On January 18, Aleksandra Ekster, Oleksandra in Ukrainian, turned 135. She is among the top avant-garde artists currently displayed at A Revolutionary Impulse: The Rise of the Russian Avant-Garde at the New York MoMa. The brief bio note by her works says that she is a Russian artist. In fact, she lived three years at most in Russia. Kyiv and Paris were two most important cities in her life. And it was in Kyiv that she lived the longest.

An exquisite intellectual, Oleksandra spoke several languages, travelled the world and socialized with the top artists of her time, including Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Fernand Léger, Guillaume Apollinaire, Ardengo Soffici and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. She was a bridge between Ukrainian and Russian avant-garde and new art of Western Europe. Oleksandra brought Cubo-Futurism to Ukraine, inspired Picasso to use bright colors, reformed approach to scenography and combined avant-garde art with Ukrainian embroidery.

Fundamentals from Kyiv

Оleksandra Oleksandrivna Hryhorovych was born on January 18, 1882, in Białystok of the then Grodno Gubernia, currently in Poland. Her father Oleksandr Hryhorovych was Belarisuan, her mother was Greek. When she was two, her family moved to Smila, a town in Central Ukraine. Her father soon got a job in Kyiv and the city became her home for 35 years. Oleksandra graduated from the St. Olga Women’s Gymnasium, then the class of Mykola Pymonenko at the Kyiv Art College. Her classmates were remarkable futurists, Aleksandr Bohomazov and Oleksandr Arkhypenko. Also, she took private classes at the studio of Serhiy Svitoslavsky. Paradoxically, Pymonenko did not accept new art but all of his students inherited his love for ethnic themes and vibrant colors that are typical in folk art. Ekster was no exception, as well as Bohomazov, Arkhypenko and Malevich who probably attended Pymonenko’s studio as a teenager.

RELATED ARTICLE: Literature in the 1920s' Ukraine

In 1903, Oleksandra married Mykola Ekster, a Kyiv lawyer. From 1905 to 1920, the Eksters lived at Fundukleyivska 27, currently Bohdana Khmelnytskoho Street in downtown Kyiv. They had no children. Oleksandra dedicated all her time to travelling and art. Life in the then provincial Kyiv was not active enough for the energetic and curious budding artist. In 1907, Oleksandra set out on her European tour.

Her first visit to Paris was in 1907. Thanks to Apollinaire, she met Picasso and Braque, and found herself at the heart of the European art scene. Picasso just had his incredibly successful Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Cubism was moving from reflection of reality to abstraction. Oleksandra got carried away with the concept of Cubism; they changed her art radically, though she didn’t dare apply those concepts in her work just yet. Once back in her studio in Kyiv, she spoke about the creative experiments of Picasso and Braque, and all the art folk of town came to listen. Eventually, Ekster turned into a magnet for young artists.

Oleksandra Ekster in Kyiv, 1910

Innovation comes at a price

Kyiv did not have much gallery life in the early 1900s. It mostly featured academic art but did not leave much space for experiment. In that context, the new art show Link arranged by Ekster and Davyd Burliuk at Khreshchatyk in 1908, was a bomb. It was part of the cycle of shows staged in Moscow, St. Petersburg and Kherson, exhibiting works by Oleksandra, Burliuk brothers, Mikhail Larionov, Aristarkh Lentulov and others. However, the provincial taste of the Kyiv audience 110 years back proved resilient. The show was poorly attended, especially that there was an entrance fee. Critics didn’t restrain themselves in foul words and the show ended up with few positive reviews. During the exhibition, Davyd Burliuk was spreading his “Impressionist’s voice in support of art” leaflets. That was one of the earliest manifestos of new art, even if it was a statement of just one artist and not everyone shared the idea. The Link became part of the international history of art but never a meaningful happening in the eyes of the Kyiv public.

RELATED ARTICLE: Kazimir Malevich and Ukrainian Avant-garde

This did not stop Oleksandra from introducing Kyiv to new experiments in art. In 1914, Kyiv saw the show Circle which she opened together with Oleksandr Bohomazov. The debate about new art grew much more active in Kyiv by then (futurist poets met from Moscow and St. Petersburg performer here; futurist poet Mykhail Semenko announced the launch of the Kvero group). But many were still far from understanding and accepting artistic experiment. That’s why the Circle was not popular with the audience and the critics used the opportunity to mock the show. It featured Kyiv-based artists only, including Ekster, Bohomazov and Denysova, as well as members of the art studio at the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute. Apparently the level of works was uneven: some were by beginners and amateur artists. That was one of the reasons for the negative reviews. Still, the innovative value of this approach and the benefits for young artists is hardly a question.

Constructivism in theatre, lighting and body art

Oleksandra won her place in the history of art primarily thanks to her reformist ideas in scenography. She was the first to come up with complex multilayered constructions instead of the typical flat painted decorations, thus filling the entire stage space, not just the floor. Her second innovation in theatre was costumes.

Three shows at the Tairov Chamber Theatre in Moscow, including drama Famira Kifared in 1916, Salomea in 19171 and Romeo and Juliet in 1921, brought her world fame as a reformer in scenography. The way she combined her experience from Cubism, Futurism and Suprematism, with the new plastic drama of the Poltava-born director Oleksand Tairov changed the notion of theatre for good. For various reasons, this tandem did not last, although Oleksandra continued to work on other plays. Art expert Abram Efros referred to her decorations as “the solemn parade of Cubism”. The images created with Oleksandra’s costumes were excessively expressive, passionate, almost extreme and full of the hypnotising power.

A figure with a knife. Costume sketch for the Romeo and Juliet show by Oleksandra Ekster. Director: Oleksandr Tairov. Chamber Theatre, Moscow, 1921

In the early 1920s, Oleksandra worked on costumes for the TV production of Aleksey Tolstoy’s Aelita by director Yakov Protazanov, but her sketches never made it to the screen. The director used his own ideas, though influenced by Oleksandra.

In Kyiv, Ekster created decorations for the ballets by Bronislava Niżyński, sister of Wacław Niżyński, the Kyiv-born star of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Apparently, it was during these shows that Oleksandra began to paint over nude body parts of female dancers. This was the prototype of modern body art. Oleksandra also focused on the lighting as part of the drama action and invited an electric operator to co-stage the shows. Thus light effects and the transformation of a lamp operator into the lighting director appeared in Kyiv.

The Kyiv studio

1918 was crucial for Oleksandra, as well as for many others. She returned to Kyiv for the holidays after the sensational debut of Salomea in Moscow and had to stay here till mid-1920. One reason was the declaration of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, the UNR, the massacre in Kyiv by the Bolshevik General Muravyov, and the subsequent political dramas that unfolded in and around Kyiv at that time. The other reason was that her husband Mykola got seriously ill and never recovered. That kept Oleksandra grounded for some time. Thanks to that break the Kyiv studio of Oleksandra Ekster opened.

She had an innate ability to discover artistic potential in others, reveal talents and open artists. Ekster’s School was not just any traditional art school. It was more of a hub where artists met, communicated and observed the work of masters. Most of Oleksandra’s former students (Vadym Meller, Oleksandr Tyshler, Anatoliy Petrytsky, Oleksandr Khvostenko-Khvostov, Isaak Rabinovych, Klyment Redko, Pavel Chelishchev and others) never managed to shed the Ekster influence. Her Kyiv studio was a place where poets got together. It is thanks to her that Ukrainian Cubo-Futurism appeared. The phenomenon of Ukrainian avant-garde, as it is known today, also began to shape in her studio.

