The past year has been rough on Ukraine’s economy, but it is coming to a happier ending. Shrinking GDP, a nose-diving hryvnia, panic among bank depositors, and uncertain prospects with the payment and servicing of a huge state debt made 2015 no less painful than 2014, but these factors look to be mostly left behind. Macroeconomic stabilization has been reached, making it possible for both the Government and ordinary Ukrainians to more-or-less begin to look ahead with confidence.

Both politicians and economic analysts look towards 2016 with cautious optimism, a mood shared by the IMF. Most forecasters agree that the country’s economy will begin to grow again next year, 2% growth in real GDP being the most common prediction. It’s a modest result, but hopefully things will improve quickly once that level is reached. So far, however, no one is naming the factors behind this growth.

RELATED ARTICLE: “We wouldn’t mind change ourselves”

Over 2014-2015, the economy kept contracting due to domestic problems: a war and an accumulation of economic distortions. In 2016, on the other hand, Ukraine’s economy will face problems due to external factors.

The main challenge for Ukraine will be fluctuating currencies, a trend that is now evident around the world and will continue into 2016. Since the beginning of 2014, the hryvnia fell nearly two thirds in relation to the dollar, going from UAH 8/USD to UAH 25/USD. Most economists consider this unprecedented and say the devaluation of the national currency should boost the competitiveness of Ukrainian goods for some time to come.

In fact, this is not true. In the last 18 months, the dollar has grown 25% relative to a basket of hard currencies. This caused more than one world currency to lose value relative to the greenback, including some of our main trading partners. Last year, Ukraine exported over one billion dollars’ worth of goods to 14 countries, four of them are members of the eurozone. In the 20 months since January 2014, the currencies of these countries have fared thus, relative to the US dollar: the Euro is down 20%, the ruble fell nearly 49%, the zloty fell 22% the Turkish lira fell 26%, the forint 23%, the Belarusian ruble 45%, the Kazakh tenge nearly 45%. Outside Europe and the FSU, the impact has been much milder: the Egyptian pound fell 13%, the rupee 6%, and the yuan only 3%. Only the Saudi rial has maintained its position—for now.

The dollar looks likely to maintain the surge that started in QIV of 2015 into 2016, which means most world currencies will fall even further. If we add to this a rapid and unjustified rise in wages and pensions in Ukraine, the competitiveness of prices for domestic goods on the global market could become as low as it was prior to the current crisis. The implications of this for the economy remains in the memories of ordinary Ukrainians: a deteriorating balance of payments, a new round of devaluation of the hryvnia, problems with the banking system, and so on. Hopefully, the country will manage to prevent another round of macroeconomic turmoil, but the chances of such a hit remain high.

RELATED ARTICLE: Life on the Edge

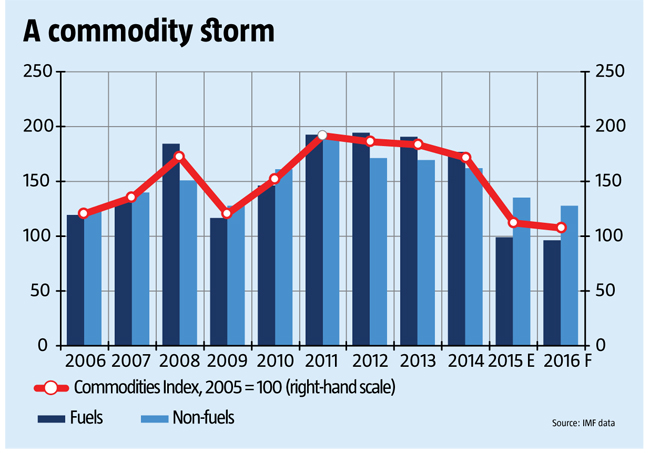

The other challenge for Ukraine’s economy will be global commodity prices. According to IMF estimates, they will continue to slip in 2016 (see graph), though not as sharply as this past year. The good news is that Russian gas will grow cheaper, along with European gas. This should ease Ukraine’s energy problems at least for a time.

But this means that prices will be down for the main types of commodities that Ukraine exports, too. The IMF expects grain prices to go down 6%, which will worsen the financial state of Ukraine’s growers, who had felt relatively good thanks to the devaluation of the hryvnia. Should global prices fall, however, even the current exchange rate will not help many of them, especially those who borrowed hard currency to expand their business. Iron ore prices are expected to fall 20%, which will not only reduce hard currency export earnings in the sector, but will cause pressure on the entire steel industry. Some of its enterprises may well not survive.

In short, the external situation in 2016 could prove exceptionally bad for Ukraine, even with the most optimistic forecasts. If a wave of sovereign defaults in developing countries hits, Ukraine could find itself in a whirlwind global crisis similar to the late 1990s. What’s more, the country cannot expect domestic demand to keep its economy running. The only hope is that reforms will be carried out at a much faster pace in 2016, that this qualitative leap will make Ukraine’s economy far more attractive to global investors and it will grow at a more decent pace.

A commodity storm

|

|

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 E |

2016 F |

|

Commodities Index, 2005 = 100 (right-hand scale) |

121 |

135 |

172 |

121 |

152 |

192 |

186 |

183 |

171 |

112 |

108 |

|

Non-fuels |

123 |

140 |

151 |

127 |

161 |

190 |

171 |

169 |

162 |

135 |

128 |

|

Fuels |

119 |

132 |

184 |

116 |

147 |

193 |

194 |

191 |

177 |

99 |

96 |

Source: IMF data

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook