For more than a year now, Ukraine has not received any tranches from the International Monetary Fund. Time keeps passing, the country’s need for funding keep growing, and as elections loom, Ukraine’s politicians keep losing their ability, or desire, to meet the inexorable conditions of the country’s main lender. The result is that some are predicting an inevitable crisis, default, and UAH 50 to the dollar, while others talk about the “insatiable monster” that keeps interfering in Ukraine’s internal affairs and exercising “outside influence” over the country. Of course, Ukraine’s political class cannot live without exaggerating reality. But it leads to this question: what really awaits Ukraine if it fails to restore financial relations with the IMF?

RELATED ARTICLE: A looming cash crunch?

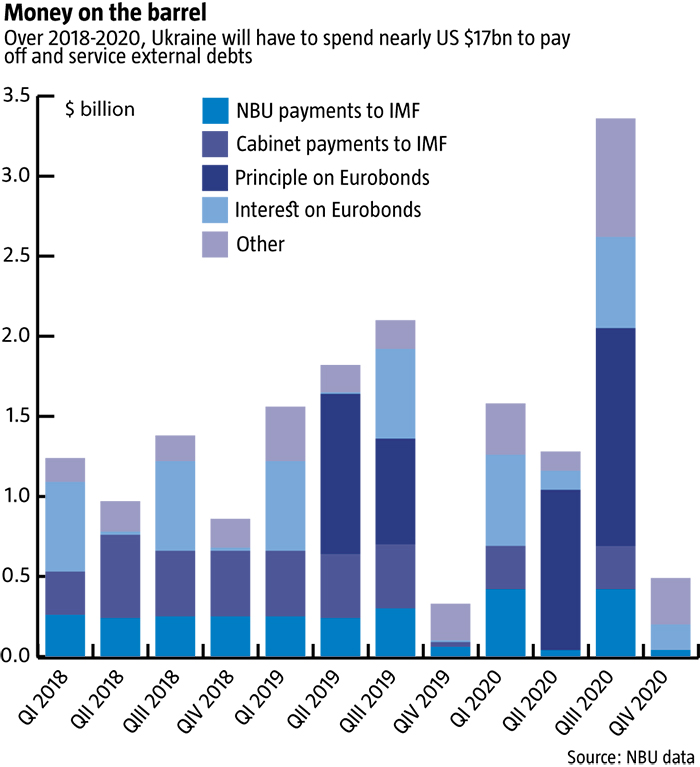

A question of timing

At the moment, the economy appears to be quite steady. GDP and household incomes are on the rise, inflation has finally subsided somewhat, and the currency market is more-or-less stable. If we look no further than today, things don’t look too bad. But if we look a bit further ahead, it becomes immediately clear that the current situation is unlikely to continue for long. According to National Bank of Ukraine estimates, Ukraine has to pay off foreign state loans worth nearly US $17 billion over 2018-2020 (see Money on the Barrel) plus more than US $5bn to service or pay off government-guaranteed loans made to state-owned corporations. The NBU currently has a bit over US $18bn in reserves, meaning that there’s not even to just settle completely with the country’s creditors, never mind making it through this period of high payments without strain. All this quite naturally raises serious concerns.

Still, we have to be aware of this concern, which means looking at the details in depth. The high payout period can be conditionally divided into three sections. The first is prior to the next presidential election slated for March 2019. This is approximately when the current IMF cooperation program ends, which means Ukraine can probably only count on IMF credits during this period, since the launch of a new program is a completely separate matter. According to the NBU, the three quarters that remain in this particular slice will require Ukraine to pay out about US $3.8bn in external government bonds—not a critical amount, but significant. The Bank rightly believes that if Ukraine manages to get two more tranches before the current program ends, there will be no need to refinance external debts prior to the presidential vote.

