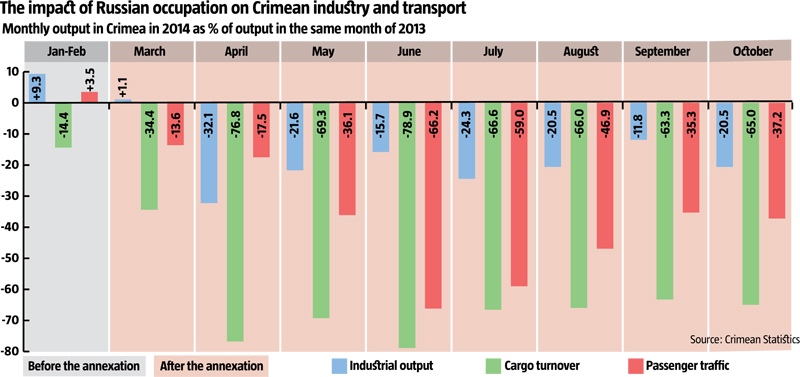

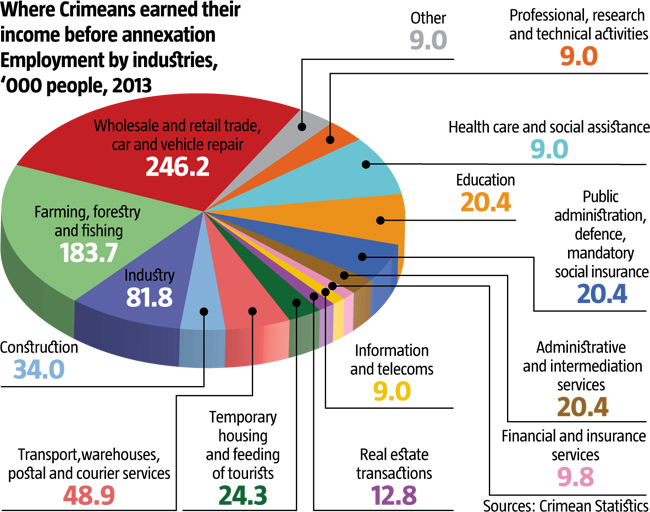

Before Russia occupied Crimea, the peninsula had a robust industry and transport sector that often outpaced similar sectors in Ukraine. The tourists it welcomed, provided services to, fed, and entertained every year outnumbered the local population at least threefold. Obviously, there were things to complain about in how the economy developed, but tourism, ports, transport and trade kept growing. So did the wealth of the locals. As a result, new tourist objects, many of them from small business owners and individual entrepreneurs, were mushrooming. Huge infrastructure projects aimed at shipping goods from deep-sea Crimean ports both to the continental Ukraine and other countries were on the way. This stands in a stark contrast to what is happening in Crimea after the occupation. Most sectors of the local economy have seen a steep decline. Revival, let alone faster development compared to that of 2013, is nowhere near.

The lost market

Food and beverage production used to be Crimea’s major processing industry, and it has been plummeting since summer. It generated 40% of the peninsula’s total output before the occupation. In June-October 2014, its output shrank to 64.3-69% of the level of the same months in 2013. The decline was largely caused by the new barriers in the shipment of Crimean wines and spirits to the continental Ukraine, its biggest market. From March to October 2014, Crimea produced 10.8mn l of spirits, 6.4mn l of cognac and 20.2mn l of wine compared to 38.4mn l, 6.4mn l and 20.2mn l in the same months of 2013, respectively. Wine makers still hope to see some improvement in the access to the Ukrainian market in the future. Otherwise, they will have to cut back on production. Crimean producers of wines and spirits are currently looking for ways to get back on the Ukrainian market by bottling their product in the continental Ukraine. Still, their sales are declining and prospects look dim. The Russian market will hardly offer them a decent alternative since some Crimean producers have already taken their niche while others, mostly the makers of sweetened wines, do not fit Russian qualification standards for wine.

Crimean fishing industry has found itself in a critical situation as well. It has lost the Ukrainian market while finding a niche in the Russian one that always had plenty of fish and seafood will be difficult. Crimean fish producers are struggling to enter it but they are facing serious barriers. The result is a 90% decline in fish catches and sale. Sergey Aksyonov, Crimea’s self-proclaimed premier, has recently admitted that the industry is in a critical condition.

In Q3’14 Crimea’s chemical industry began to decline. Before the occupation, it accounted for 25% of total output of Crimea’s processing industry, and nearly 40% of its exports. Its output in June, July and October 2014 went down to 93.5%, 78.8% and 74.2% of the output generated in the same months of 2013. So far, it has stayed afloat thanks to the lobbied Tax and Customs Control in the Crimean Free Trade Area law passed by the previous parliament of Ukraine (it came into effect on September 27). The law qualifies Crimean chemical products from plants owned by tycoon Dmytro Firtash as “Ukrainian products” and sets forth preferential customs regime for them. This makes the future of Crimea’s chemistry completely dependent on how soon the new parliament decides to amend the law.

International sanctions have caused a steep decline in the shipments of Crimean products to most of their consumers. According to the records of the Crimean customs, Crimea exported goods worth USD 90.67mn in Q2-3’14, which is 3.3 times below its exports over the same period of 2013 (USD 301.9mn; exports to Russia are not accounted for). The structure of exports has changed, too. In April-September 2013, chemicals accounted for 38.1% or USD 161mn. In 2014, their share dropped in price value to 10.3% or USD 9.3mn, giving way to grain at 27.2%, mineral fuels and petroleum products at 29.6%, shipbuilding products at 20.3% and ferrous metallurgy at 9.1%.

Surprisingly, the major markets for Crimea were Switzerland (29%) and Panama (20.4%) in April-September 2014. This signals attempts to use their customs regimes to re-export goods to the EU and the USA that have imposed sanctions on Crimean companies. Still, these efforts will hardly compensate for the huge losses Crimea has suffered from the closure of the European and American markets where it exported USD 79.5mn worth of goods in Q2-3’13. This almost equals Crimea’s total exports in Q2-3’14 (USD 90.7mn). Another new big importer of Crimean goods is Saudi Arabia – it is buying grain.

Turning from a peninsula into an island

Crimea that is part of Russia turns into an island, and this has many negative consequences. It is virtually impossible to deliver anything, including basic consumer goods, to Crimea in winter through any routes that bypass continental Ukraine. Russia admitted that by banning the imports of a number of Ukrainian goods to Crimea in summer and lifting the ban in winter. Equally difficult is the delivery of Crimean goods and commodities in large amounts to Russia. The threefold fall of cargo deliveries through the Crimean territory and the decline of the local seaports confirm that. The Ukrainian government introduced an official ban on foreign ships to enter commercial seaports of Yalta, Kerch, Sevastopol, Feodosia and Yevpatoria as of July 16. Ukraine has also notified the International Marine Organization of the closure of all Crimean seaports for international ships and cruisers. They have transshipped 13.8mn t of cargo over the past year but Ukraine has not felt any effect of the ban. Over January-October 2014, 83.3mn t of cargo passed through the ports under Ukraine’s control, up from 77.5mn t in the same period of 2013. This means that Ukraine has hardly noticed the loss of its Crimean seaports, while the workload of Odesa and Mykolayiv oblasts has increased.

Meanwhile, the seaports in Crimea have virtually stopped. The biggest one in Sevastopol transshipped 0.2mn t of cargo in Q2’14, down from 1.78mn t in Q1’14. Crimean experts believe that all they can expect in the near future is accepting imported goods for Crimea from Russia or other countries that shrug off international sanctions and the prospect of their ships being arrested at Ukraine’s demand.

Crimea’s transport problem could in theory be solved by building a bridge across the Kerch Strait. However, costly and limited in traffic load capacity, it will fail to replace major transport routes running from Crimea to Ukraine. Even if it is built eventually, it will make no sense to deliver goods from Russia to Crimea in order to load them in Crimean ports for further shipment. The neighbouring Krasnodar seaports on the Russian Black Sea coast will be a better option, especially when transit through Crimea could result in sanctions and fines. It is equally unlikely that the Russian authorities will solve Crimea’s electricity and water supply problems. Ukraine supplied 5.96bn kWh of electricity to the peninsula in 2013. Another 1 kWh was produced in Crimea itself. The peninsula would now need USD 450-500mn to import the current amount of Ukrainian electricity at international market prices. Ukraine also delivered nearly 1.2mn cu m of fresh water to Crimea in 2013. Imported even at USD 1 per 1 cu m, it will now cost Crimea an additional USD 1.2bn a year (desalinization of seawater will be equally expensive).

READ ALSO: The Nerve of Annexation

All this puts an unbearable burden on Crimea’s economy which it can hardly endure, especially as markets for its products shrink rapidly. This cost of electricity and water makes it unfeasible to use it for many industrial and farming purposes. As a result, production will shrink or stop. If Ukraine stopped providing fresh water through the North Crimean Canal, it would cause shortages for the population, let alone industry. In November, for instance, Sevastopol began to provide water at specific hours only. This could get worse in 2015.

Current talks of potential construction of alternative energy sources in Crimea are similarly unjustified. First, the peninsula will hardly get enough funding to implement development programmes approved earlier. Second, the generation of current at Crimean plants has dropped as a result of limited supply of electricity from the continental Ukraine from 714mn kWh in March-October 2013 to 498mn kWt in the same period of 2014. Solar and wind power generation has shrank significantly: unlike Ukraine, the fuel-rich Russia is not prepared to subsidize green energy production facilities.

Tourism

Many countries in the world do not produce or export anything but live well on tourism. According to polls, this was the path most Crimeans saw as a priority one in their development before the annexation. The Russian occupation crushed the peninsula’s tourist potential.

According to Oleksandr Liyev, ex-Minister of Tourism in Crimea, almost 4 million Ukrainians, 1.3 million Russians, 250,000 Belarusians and 500,000 tourists from the EU, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and other countries visited Crimea in 2013. The biggest growth of the tourist flow was from the EU and Turkey. In the latest holiday season, only 370,000 Ukrainians visited Crimea. Most of them were IDPs from the Donbas who stayed at the vacant local resorts for free. A mere 1.15 million of Russian tourists came over nine months, which is fewer than last year. This has aggravated internal polarization in Crimea: whereas Sevastopol and the Great Yalta saw some new visitors, Yevpatoria, Feodosia, Great Alushta and Sudak hardly had any clients although they used to be popular destinations and most locals were employed in tourism there.

The growing cost of life and vacations in Crimea, and the lack of convenient transportation routes from Russia to Crimea make it a worse option compared to the Black Sea coast of Krasnodar Krai around Sochi. The Russians are essentially forced to pass that one to get to Crimea through the Kerch Strait. Belarusians find it easier to go to the Sea of Azov or to the rest of the Black Sea coast in Ukraine, while Ukrainian or European tourists will not go to Crimea for obvious reasons. In this situation, Crimea has no chance to revive the 2013 tourist flow of tourists and in the mid-term.

READ ALSO: Crimea: The Multitude of Nations

Prospects

Vladimir Putin has recently signed a law on the development of the Crimean Federal District and FTA in the Crimean Republic and Sevastopol for the next 25 years. The special FTA regime provides for preferential taxation for companies operating in tourism, farming, processing industry, seaports and transport infrastructure, and in IT. However, these decisions will have no serious impact if international sanctions against Crimea stay in place. The new Ukrainian Parliament will most likely cancel the preferential exports law mentioned above (on the creation of the free trade area on the peninsula), thereby cutting ways for the Crimean companies to sell their products to Ukraine or re-export them to the third countries through the Ukrainian territory.

If that happens, the Crimeans and Russians will realize that the peninsula cannot develop successfully without Ukraine. They will also realize that the Soviet government decided to transfer it to Ukraine in 1954 for objective economic and infrastructural reasons, not because Nikita Khrushchev liked Ukraine that much.

Cut off from Ukraine, Crimea will need constant huge funding from the Russian federal budget, even if it turns into a big military base. Meanwhile, Russia’s spending capacity is limited, and so is its motivation to spend a lot of money on what it already grabbed.

Hopes of Crimea’s transformation into a showcase of success of the Russian World look bare: it will now get only RUR 100bn out of 373bn ascribed to it by the target programme to develop Crimea in 2015. The rest of the sum may come in the next years or not come at all. Before the annexation, this amounted to USD 11bn. Now, Crimea will get less than USD 2bn, and even that could plunge as the ruble devaluates and the fiscal crisis in Russia gets worse.