Painter Alla Horska would have turned 90 on September 18. She left a distinct trace in the history of the dissident movement in Ukraine. Her tragic death triggered serious outcry. The KGB monitored and recorded information about her death, regularly reporting to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, including its first secretary Petro Shelest. The prosecutor’s office of the Ukrainian SSR had the case under its special control.

Alla Horska was a driver behind the Sixtiers movement in Ukraine and Suchasnyk (The Contemporary) Club for Young Artists in Kyiv. She realized her national identity as an adult, learning the Ukrainian language and throwing a lot of commitment towards the national cultural revival of the 1960s. “You know, I want to write in Ukrainian all the time,” she said in a letter to her father, then director of the Odesa Film Studio, in 1961. “When you speak Ukrainian, you start thinking in Ukrainian. I’m reading Kotsiubynsky. The language is beautiful…” She also had a complaint: “The memories are a huge burden. The memories of the 30s. My heart pounds terribly with the pain of my soul. I want to do something, run somewhere, resent and scream.”

Together with poet Vasyl Symonenko and director Les Taniuk, Horska discovered mass graves of the NKVD victims in Bykivnia, a forest near Kyiv, in 1962. They reported this to the Kyiv City Council, proposing to open a memorial. The Club for Young Artists initiated an investigation. Les Taniuk, Vasyl Symonenko and Alla Horska began to collect information. In 1963, they faced pressure, and Vasyl Symonenko died after he was beaten by the police.

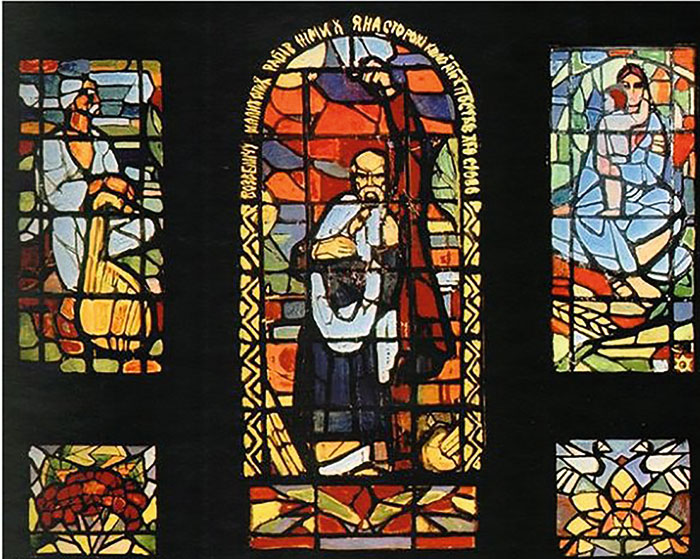

The Stained Glass case

The destruction of the stained glass co-designed by Horska for the 150th anniversary of poet Taras Shevchenko in the hall of the Kyiv National University in 1964 triggered another wave of outcry. It portrayed an infuriated Shevchenko with a woman as a symbol of Mother Ukraine leaning onto him. “I shall magnify those speechless slaves! I will put the words as their guardians!” were Shevchenko’s quotes put on the stained glass. It was demolished immediately after completion as a “piece that is deeply alien to the principles of socialist realism.” Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska, a sixtier, recalled that “The main pogromist was Shvets, the university president. He smashed the ideologically damaging stained glass before the commission even delivered its opinion… Why is Mother Ukraine so sad? What sort of “trial” and “punishment” is Taras calling for? And what is Ukraine doing behind bars?” The Bureau of the Kyiv Oblast Office of the Artists’ Union of Ukraine concluded in its opinion on April 13, 1964, that “The stained glass portrays the image of T. Shevchenko in a brutally distorted way, archaicized as an icon, that has nothing to do with the image of the great revolutionary democrat… The image of Kateryna is in the same icon-like style. It is nothing more than a styled image of the Mother of God… Shevchenko’s words are written in the Church Slavonic language (Cyrillic), which are ideologically dubious when combined with the images interpreted as icons. The images in the stained glass do not even try to show Shevchenko’s soviet worldview. The images created by the artists intentionally lead us into the distant past.”

RELATED ARTICLE: A reform that ruined the Soviet Union

The authors of the stained glass piece were expelled from the Ukrainian SSR Artists’ Union. Some faced a more tragic future: the first post-Stalin wave of repressions hit Ukraine in 1956, hitting artist Opanas Zalyvakha, a co-designer of the piece and Horska’s close friend. He was accused of anti-soviet agitation and sent to high-security prison for five years.