The second period is between the presidential and Verkhovna Rada votes. Roughly speaking this means QII and III of 2019, during which Ukraine has to pay out over US $3.9bn more. This time will likely be the hardest, as the current IMF program will have ended and there might be no one to sign the next one with at that point, as that will require a functional legislature capable of passing the necessary legislation to meet IMF requirements. The Rada’s functioning is already questionable, even though the political situation is much clearer now than it will be at that point. Moreover, signing a new program will require specific contact persons within the Government to hold talks with the Fund and ensure its fulfillment. In the current Cabinet, Finance Minister Oleksandr Danyliuk was that person. Since his resignation, there has been no appropriate channel for cooperation and no one’s in a hurry to re-establish one, so far. Things could easily continue like this until the next parliamentary election, which means it would be good to have some spare financial strength for this period in the form of substantial gold and currency reserves. That’s, of course, the ideal, while reality is considerably far behind right now.

Now comes the third period, after the VR election, where the rest of the payments come due. At that point, the sums will be far more substantial but they will be coming due at a point when the political situation is more certain. There is good reason to believe that the country will have a completely functional president, parliament and Government by the end of next year. No matter who is in power at that point, the need to pay off country’s debts means that Ukraine will have to agree a new program of cooperation with the IMF.

RELATED ARTICLE: Light at the end of the tunnel

He who hesitates is lost

One or two more tranches before this program ends represent not just US $1-2bn from the IMF for Ukraine but a few million more from other foreign creditors as well. The total amount would not only cover external funding needs prior to the presidential election but also provide a comfortable cushion for the inter-election period. But Ukraine still has to receive this money. Until recently, the main stumbling block was supposedly setting up the Anti-Corruption Court. A few weeks ago, the VR adopted a law that establishes the mechanism for the ACC to exist and any day now MPs are supposed to adopt a bill that launches the actual process of setting it up.

At this point, the second requirement of the IMF comes to the fore: raising household gas rates to market levels. This is where the questions begin to arise. The Government has been talking for quite a few months now that it is in the process of establishing a formula for the new rate for natural gas. However, this formula wasn’t filled with integrals or differential equations that it took so long to write out. So the problem is that the Cabinet keeps trying to come up with as low as a rate as while the IMF, as usual, is relentless in its requirements. It’s not easy to find consensus in this kind of situation.

The problem is that the Government is being stubborn and shortsighted. Obviously, no one wants to raise household gas rates, and along with them residential service rates, just before an election, because it will affect the incumbents’ already-low ratings. The question is what stopped them from doing this half a year or a year ago? The subsidy system for residential utilities protects a very large share of households anyway, and much of the added increase would not really have been noticed. At the same time, the profits it would bring gas extraction companies, especially state-owned Naftogaz Ukrainy and Ukrgasvydobuvannia, which posted nearly UAH 40bn and over UAH 30bn in profits last year, would partly cover additional budget spending to provide larger subsidies. But the Government did not do so, and now, the likelihood that it will do so any time soon, with elections looming, is fading fast.

Nominally at least, these two requirements are pretty much all that the IMF wants from Ukraine in order to issue the next tranche. But there is a third requirement that always remains on the table—a balanced budget. Even there, things aren’t quite what they should be today, because the Treasury reports that for the first five months of 2018, the budget revenue plan was fulfilled 99.4%, but actual spending is somewhat higher than anticipated. As a result, the deficit is currently above the cap established by the IMF.

As the elections draw close, the populism keeps growing, including widespread talk of yet another hike in the minimum wage over 2018 and two more rises to social benefits are already planned for this year. All of this will merely inflate the expenditure side of the budget and could push the deficit well beyond the acceptable IMF norm. Will the Fund close its eyes and give Ukraine the next portion of money simply to support the current Government and its chances of re-election? It doesn’t seem entirely likely.

The long and short of it

If the government ends up not meeting IMF requirements and getting at least one more tranche under the current program, it will have to look for other options. What choices does Ukraine actually have?

