviet authorities agreed to release the above-mentioned general Petro Grygorenko, as well as a Kharkiv-born psychiatrist Anatoliy Koryagin. Those were a few exceptions among countless victims of the Soviet punitive psychiatry. Some people were transferred to a psychiatric ward for wearing a cross or reading a Bible. The only way out was to acknowledge one’s mental sickness, and even then, according to Plyushch memoirs, only “KGB would diagnose and treat the patient in question, and subsequently decide whether and when he can leave the psychiatric ward premises”.

Mykola Plakhotnyuk, Ukrainian phthisiology specialist, became another victim of Soviet psychiatric machine, spending 12 years behind the hospital bars. He was arrested in 1972 for what was called anti-Soviet propaganda. Kyiv District Court and Institute of Research Psychiatry of V. P. Serbskyy ordered compulsive treatment, which began in Dnipropetrovsk special psychiatric ward, and then Plakhotnyuk was transferred to Kazan. He was then moved to Cherkasy district general psychiatric hospital.

Description, provided by the court medical verdict, is equally eloquent: “Psychological state: the patient behaved exceptionally free and demonstrated a feeling of self-worth and dignity. He explicitly refused to hold a conversation in Russian, affirming that he can only fully express his thoughts in his native Ukrainian and he therefore insisted on having an official translator. When asked about the accusations, he became defensive and aggressive, stating that he had fought and will continue to fight against [Soviet] state injustice towards Ukraine; he repeatedly claimed that Ukraine has to be liberated and its russification is intolerable”.

RELATED ARTICLE: A reform that ruined the Soviet Union

As a result, Plakhotnyuk was diagnosed with “chronic schizophrenia” [2]. Usually, patients of the Soviet psychiatric wards were diagnosed with the so-called ‘sluggish schizophrenia’,[2]as well as querulous paranoia or manic psychosis. Semen Gluzman spoke about these diagnoses: “General-mayor Morozov, director of Institute of Serbskyy and a leading psychiatrist, was holding a lecture, when suddenly one of the court medical experts asked him what sluggish schizophrenia was. Professor Morozov smiled, and replied “You understand, it is when you don’t have hallucinations, you don’t have a mania, but you have schizophrenia”.

Commission for Investigating the Use of Psychiatry as a Political Tool was created on 5 January 1977 as a unit of Moscow Helsinki Group. Kharkiv psychiatrist Koryagin, who partnered with the group, provided independent medical opinion to a number of dissidents. Another volunteer, Yosyp Zisels from Chernivtsi, has a done a routine, but a very important job collecting and passing the information and court materials. One of the first evidence of his criminal investigation (1979) included psychiatric wards’ patients’ files and information leaflets № 8 and № 11. Witnesses confirmed that Zisels was informing them about the crimes committed by the Soviet psychiatric professionals.

Another representative at the Moscow Helsinki Group was the afore-mentioned Petro Grygorenko, while his lawyer, Sofiya Kalistratova, was a consultant in legal matters. In 1977 Grygorenko’s case was made public on the World Psychiatric Association’s congress in Honolulu. The congress passed a resolution recognizing abuse of psychiatric profession in the Soviet Union, created a Committee for Investigation of the Abuse of Psychiatric Practices in the Soviet Union and condemned such abuses. Additionally, on 31 January 1983 Soviet Academic Union of Neuropathologists and Psychiatrists was forced out of the World Psychiatric Association.

By 1988 some 16 specialised psychiatric wards were transferred from the Ministry of Interior of Soviet Union to the Ministry of Health, and later 6 out of them were shut down. 776,000 patients were released. In 1989 the so called ‘anti-soviet propaganda’ and ‘defamation of the Soviet order’ were taken out of the Soviet criminal code. Nevertheless, unfortunately, even nowadays this malpractice and attempts to abuse psychiatry as a tool to manipulate people and their political stance in the territories of the former Soviet Union have not ceased to exist.

Alexander Podrabinek – human rights activist, journalist and one of the founders of the Commission for Investigating the Use of Psychiatry as a Political Tool in 1977. He is the author of the “Punitive Medicine” (1977). Parts of this book were confiscated by the KGB and the rest was published through samvydav [3]. Punitive medicine was written using the sources and evidence which Podrabinek has been collecting during three years, using the evidence of more than 200 victims of the Soviet punitive psychiatry. This book was also presented at the World Psychiatric Association congress in Honolulu and was published in the US in 1980. Owing to the Podrabinek’s efforts, some victims of the specialised psychiatric wards were freed. He himself was also once imprisoned for his activism.

Alexander Podrabinek – human rights activist, journalist and one of the founders of the Commission for Investigating the Use of Psychiatry as a Political Tool in 1977. He is the author of the “Punitive Medicine” (1977). Parts of this book were confiscated by the KGB and the rest was published through samvydav [3]. Punitive medicine was written using the sources and evidence which Podrabinek has been collecting during three years, using the evidence of more than 200 victims of the Soviet punitive psychiatry. This book was also presented at the World Psychiatric Association congress in Honolulu and was published in the US in 1980. Owing to the Podrabinek’s efforts, some victims of the specialised psychiatric wards were freed. He himself was also once imprisoned for his activism.

Alexander Podrabiek: “Punitive psychiatry in the Soviet Union was a universal tool of political persecution and was used against any dissident, regardless of their social, religious or national differences. Every soviet republic had their own psychiatrists who betrayed their profession and agreed to serve the lawless actions of the totalitarian regime”.

Robert Van Voren

Robert Van Voren

Dutch sovietologist, human rights defender, secretary general of the international organisation called “Global war in the psychiatry”, lecture in the universities of Georgia, Lithuania and Ukraine, author of “Cold was in psychiatry”. This book was published in Ukraine in 2017.

During the Soviet times, and especially in 1960s and 1970s, psychiatry was used and abused in every Soviet republic, but in Russia and Ukraine in particular. Psychiatric wards located here were the cruellest. In Dnipropetrovsk many patients were tortured and had medications tested on them. But only after the collapse of the Soviet Union we have realised that it was not only the political prisoners, who suffered, it was also genuinely sick patients. The latter were absolutely destroyed by the system. Over the past 30 years many things have changed, but the legacy of the Soviet psychiatry unfortunately remains. We can only hope that the new generation will overcome these ghosts of the dreadful pasts.

By Liubov Krupnyk

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook

[1] A derogatory term used in Soviet Union to describe psychiatric hosptials.

[2] A term used by soviet medical authorities, also known as slow progressive schizophrenia, characterized by the slowly progressive course.

[3] Samvydav was a form of dissident activities in the countries of the former Eastern Bloc, when prohibited or censored materials were secretly published underground and distributed by hand from reader to reader.