Shevchenko. Mother. Stained glass by Halyna Sevruk, Alla Horska, Opanas Zalyvakha, Halyna Zubchenko and Liudmyla Semykina. 1964

Carnations in court

Alla Horska was a witness in cases of Yaroslav Hevrych, Yevhenia Kuznetsova, Oleksandr Martynenko and Ivan Rusyn arrested for possessing the Ukrainian literature banned in the Soviet Union. When brought to the Kyiv Oblast Court on March 25, 1966, they were surprised to find poet Lina Kostenko, Alla Horska, human rights advocate Nadiya Svitlychna and critic Ivan Dziuba with bouquets of carnations supporting them.

On December 16, 1965, Horska publicly accused law enforcement authorities of psychological pressure on Yaroslav Hevrych during the interrogations, resulting in his false testimony. She used the effective Constitution and laws to prove that it was not a crime to read a book, even if ideologically opposed to the official doctrine. Her persuasiveness was disarming and irritating. She came to attend the trial against dissident Viacheslav Chornovil in Lviv in 1967 with a group of people from Kyiv and signed a letter about the illegal nature of the trial. In 1968, Horska was among 139 academics, writers and artists to sign a letter to the Communist Party Central Committee Secretary General Leonid Brezhnev, Head of the Council of Ministers Aleksei Kosygin and Speaker of the Soviet Union Supreme Council Mykola Pidhornyi. The intellectuals wrote that “the political processes of the recent years have turned into a form of repression against dissidents, a form of stifling civic activity and social criticism that are necessary for the health of any society. They signal an increasingly stronger restoration of Stalinism… In Ukraine, where violations of democracy are amplified and aggravated by distortions in the national issue, the symptoms of Stalinism are even harsher.” The signed letter was sent in April 1968. By the end of April, the authorities were clamping down on the signatories. In July 1968, Horska wrote a public letter to the Literaturna Ukrayina newspaper along with Lina Kostenko, Ivan Dziuba, and writers Yevhen Sverstiuk and Viktor Nekrasov, against a defamation article about the signatories of “letter of the 139”, and against KGB informer Oleksiy Poltoratskyi. She then broke uneasy silence at the subsequent assembly of the Artists’ Union where accusations against all these people were made. She claimed that all the accusations were a lie and forced the presidium to read the text of the protest address. The reading revealed that the letter had no hint at a coup, only polite demand of justice. Horska was once again expelled from the Union for that speech.

This failed to stop the brave woman. In the winter of 1969, she visited Opanas Zalyvakha at the ZhKh-385 area of the Mordovian Concentration Camp. When he was released on August 28, 1970, she co-organized a huge meeting with him at the Kyiv restaurant Natalka. In 1970, she was summoned for interrogation in Ivano-Frankivsk for her support for speeches by historian Valentyn Moroz. She refused to testify.