The main alternative until recently was funds gained from issuing eurobonds on global capital markets. In September 2017, Ukraine successfully placed 15-year eurobonds with a coupon value of 7.375%. At that time, demand for Ukrainian government papers was far higher than the supply. But less than a year later and the yields on these bonds are already up to 9% and growing. The longer Ukraine fails to get the next IMF tranche, the more foreign investors doubt the government’s ability to service state debts and the less likely the country will be to attract the necessary capital at an appropriately low interest rate. An additional negative factor was the firing of Finance Minister Oleksandr Danyliuk, who announced that all his deputies would be leaving with him, including the person responsible for the 2017 bond placement. If this is so, the Government will lose a working channel linked to world lending markets, contacts with financial advisors, and so on.

Another option is financial resources on the domestic market, although there is little reason for optimism here, too. The main buyers of domestic state bonds or OVDP are the NBU and commercial banks. The National Bank has rejected fiscal domination, meaning financing budget needs by printing money and buying up OVDP in the quantities needed by the Government. If things get really bad, the regulator might soften its position, but right now there is no indication that the Bank is feeling flexible. Meanwhile, commercial banks have been reducing their OVDP portfolios because they need the money for lending, which offers higher interest rates and is currently rising rapidly again. As a result, the volume of OVDPs in circulation is shrinking: from the beginning of the year to mid-June, the stock of hryvnia-denominated state bonds slipped 0.5%, while the stock of hard currency bonds shrank 1.7% in dollar terms. The Government has been issuing new papers in smaller amounts than it is spending to cover old ones. Right now, it’s not even meeting planned financing for the current budget deficit on the domestic market, never mind using such resources to cover the shortfall in external financing.

A final option is raising capital via privatization. Every year, the budget includes billions in planned revenues from the sale of state assets, but every time it ends up bringing in nothing more than a lot of noise. The same is likely to happen this year. Of course, the situation with privatization is better than it was before, because legislation was recently passed to simplify and properly regulate this process. A few weeks ago, the Government also approved a list of assets for large privatization in 2018, then the State Property Fund confirmed it. But the first auction will take place no sooner than in the fourth quarter, when circumstances could be very unfavorable. Moreover, if Ukraine does not restore cooperation with the IMF by then, international investors will have little confidence in this privatization.

Money cycles and black swans

In short, right now it’s very clear that the alternatives to funding from the IMF and other foreign donors are quite illusory because there are no guarantees that Ukraine will be able to draw on the necessary financing from them. Should events unfold in an unfavorable way, the country will have to turn to the NBU’s reserves until the VR elections in 2019. By then, Ukraine will need over US $7.7bn, nearly half of what is in the reserves today.

