Sometimes it just happens that the essence of a problem really is on the surface. To see it doesn’t require you to bury yourself in details, let alone to be a specialist of some kind. This is particularly true of the choice between the Customs Union (CU) with Russia and the Free Trade Area (FTA) with the European Union. At least that’s what a simple look at the dynamics of exports from Ukraine to the member countries of these two unions would suggest.

SURPRISING NEWS FROM THE EU

The EU dove into the second wave of its crisis back in 2010, but at that point, the problems were strictly financial because they involved the public debt of certain countries and the banks that were holding it. At that point, the EU crisis had little impact on Ukraine, and what impact it did have was very indirect. Ukrainian exports to EU countries continued to recover, albeit slowly.

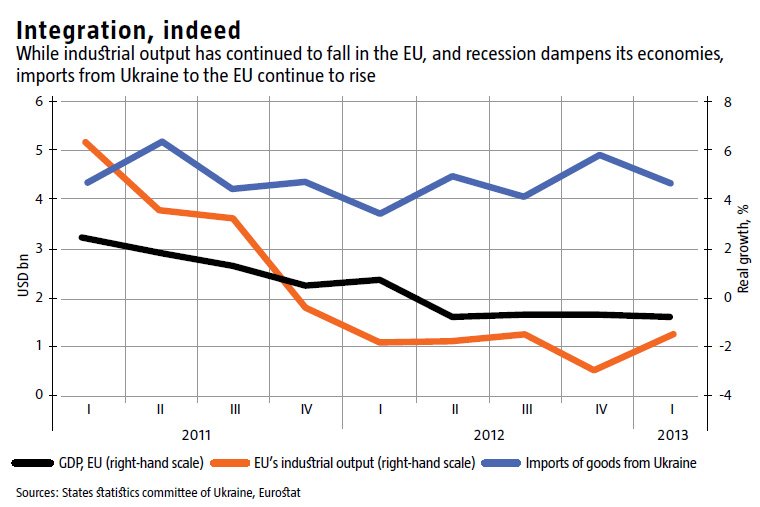

When the trouble in the financial sector began to spread to trade markets and began to cause industrial output to slow down and then to affect the entire economy of a united Europe, demand for Ukrainian commodities began to fall as well (see Integration, indeed). This is in line with the theory that a reduction in business activity led to a reduction in incomes, which in turn caused imports to go down. And Ukraine, as a partner of the European Union, was no exception. By 2012, its exports to EU countries had shrunk by US $900 million or 5%, compared to the previous year, leaving them 10% down from the pre-crisis and early crisis years, 2008-2009.

Still, at the beginning of Q3’03, the situation is looking somewhat different. Although industrial output has continued to fall in the European Union six quarters in a row now, and recession has continued to dampen its economies four quarters in a row, imports from Ukraine to the EU continue to rise for the second quarter. Moreover, the biggest rise can be seen in those countries that are leading in GDP decline in Europe. For instance, in Q1’2013, Ukrainian imports to Greece, Italy and Spain grew 91%, 42% and 8%, while their GDPs declined 5.3%, 2.3% and 2.0%.

READ ALSO: The Mythical Benefits of the Customs Union

This is the most obvious evidence of economic integration that, as it turns out, can even take place during a crisis and does not depend on politics, because it reflects the common interests of the two sides. Indeed, during Q1’2013, total exports of goods from Ukraine to the EU grew 19% compared to the same period of 2012, and services grew 26%. In short, Europeans are importing more and more from Ukraine as money gets tighter for them—without even the need of a signed and sealed Deep Free Trade Agreement. How much more might exports then rise, once the crisis is over?

DIMINISHING PROSPECTS IN RUSSIA

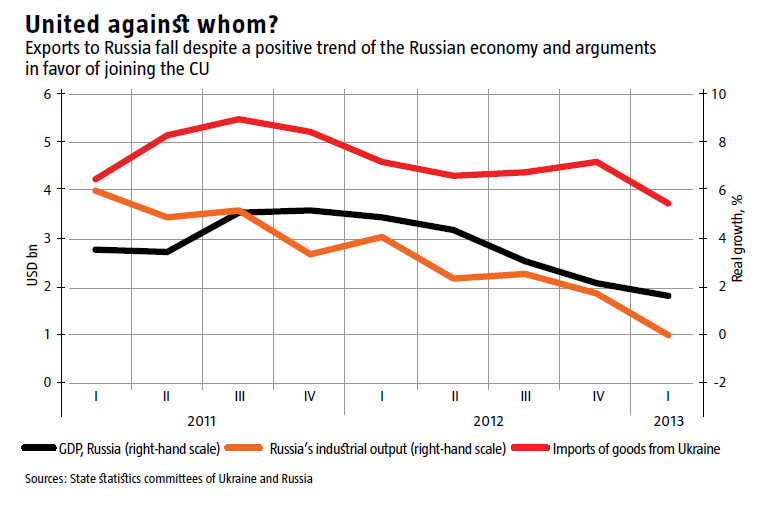

Russia’s economy, where 80% of all Ukrainian exports to the Customs Union go, continued to grow after the crisis of 2008-2009. The benefit to Ukraine was clear: in 2011, exports of goods hit US $19.8bn, which was 26% more than prior to the crisis—and the first time in more than a decade that it surpassed total exports to the EU. At that point, arguments in favor of joining the CU seemed to have the upper edge. Except that last year, exports to Russia fell by US $2.2bn or 11%, although the Russian economy continued to show a positive trend, albeit slower than before (see United against whom?) If the Russian market is saturated with Ukrainian goods, that means the minute Russia goes into recession, then the volume of trade with Ukraine could fall further and faster, something that joining the CU will not help.

The shutdown of the Lysychansk petroleum processing plant in Luhansk Oblast, which processed petroleum for the Russian market, and the Odesa petroleum processing plant idling since 2010 – both originally in Russian ownership (Lukoil recently sold Odesa plant to Kharkiv’s newest tycoon, Serhiy Kurchenko, who is considered part of the Yanukovych Family) reveals a disturbing trend: The Russian government, together with Russian owners of Ukrainian enterprises, can leave 33% of the country’s petroleum processing industry unemployed at the snap of their fingers and is more than happy to do so. This means the fate of Ukrainian exports to the Russian market is very insecure and the prospects for Ukrainian assets in the hands of Russian owners equally so. These two examples clearly demonstrate that Ukrainian commodities do not have a reliable market in Russia, something that joining the CU is unlikely to improve.

Russia long ago chose a policy of setting up as many verticalized production cycles on its own territory as possible. In the last 10-15 years, it has established capacities that allow it to almost entirely satisfy domestic demand for piping, for freight and passenger rail cars, for certain kinds of military hardware, and for heavy machinery for the power engineering sector. Although the quality of the products being manufactured at these new factories is often lower than that produced by their Ukrainian counterparts, domestic buyers in Russia prefer the domestic product on a forced-voluntary basis.

READ ALSO: Thoughts by the Fence

The freight car market offers a clear example of this: at the end of 2012, the share of Russian rail car builders on the CIS market grew, despite declining investment in a restricted market. As a result, Ukrainian exports in the category “railway locomotives” shrank by nearly US $500mn by the end of 2012. Clearly, Russia plans to strategically increase its own economic independence, meaning that Ukrainian exports to that country will continue to see this kind of performance, especially as Russia’s economic cycle slows down.

Another example is the “cheese wars” between Ukraine and Russia, with the latter selectively banning the import of Ukrainian cheeses, ostensibly because of poor quality. Ukraine’s losses from such wars in the overall economic picture are not huge, at about US $87mn in the category “Milk and dairy products, poultry eggs; natural honey” in 2012—although the losses to cheese makers themselves are estimated at around US $300mn. But the very fact that Russia as a state is turning entire branches of the economy of one of its main trading partners upside down shows that politics of the worst kind is a major factor determining the volumes of Ukrainian export on the Russian market. This brings with it overly-high risks for the development of Ukraine’s export industries and makes it strategically pointless to integrate with the Customs Union.

The result of such policies has already led to considerable losses of exports to Russia, and not only in 2012. Exports to Russia continued to fall in Q1’2013 at a growing pace. If industrial growth begins to slow down in Russia, then the problems with the Russian market will become serious for Ukraine’s exporters. Nor will Belarus and Kazakhstan be of any help because their share of CU trade with Ukraine grew only from 16% to 21% in 2012 and remained at this relatively modest level in Q1’2013.

A THIRD WAY IN AFRICA?

While exports of Ukrainian commodities to both the EU and the CU declined in 2012, volumes traded with Africa grew US $2.3bn and completely covered the gaps created in the CU and EU. Not surprisingly, African countries are mostly interested in Ukrainian grains, fats and oils, which overall add up to more than half of their imports from Ukraine.

But that’s not the most interesting point.

Firstly, the expansion of Ukraine’s agro-industrial complex (AIC) has opened the door into Africa, where the potential for selling foodstuffs and raw materials is the greatest. For Ukraine, this is a very strategic direction to expand its foreign trade in. Secondly, Ukrainian companies took good advantage of the Arab Spring in order to enter North African markets in Egypt, Algeria, Libya, Morocco, and Tunis, who are now the country’s main trading partners in Africa. With expanding trade relations, Ukraine was able to move beyond foodstuffs into selling metal products in these countries. This can become the launching pad for deeper cooperation with African markets in other product categories.

READ ALSO: Andriy Pyshnyi:The further Ukraine is from the Customs Union, the better

Seasonal factors caused exports in Q1’2013 to decline 16%, but “have grain, will trade” with the continent. This means that the gradual, steady growth of the farm sector in Ukraine is the only factor necessary for the gateway to Africa to remain open.

In short, Ukrainian business should not get hung up on the DFTA agreement with the EU, which is clearly much more convenient for the development of the country’s economy than joining the more political than economic Customs Union, where Russia intends to keep playing first fiddle. While the numbers clearly show the advantage of European integration over Eurasian integration, the sun does not rise and set in Europe. Diversified markets have always proved to have a positive effect.