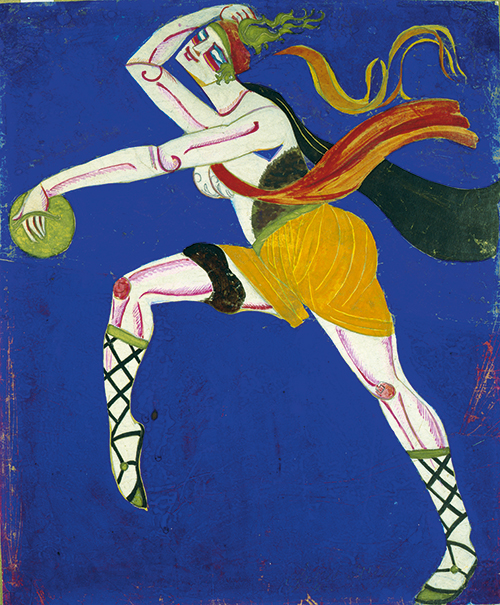

A Spanish dance. Costume sketch by Oleksandra Ekster. Ballet master: Bronislava Niżyński. Bronislava Niżyński’s School of Movement, Kyiv, 1918

In addition to the painting classes, Oleksandra and her students were involved in decorating Kyiv’s streets for the first Bolshevik celebrations. She got to work on Khreshchatyk, the same street where she had previously staged two shows of new art in 1908 and 1914, even if with little success. When asked about the task of contemporary Ukrainian art at the All-Ukrainian Assembly of Art Organizations in June 1918, she said: “We need more free creativity and less provincialism”. Interestingly, this statement is still true for the contemporary Ukrainian art of the current times. Back in 1918, the government of hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky designed a program to develop art in Ukraine. There is no such thing in the modern Ukraine today.

RELATED ARTICLE: Contemporary composer Valentyn Sylvestrov on music art in Ukraine

Ekster’s studio taught both adults and children. She used to say that children are close to avant-garde art thanks to their laconic expression and openness to colors, as well as emotional spontaneity. She would read a fairy tale to the kids, then give them paper, brushes, watercolors, scissors and glue, and asked them to do whatever they pleased. The outcome would often surprise mature artists.

The studio worked until 1919. When the Bolsheviks took over Kyiv, Ekster fled to Odesa and started teaching there.

Embroidered modernity

In the 1910s, educated and wealthy women, including Anastasia Semyhradova, Natalia Davydova, Natalia Yashvil and Varvara Khanenko set up workshops in villages to revive traditional Ukrainian embroidery. They invited Oleksandra Ekster and Yevhenia Prybylska, another artist, to head the workshops in the villages of Verbivka, modern Cherkasy Oblast in Central Ukraine, and Skoptsi (today’s Veselynivka in Kyiv Oblast). The two artists created patterns for embroidery and invited other painters to create designs. Kazimir Malevich replaced Ekster in a while. The embroidered works were displayed successfully in Kyiv, Moscow, Paris, Berlin, Munich and New York. They were used to decorate clothes, handbags, scarves, pillows, belts and more accessories. Folk artists borrowed the dynamics from the avant-garde artists, while the painters borrowed the open and vibrant colors from traditional art.

Maenad. A sketch of the costume for the Famira Kifared drama by Innokentiy Annensky. Costume designer: Oleksandra Ekster. Director: Oleksandr Tairov. Chamber Theatre, Moscow, 1916

In 1915, the exhibition of embroidery in Moscow displayed the first Suprematist works by Kazimir Malevich. Ukrainian women embroidered several works for the famed Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10 in December a few months before it opened.

Ekster was friends with a well-known embroiderer Hanna Sobachko and organized her show in Kyiv in 1918. “Young Slavic nations prefer their native light colors,” she said at the opening of the exhibition. She told the same things to her Parisian friends, Picasso and Braque.