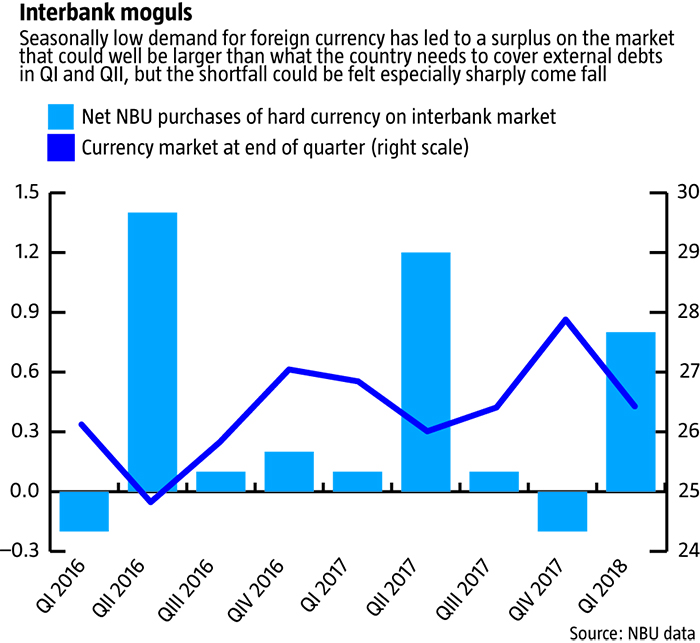

Here, the details matter. Demand for hard currency on the interbank currency market is cyclical (see The Interbank Moguls). In QI-II it tends to be low, so for the last three years, the hryvnia has tended to strengthen during this period and the NBU has been able to substantially top up its reserves. When circumstances are favorable, the sums bought up by the Bank during the first half-year are almost enough to cover external payments. In QIII-IV, on the other hand, there is generally a shortage of hard currency, which tends to push the dollar up and often forces the NBU to sell of part of its reserves. Over the last few years, this dynamic did not grow to threatening proportions, but in 2018 the seasonal shortage of hard currency in the second half of the year will be compounded as the Government buys more of it up. If this happens on the interbank currency exchange, it will lead to a double deficit, which could, in turn sharply push the dollar exchange rate upwards: the dollar has already crept up slightly, although it’s only early July. If the Government buys it directly from the NBU, there will be a noticeable reduction in the reserves that could have a negative impact on the mood among market participants, who will then begin to speculatively hang on to their hard currency. Right now, the Government has less than US $1bn in hard currency on its NBU account. If no money is forthcoming from the IMF, the hryvnia will begin to devaluate quite rapidly and could cross the UAH 30/USD barrier long before the end of the year.

It’s far too soon to talk about UAH 50/USD—certainly in 2018 the chances are almost none. Still, if relations with the IMF don’t get back on track this year, it’s quite likely that at the most critical moment between the presidential and VR elections, closer to the second half of 2019, Ukraine will see a currency rush. Additional pressure will come if the London court agrees that Russia should get back the US $3bn “Yanukovych loan,” a credit Putin gave Ukraine’s then president apparently for not having signed the Ukraine-EU Association Agreement. Looking at things right now, it seems that no matter what, money will have to be returned, but the problem is that this obligation could emerge at the most inappropriate moment. If that happens, it’s entirely possible that by the time the VR election rolls around, Ukraine’s reserves will look a lot like the minimum that they fell to in early 2015, when the dollar spiked. This would set the stage for a fairly serious currency panic.

Let’s talk accountability

And so, it turns out that continuing cooperation with the IMF is the only sure-fire instrument for preventing yet another financial crisis in 2018-2019. Only loans from the IMF and other international donors can guarantee safe refinancing for Ukraine’s external debts over this and next year. All the other options are compromises, often fairly virtual ones at that, that might soften the situation if they worked, but would do little to prevent a crisis.

Under the circumstances, the main issue for the country today is how many people are really aware of the threat. Probably quite a few because the domestic press is abuzz with talk about a possible crunch. To give credit where credit is due, when the Yanukovych Administration abruptly stopped working with the IMF after the first tranche, no one said boo about the fact that this could lead to an economic crisis. On the contrary, all that could be heard then was a chorus about “stability and improvement.” Today, the situation is different, which means the country is changing. There are plenty of people today who are aware of all the risks that the lack of interaction with the IMF represents, although they are still in the minority.

Credit should also go to those who have worked ceaselessly to implement the IMF requirements for the last few years. Over 2014-2017, Ukraine received six tranches worth over US $12.5bn from the Fund within the framework of two programs. There were times when the money was came with some indulgence on the part of the IMF, but in other cases diligent efforts to meet the Fund’s demands made it possible. Altogether, this has been an unprecedented achievement that required enormous organizational, human and, above all, mental effort. It testifies to the fact that Ukraine’s government machine today has plenty of individuals who are prepared to lead the country down the path to a better future. At this point, they are not the ones making key decisions and are not determining state policy in many areas. But Ukraine could get to the point where people like that are in charge. It’s just a matter of time.

One final comparison to the past: previously, every Ukrainian government played a balancing act between eastern and western sources of funding: “If the IMF won’t give it, we’ll take it from Russia.” Of course, there are politicians who will happily propose such an approach again or who will at least bring up how well everybody lived during the times of “stability and improvement.”

Given the nature of Ukraine’s political class and the approaching campaign season, there are considerable doubts that even one tranche will come from the IMF before the current program runs out. By contrast, there are none whatsoever that the dollar will cost UAH 30 in a year’s time. Whether this will be a seasonal spike, after which the hryvnia will once again appreciate in QI 2019, or whether it will become the springboard for a new leap into a massive currency panic should become clear pretty quickly.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook