At 33 years old—the same age as independent Ukraine—Zhan Beleniuk has concluded his illustrious athletic career with a bronze medal in wrestling at the Paris Olympics. This marks his third Olympic medal, adding to his two world championship titles. Now, Beleniuk is embarking on a new chapter. As a member of the Ukrainian Parliament, the son of a Rwandan father and a Ukrainian mother is dedicating himself to politics.

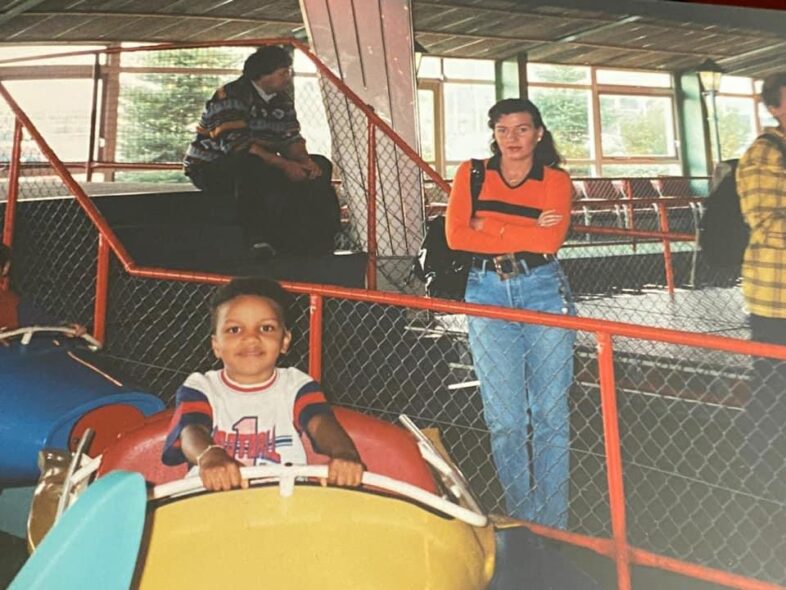

Born in 1991, the year Ukraine gained independence, Zhan is the son of a Rwandan student at Kyiv’s National Aviation Institute and a Ukrainian woman. He never knew his father, Vincent Ndgadjimana, who was called back to Rwanda during the genocide and was killed in an ambush. Zhan grew up in a modest 36-square-meter apartment in Kyiv, raised by his mother, and began wrestling at the age of nine.

Photo: from the athlete’s personal archive

On August 8, 2024, Zhan Beleniuk clinched his third Olympic bronze medal. Following his customary celebration after a significant victory, he performed the hopak, the traditional Ukrainian dance he had mastered during his formative school years. He then placed his wrestling shoes on the mat, marking the end of his career as a professional athlete.

A double world champion (2015 and 2019), triple European champion (2014, 2016, 2019), and triple Olympic medallist, Beleniuk achieved Ukraine’s sole gold medal at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021. Reflecting on his career, he comments, “I’m satisfied with my performances. Perhaps in the future, I’ll feel nostalgic about no longer being an active professional athlete. But I’m happy that my career was successful and that my dreams came true. Trying to prove myself at 37 in the next Olympics would have been difficult, and it was already challenging today.”

At the 2021 Olympics, Beleniuk dislocated his arm just twenty days before the competition. Despite enduring pain and mental strain, and with limited mobility—he could not lift his arm above 90 degrees—he secured a gold medal, fulfilling his “fairy tale.” “The Olympics is a competition where you should never give up,” he asserts. He remains deeply appreciative of his coach, Volodymyr Chatskyh, whose steadfast support was instrumental in his success.

Zhan initially envisioned dedicating himself entirely to his political responsibilities—his parliamentary duties—which he had been balancing with his athletic career since his election in 2019, two years prior. “I took a sports leave, believing it would be final. But the onset of full-scale war shifted the landscape. My loved ones urged me to return to competition, saying: ‘If you feel you have the strength and can still be an effective athlete, bringing glory to your country, then do it.'”

In addition to securing medals, the Ukrainian delegation, comprising 140 athletes across 23 disciplines, undertook a crucial diplomatic mission: to amplify Ukraine’s voice “to aid our country in these challenging times, to reduce the number of Ukrainian casualties in this war, and to defend our territories,” amidst the ongoing Russian narrative.

With his athletic career now concluded, Zhan can focus entirely on his political role. This commitment came at the behest of President Volodymyr Zelensky. At that juncture, Zhan was uncertain of the exact nature of his political role and juggled his duties as a young deputy with his preparation for the Tokyo Olympics. “Then I assembled a team. I realised that if I set aside some personal concerns, I could manage both roles effectively.”

In the 2019 snap parliamentary elections, Zhan Beleniuk was elected to the Ukrainian Parliament on the Servant of the People party list, securing the 10th position behind prominent figures such as former and current Parliament Speakers Dmytro Razumkov and Ruslan Stefanchuk, Ukraine’s first female Prosecutor General Iryna Venedyktova, and the current Minister of Digital Transformation, Mykhailo Fedorov, a fellow newcomer from his generation.

Within Parliament, Zhan engaged with inter-parliamentary groups focused on Japan, the United States, South Africa, Ethiopia, Singapore, and the United Kingdom. He also serves as the First Vice-Chairman of the Youth and Sports Committee. Confronted with the gaps in Ukraine’s sports policy, he notes that these issues have been worsened by the ongoing invasion despite initial progress made under President Volodymyr Zelensky. According to Zhan, Zelensky had begun to mobilise additional resources: “Funds were available, infrastructure was improving, and serious clubs had plans for new facilities, including swimming pools, stadiums, athletic halls, and multipurpose arenas. Many of these projects were inaugurated just before the invasion, and athletes were being celebrated for their successes. This created room for planning.” However, the war has inevitably redirected these priorities.

Going forward, Zhan Beleniuk will confront a formidable challenge: shaping youth and sports policy in a country ravaged by war. “The younger generation, which is leaving for abroad for security and economic reasons and sees it as the future for their children and themselves, represents the foundation of the future Olympic generation. Today, sports infrastructure is in ruins, compounding existing issues in Ukrainian sports: a shortage of coaches to develop young talent, dwindling motivation among trainers and athletes, and insufficient funding. The priority now is to stabilise the situation, so people can envision a future tied to their country and see a place for themselves here.”

In the wake of winning a silver medal in Rio, Zhan faced questions about his loyalty to Ukraine and the allure of pursuing opportunities in countries offering better sports prospects. Zhan affirmed his commitment to Ukraine and expressed a desire to drive change: “I began achieving significant results at a time of national crisis. My first major success came in 2014—amid the Revolution of Dignity, Yanukovych’s flight, and the annexation of Crimea. Such political turmoil could not have been conducive to sports development. However, over time, the situation improved. I noticed growing support from patrons and sponsors, and the state began to allocate additional resources to enhance the conditions for ordinary athletes.”

Zhan Beleniuk had to remind Kyiv’s mayor, Vitali Klitschko—another former world boxing champion—to honour his pledge to award him an apartment in Kyiv for his gold medal performance in Tokyo.

Zhan’s Ukrainian identity is a source of great pride. He reacted strongly when the International Wrestling Federation’s press office erroneously listed him as Russian, retorting with a resolute “I am Ukrainian!” and sharing a photo of his match with the inscription on his back framed by a heart. Yet, being both Ukrainian and Black positions him as a distinctive figure. “If an ordinary person sees me [in Ukraine], they will likely think I’m not Ukrainian. Wouldn’t you agree? In France, there is a more visible presence of people of colour, but the situation remains different in Ukraine. Ukrainians typically encounter Black individuals who are students or businesspeople, but few imagine that a Black person can also be Ukrainian. But it’s a matter of time. As the number of migrants increases and more mixed-race individuals from intermarriages appear, perceptions will evolve.” Zhan notes a sense of solidarity among mixed-race individuals. For instance, Dzhoan Feybi Bezhura, with a Ugandan father and a Ukrainian mother, represented Ukraine in fencing at the Paris Olympics.

Zhan visited Rwanda twice, forging connections with his Hutu father’s family and immersing himself in the country’s tragic history to better understand his roots. After spending two months there, he solidified his identity as Ukrainian: “I was born in Ukraine, I grew up here, and this country has profoundly shaped me. The circumstances and environment that shape you define who you are. Mentally, I am unequivocally Ukrainian. Even if I might appear Afro-Ukrainian or even African, I am nonetheless a product of Ukrainian civilisation, or however you wish to describe it.”

On February 24, like many Kyiv residents, Zhan was blindsided by the onset of what would become a large-scale war. The following day, he evacuated his mother from Bilohorodka, near Bucha, to Khmelnytskyi and, alongside friends, threw himself into volunteer work supporting the military supply chain. He was among the first to enter the liberated town of Irpin on April 1, where he encountered the grim aftermath of the conflict, including the bodies of soldiers and civilians.

“People were just emerging from shelters, bewildered and frightened by the chaos. The war has revealed people’s true natures—both their noblest and basest aspects. It is a catalyst that exposes who is who. Although I am trained as a psychologist, I am not a practitioner, so I found myself compelled to analyse the situation.”

To wrap up, I asked Zhan whether he believes Ukraine will prevail in the war.

“We are doing everything within our power to achieve victory,” he asserts. “I am confident. Although I cannot specify the exact terms for peace just yet, I expect a compromise will be necessary. Should Russia be defeated, it will be on Ukraine’s terms, which would involve normalising the situation, economic recovery, and securing strong security guarantees. We must not only protect ourselves but also safeguard the broader civilised world.”

Reflecting on his approach to preparation, Zhan recently told Ukurier: “I didn’t dwell too much on the future. Each night, I would tell myself: tomorrow will be challenging, I need to fight and win. The following day, I can rest. This approach proved effective.” He hopes that this resilient mindset will also help Ukrainians endure the current crisis and ultimately emerge victorious.

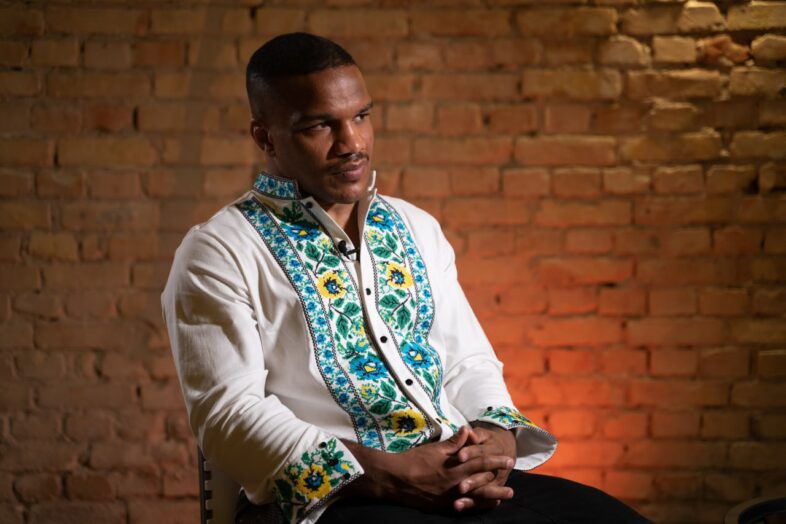

Photo: The town of Bucha after the Russian occupation