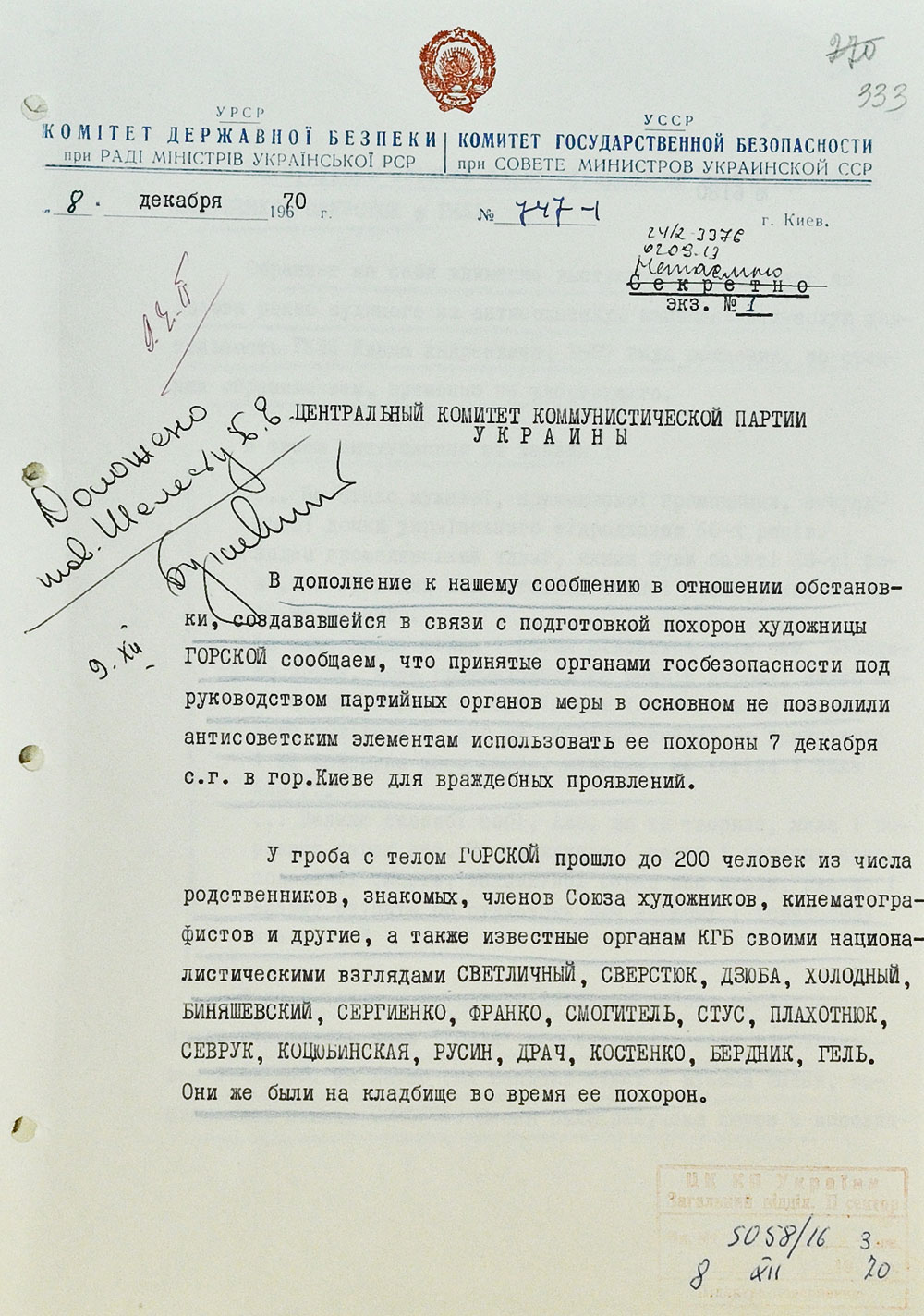

Archives. A special report for the Ukrainian SSR Communist Party Central Committee from Vitaliy Fedorchuk, chief of the KGB in the Ukrainian SSR. 1970

The secret of death

Horska corresponded with political prisoners, including artist Opanas Zalyvakha, and stayed in touch with their families, providing them with moral and material support. Her apartment turned into a place where the returnees from jail would find accommodation and their families gather. She was the epicenter for the intelligentsia and an authority for these artists. Horska was extraordinarily courageous, even if she probably realized how much of a risk she was taking. She faced surveillance and intimidation. Listening equipment was installed in her neighbors’ apartment to monitor her home.

Horska went to visit her father-in-law in Vasylkiv, a small town near Kyiv, on November 28, 1970, never to return again. Her body was found in the basement of her father-in-law Ivan Zaretskyi on December 2, 1970. The Vasylkiv County prosecutor’s office investigated the case initially. On December 7, the case was transferred to Deputy Head of the Investigation Department at the Kyiv Oblast Prosecutor’s Office, advisor to justice V. Viktorov, criminal prosecutor H. Baumstein, and the Kyiv Sviatoshyn prosecutor’s office investigator H. Strashnyi. According to the autopsy report, “A. Horska died as a result of multiple skull fracture with a hemorrhage in the brain cavity.” The examination concluded that the death was caused by “the blunt force trauma with limited impact area”, i.e. a hammer.

Horska’s husband Viktor Zaretskyi was arrested on the day when her body was found under the suspicion of murdering his wife. He faced psychological pressure in interrogations. As a result, he confirmed the official scenario that accused his father, Ivan Zaretskyi, of reasons to kill his daughter-in-law. In the resolution On the Completion of the Criminal Case Accusing I. Zaretskyi Under Art. 94 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR, “based on the testimony of the Horskys’ neighbor and friend H. Zabrodina, O. Horskyi (Alla’s father), and I. Zaretskyi’s letters to his nephew K. Mytsmanenko to Tambov”, the investigators stated that the father-in-law “felt hostile against A. Horska and murdered her on November 28, 1970. He then committed suicide on November 29, 1970.”

That official scenario raised a slew of doubts mostly coming from those who knew Horska closely. One of their claims was that the old and weak Ivan Zaretskyi could not have handled the physically strong Alla, and “no traces of dragging, struggle or self-defense were found on the body and clothing.” Alla’s friends, family and researchers assumed that her death was the work of “the political murder department” reporting to the Soviet leadership.