Flamboyant Cubo-Futurism

Ekster followed the concepts of Cubism and Futurism in virtually everything, but color. She could not bear the secondary role of color in such art, while the founders of Cubism and Futurism believed that it was next to none, and used a minimal palette of purely pastel shares and monochrome coloring. It was Ekster who combined the concepts of Cubism with abstract motives and bright colors borrowed from Ukrainian folk art. She inspired Picasso to use vibrant colors in Cubism. Influenced by Ekster, this founder of Cubism expanded his range of colors, using a huge palette and applying contrasts.

Other than the open and vibrant colors, you will not find any other traces of motives or storylines from folk art in Ekster’s works. Like the Paris-based artist Sonia Delaunay (originally from Odesa), Ekster applied the influence of Ukrainian art to her work as a matter of instincts. While Delaunay (as well as Malevich) drew her influences from her childhood memories of a Ukrainian wedding, Ekster made a conscious choice to accept the traces of folk art through interaction and friendship with embroidery artists from the village workshops in Verbivka. Both Delaunay and Ekster are among the founders of Art Deco, a trend in art that combines ornamentalism and bright colors.

The views of France. A Bridge. Sèvres by Oleksandra Ekster, 1914. National Museum of Art collection

The last Paris

In the mid-1920, Ekster left Kyiv for good. She lived in Moscow until 1923 when Anatoliy Lunacharsky, the then Soviet Commissar for Education and the only admirer of avant-garde art in the soviet establishment, asked her to travel to Venice and Paris to prepare exhibitions of soviet art there. After that, she never returned to the Soviet Union.

Life in Paris wasn’t easy for her. She was hoping that Bronislava Niżyński would invite her to stage a ballet show for the Diaghilev company in Paris, or that director Oleksandr Tairov would ask her back to his Chamber Theatre in Moscow. But nothing happened. Oleksandra could not bear to laze around. So she made clothes, decorated ceramic dishware, made puppets and illustrated several copies of Les Livres Manuscrits to mimic old handwritten versions. She was a perfectionist in anything she did.

At the same time, she was teaching at the Fernand Léger's Academy of Modern Art. The students recalled her as a “brilliant teacher, but she irritates people by mentioning Ukraine too often which nobody knows.” Ekster’s Kyiv maid Annushka lived with her in Paris. She brought her Ukrainian clay dishes to Paris and served borshch to their French guests in them.

Ekster’s ties to the Soviet Union broke when the war broke out. She lived her last years alone at Fontenay-aux-Roses in suburban Paris and died in 1949.

Geometry of life

Ekster never had diaries, wrote memories or left letters behind. All her life can be traced through her work: she was always involved in art or teaching. She never had doubts about her personal mission and no life situation affected the quality of her creation. Ekster’s art does not reflect her turbulent life. She seemed to find a shelter from the troubles of life in the stability of painting. Her life reflected a sinusoid: the periods of thriving alternated with the stages of hard work that was hardly visible to an outsider.

Hidden treasures. Three Female Figures by Oleksandra Ekster, 1909-1910. National Museum of Art collection

Unlike other avant-garde artists, Oleksandra did not strive for recognition. All she cared about was to create the best and the most innovative art. That’s why her name did not become widely known in her lifetime. She did not want to be on top of all others. “Ekster courageously followed her fate because she could not betray her nature,” Heorhiy Kovalenko, a researcher of Ekster’s life, wrote.

Reconstruction

In 2008, the National Art Museum held the first retrospect exhibition of Oleksandra Ekster’s works in Ukraine. Over 50 works by Oleksandra displayed at the Museum accompanied by the show of a collection by Ukrainian fashion designer Lilia Pustovit based on Ekster’s art. During her lifetime, Ekster never had a personal exhibition in the Soviet Union, even though most other avant-garde artists were regularly on display in Moscow, Leningrad and Kyiv. Several years ago, art expert Tetiana Kara-Vasylieva organized a reconstruction of embroideries from the two village workshops, including those cased on sketches made by Oleksandra. Today, Avant-garde Embroidery shows are regularly displayed in Kyiv and elsewhere.

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook