In Ukraine as in most parts of the world, expectations of growth and of alleviating poverty and unemployment are very often tied to small and medium business. What’s often left in its shadow is the most numerous group of small enterprises, microbusiness. With a few hired hands in addition to the actual owner and monthly sales that are at most in the low five figures in euros, this type of business is very different from other SMEs, the low end of which typically have at least 10 employees and millions or even tens of millions in annual turnover. Yet the social significance and potential socio-economic role, even its role in the socio-political transformation of Ukraine, gives microbusiness a considerable place in the overall scheme of things.

Leaving out occupied Crimea, Ukraine had 1.55 million microbusinesses in 2013, the latest and fullest statistics available from Derzhstat, the government statistics bureau. This category includes physical entities who are entrepreneurs (FOP) with fewer than 10 employees and annual turnover of under EUR 2mn. Small enterprises account for only a few tenths of a percent of all 1.25mn FOPs, while those that qualify as medium enterprises are a few hundredths of a percent. Microbusinesses accounts for nearly 90% of all FOPs. They are equal to 10% of all households in Ukraine. However, the real share of owners of such businesses could well be much smaller, as in some families, one member could be registered as several FOPs or microbusinesses. The average number of individuals working in microbusinesses is 2.5, while in FOPs it’s 1.8. The majority of these are the actual owners who only when necessary—and often unofficially—hire help on a more-or-less permanent basis. It has to be admitted that a major portion of FOPs are actually pseudo-businesses, being only a means to reduce tax liability for those actually employed in most of these enterprises.

Leaving out occupied Crimea, Ukraine had 1.55 million microbusinesses in 2013, the latest and fullest statistics available from Derzhstat, the government statistics bureau. This category includes physical entities who are entrepreneurs (FOP) with fewer than 10 employees and annual turnover of under EUR 2mn. Small enterprises account for only a few tenths of a percent of all 1.25mn FOPs, while those that qualify as medium enterprises are a few hundredths of a percent. Microbusinesses accounts for nearly 90% of all FOPs. They are equal to 10% of all households in Ukraine. However, the real share of owners of such businesses could well be much smaller, as in some families, one member could be registered as several FOPs or microbusinesses. The average number of individuals working in microbusinesses is 2.5, while in FOPs it’s 1.8. The majority of these are the actual owners who only when necessary—and often unofficially—hire help on a more-or-less permanent basis. It has to be admitted that a major portion of FOPs are actually pseudo-businesses, being only a means to reduce tax liability for those actually employed in most of these enterprises.

A separate case is the smallest level of business in the Donbas. In pre-war 2013, Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts had registered 213,000 microbusinesses and FOPs, who together provided jobs for 391,900 residents of the region. Moreover, although the share of microbusinesses providing employment in the commercial sector—25-30% of all those employed and 15-17% of hired workers—was lower than in most other regions in Ukraine, it was at a level higher than in the City of Kyiv and Dnipropetrovsk and Kyiv Oblasts.

But the war radically changed things. It has forced owners of microbusinesses to migrate from the region in large numbers, operations have been shut down, and in some cases businesses have been confiscated and destroyed by the militants. The war has also led to the loss of a major bit of territory and of its entrepreneurs, the overall degradation of socio-economic conditions, and even the physical destruction of assets in the region. All this justifies the analysis of Ukrainian microbusiness without including all of the Donbas.

The socio-economics of microbusiness

In 2013, with the exclusion of Crimea and Donbas (for more convenience, microbusiness data is hereinafter provided with the exclusion of these regions under occupation), Ukraine’s microbusiness employed 2.4mn of the 7.8mn Ukrainians working outside the public sector, budget organizations and banks, and the self-employed. Thus, Ukraine’s smallest enterprises provide nearly 33% of all jobs in the commercial sector outside of banks, and provide work to 20% of hired workers.

Microbusiness accounts for the largest number and share of jobs, 1.5mn and 60%, in the trade and car repair sector. Microbusiness also provides work for 30.5% of those in private healthcare (but only around 30,000 individuals), with medium enterprises taking a larger share, 45.4%.

In manufacturing, transport and farming, some 100,000-200,000 and more are working in microbusinesses, but this accounts for only 7.7% in overall manufacturing and 17.2% in agriculture. Medium enterprises beat these numbers, as do large ones—with the exception of the farm sector—, and small enterprises, with the exception of transport. On the other hand, in agriculture, the share of microbusiness can be expanded considerably by adding in the very widespread family farms, known as personal rural farmsteads (OSH) that are predominantly oriented on produce and have their own farm equipment.

RELATED ARTICLE: Plans of public property management reform and privatization

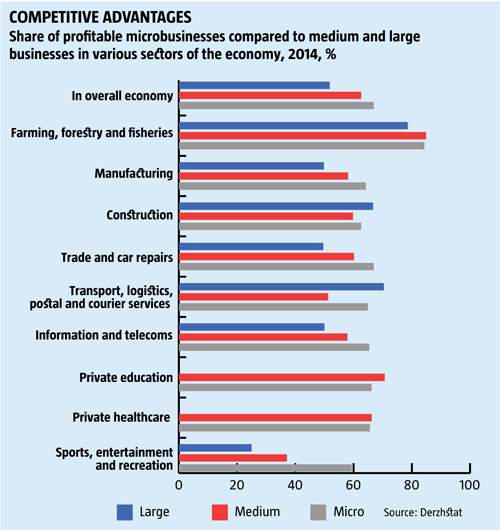

When we look closer at the activities of microbusiness, it becomes clear that in a slew of sectors, it has a relatively larger proportion of profitable enterprises, compared to all the categories of businesses that are larger. In 2014, about 66.9% of micro enterprises were in the black, but among large enterprises, only 51.8% were, and among medium enterprises, only 62.6% showed a profit.

The largest share of profitable microbusinesses was among those in farming, forestry and fisheries at 94.3%, in trade at 66.9%, education at 66.2%, in ICT 65.4%, transport 64.9%, and manufacturing 64.2%. Still, the farm sector has more companies showing a profit among medium enterprises while in transport, large enterprises rule.

By comparison, the most positive results compared to large and medium enterprises could be seen among microbusinesses in trade—66.9% profitable versus 49.6% among large and 60.1% among medium businesses; in sports entertainment and recreation 59.4% profitability versus 25.0% and 37.1%; in ICT 65.4% versus 57.9% and 50.0%. Private education and healthcare also shows a larger share of profitable micro enterprises than medium businesses.

Of course, this could well be largely a result of a more widespread practice of fictitious losses and schemes for transferring profits offshore among large and medium enterprises, as well as among wealthier small enterprises.

A regional breakdown

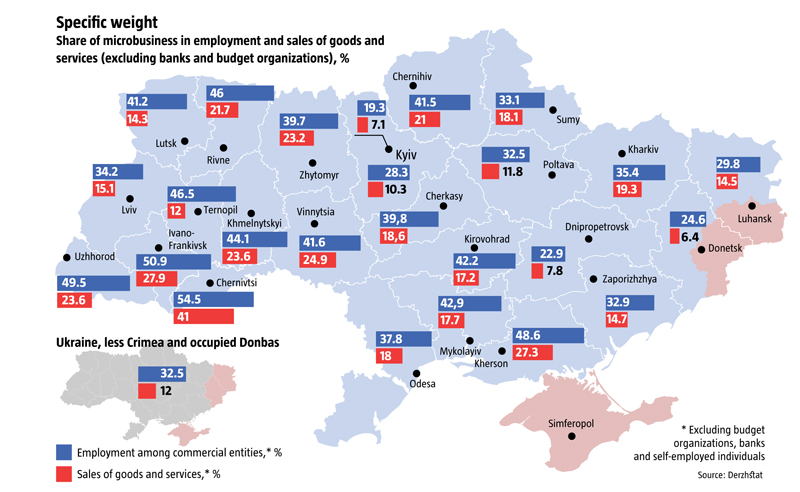

In previous articles, we discussed the “10 employee” coefficient, i.e. the number of employees at enterprises with 10 or more hired workers relative to the number of micro manufacturers, that is FOP and microenterprises with less than 10 hired hands. In general, at that time, this indicator was 4 or less across Ukraine, and the smaller the number of hired individuals, the more petty business-oriented that region. The reverse was also true. The pettiest businesses appear to be in the Carpathian region, which includes Chernivtsi, Zakarpattia and Ivano-Frankivsk Oblasts, and in the south-central region, which includes Kherson and Mykolayiv Oblasts. In these regions, the “10 employee” coefficient ranges from 1.4 in Chernivtsi to 2.2 in Mykolayiv. Most of the other oblasts in Western, Central and Southern Ukraine are within that range, going from 2.3 to 2.7. The lowest coefficient was in Kyiv and Dnipropetrovsk Oblasts.

In this article, we attempt to classify oblasts according to the share of those working in microbusiness among all working residents and the proportion of sales of goods and services in the commercial sector, excluding banks.

The regions with the biggest share of large and medium businesses—the City of Kyiv and Dnipropetrovsk and Kyiv Oblasts—show only 13-18% of all hired workers in the commercial sector working for micro enterprises and FOPs. This is where the lowest share of micro enterprises is involved in selling goods: 7.1% in Kyiv, 7.8% in Dnipropetrovsk and 10.3% in Kyiv Oblasts. Numerically, however, these three regions provide for nearly 40% of all goods and services traded by petty enterprises on a national scale and it is there that the smallest businesses have generated the most jobs for hired hands: 277,900 in Kyiv city and oblast, and 120,700 in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, which is also about 40% nationwide, excluding occupied Donbas, of course.

RELATED ARTICLE: Ukraine's banking sector faces massive consolidation and change of owners

In the 15 oblasts in Central, Southern and Western Ukraine, companies with fewer than 10 hired workers and FOPs—here and further all FOP are included—account for about 40% and more of officially registered workers in the private sector. This indicator is 46.0% in Rivne Oblast, 46.5% in Ternopil, 48.6% in Kherson, 49.5% in Zakarpattia, 50.9% in Ivano-Frankivsk, and 54.5% in Chernivtsi Oblasts. Poltava, Zaporizhzhia, Sumy, Lviv, Kharkiv, and Odesa Oblasts are closer to the national average.

Among others, such indicators suggest that, after decentralization, reasonable tax rates and, more importantly, responsible compliance with tax obligations, especially after payroll deductions, will be crucial elements to the filling of local budgets in most of these oblasts. With the exception of a small group of industrial towns and major interregional centers—Kharkiv, Odesa, Lviv, Kryvyi Rih, Kremenchuk, and Mariupol—large and medium enterprises do not represent enough of a share of employment to compensate for the preferential conditions for microbusinesses.

In terms of sales of goods and services, as well as job creation, microbusinesses represent a smaller share. As noted above, only about 20% of those employed nationwide, with the exclusion of the Donbas, even in those oblasts where micro enterprises and FOP account for nearly 50% of all employment, this indicator is only in the range of 34-37%, that is, in Kherson, Chernivtsi, Zakarpattia and Ivano-Frankivsk Oblasts. The share of microbusinesses in selling goods and services across Ukraine, without the Donbas, is much smaller. The highest rate is 40% in Chernivtsi, and in Ivano-Frankivsk, Kherson and Vinnytsia Oblasts, where they represent 25% or more. Only about 20% of the total volume of sales is due to microbusinesses in Khmelnytsk, Zhytomyr, Zakarpattia and Rivne Oblasts.