An unfinished case

The outcry triggered by Horska’s death disturbed the authorities. On December 3, 1970, the Ukrainian Communist Party Central Committee received a letter signed by Vitaliy Fedorchuk, KGB chief in the Ukrainian SSR: “Since A. Horska is known as a figure of authority in the environment of nationalistically-minded elements, they may use her funeral for provocations. We are holding measures to prevent possible unwarranted actions by these people.” That special letter had a hand written resolution by Fedorchuk: “Reported to Comr. Shelest on December 4, 1970.” The Secret Report of the Ukrainian SSR KGB to the CPU Central Committee dated December 5, 1970, noted that “According to the data sent from the KGB under the Ukrainian SSR Council of Ministers, the nationalistically-minded individuals are attempting to use the funeral of Alla Horska for undesired purposes. Because the funeral was postponed to December 7, provocative assumptions and fabrications are spread: Korohodsky, an employee of the Mystetstvo (Art) Publishing House claimed that this was an intentional delay. The KGB does not want the funeral to take place on the Constitution Day so that it does not turn into a political demonstration. Some individuals have proposed a protest at the prosecutor’s office and the city council, demanding that they give back the body. As a result of the measures we have taken, their intentions failed to gain wide support.”

Ivan Franko’s granddaughter Zynovia arranged for the burial at Baikove Cemetery in downtown Kyiv on December 4. But it was eventually rescheduled to December 7 and the Berkovetsky Cemetery in the suburbs. The farewell ceremony took place at the art workshop on Filatov Street. Several hundred people attended.

A December 11, 1970 note to the CPU Central Committee signed by Fedorchuk mentioned that “Mysterious circumstances and reasons of the murder were spoken about at the funeral… Therefore, we believe it advisable to instruct the prosecutor in charge of the case to interrogate Serhiyenko and Hel in order to stop the spreading of provocative rumors around the murder of Horska.” It also mentioned that “poet Lina Kostenko said ‘All this is too ugly to be true’ in her assessment of the involvement of I. Zaretskyi in the murder of Horska.”

RELATED ARTICLE: Punitive psychiatry and its victims

After the funeral, a special note signed by Fedorchuk was sent to the CPU Central Committee on December 18, 1970: “According to the information sent to the State Security Committee at the Ukrainian SSR Council of Ministers, Olena Antoniv, resident of Lviv and the wife of Viacheslav Chornovil known to the KGB for his nationalist sentiments, is commenting on the death of artist Horska in her circle, spreading provocative rumors about the state security agencies allegedly wanting to eliminate those representatives of the intelligentsia who they failed to eliminate in the 60s. According to Antoniv, such actions should be taken by the beginning of the XXIV assembly of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. According to her, this information has reached Ukraine from Moscowites, but she did not mention specific names. Antoniv and her acquaintances are concerned about their future. The KGB under the Ukrainian SSR Council of Ministers is taking actions to identify the sources of the provocative rumors.”

Oleksiy Zaretskyi, Alla’s son, believed that the purpose of the crime had been to intimidate, discredit and demoralize the Ukrainian human rights movement. The murder eliminated the person who provided serious support to the circle of the like-minded. Subsequent repressions, the “great pogrom” of 1972, was probably already in the making by then. The case of Alla Horska was closed. It remains unresolved in spite of the many requests for the prosecutor’s offices of the Ukrainian SSR, the Soviet Union and the independent Ukraine.

Liudmyla Semykina, an associate of Alla Horska, a decorative artist, painter and sixtier, a co-organizer of the Suchasnyk Club for Young Artists. Member of the Artists’ Union of Ukraine (1957; expelled twice, membership restored in 1988): We were romantics, not realists. Alla Horska referred to me as sister, she put her hand on my shoulder when we spoke with our friends. I observed her as a painter, how she holds her hands and her head. Alla was beautiful, brilliantly brought up, intelligent, walking proudly, not a single move without sense. Alla loved art, then she loved herself in art, and she was happy for the people who accomplished something in art. She was poetic and philosophical in her nature, and passionate about national revival that became the sense of her life. Meanwhile, she did not care about comfort in her daily life.

Alla Horska was born for a protest, she was a defender, a torch. She was willing to sacrifice and never afraid to say the truth. I was afraid of her bravery, and I understood the danger. She was courageous, brave, she could break any politicized trial. That’s why she was blacklisted, and then eliminated. The murderer was following her, studying his victim. She was dragged into a trap. There is one assumption shared by Les Taniuk, whereby I was supposed to go with Alla in the car following the one that delivered the sewing machine from Vasylkiv. But I was working on costumes for Zakhar Berkut, the film.

Serhiy Bilokin, PhD in History: The historians researching Ukrainian culture in the 20th century cannot bypass the powerful figures of Vasyl Stus and Alla Horska. They both died. The archives of the Security Bureau of Ukraine (SBU) still store files signed by the ruinous people, such as Vitaliy Fedorchuk. It is all so simple, so straightforward.

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook