Why is Ukraine so poor? That’s not an easy question to answer. If we listen to its politicians and officials, there’s an impression that the country has everything it needs in order to succeed. Fertile soil, hard-working and skilled people whose qualities are often praised by employers in Poland, Czechia, Spain and Italy, and high intellectual abilities that regularly bring home medals from international competitions for public and post-secondary students. Ukrainians even have a knack for business, to judge by statistics—the share of entrepreneurs is not that different from other countries—and practice—whenever there’s a crisis, it takes considerable entrepreneurship not to end up bankrupt. In short, the country’s potential is enormous.

But just take a look in people’s pockets, or even just at official statistics, and it’s obvious that something is wrong. Otherwise this potential would not remain so untapped. What’s missing? At first glance, two things come to mind. Firstly, a system of social relations that is people-friendly and oriented towards human development. The system that Ukrainians inherited from the USSR—and are having such a hard time transforming—has never really worked to develop human potential. Secondly, spirit. Because weakness of spirit, cowardice, is the main reason why people remain ignorant and corruptible, why they lust after easy money and prefer to shift their burdens onto others—especially the state.

These two fatal flaws form a vicious cycle: the inadequate system produces weak-spirited individuals, and weak-spirited people don’t have what it takes to push the system in a better direction. And so every attempt at reform turns into a bitter struggle between bright, distant possibilities and a gloomy reality. The tragedy is that the latter too often wins out.

The right management model

Reforms in the way that state enterprises or DP in Ukrainian are managed are hardly an exception. Why aren’t these reforms brought to their logical conclusion? It’s not for want of ideas and useful models to follow. World practice offers more than enough examples of how to properly manage state-owned companies.

Let’s start with the management system. There are three types of models in the world for executive management of public corporations: decentralized or sector-oriented management; a dual system where the company is managed by a sectoral body and a coordinating body that governs all sectors; and centralized management. Most countries understand that the centralized model is the best one and some have been switching their systems to it. But in Ukraine, not all of those in power have come to the same conclusion. Not only is the system decentralized, but it is even somewhat anarchic: according to the State Property Fund (SPF), the country has 155 properties currently under state management, of which at least 60 are being managed by state enterprises. This isn’t a model, but simply a collection of leftovers from the collapse of the soviet system of administration.

Flawed as this model is, the bigger problem is that politicians regard different government agencies based on the value of the assets of subordinated state companies. In other words, the bigger the assets, the more “substantial” the government agency and the more there is to steal. And the “substance” of various ministries and agencies becomes the focus of political horsetrading when portfolios are being handed out.

RELATED ARTICLE: Why public sector is the main source of corrupt wealth in Ukraine

The logic of it is simple: today, Ukraine’s state enterprises “feed” thousands of government employees, so that if they are moved under the umbrella of a single holding company, the number of parasites will go down by several factors and the scale of waste and inefficiency will fall immediately. This argument can be augmented by many deeper ones, including the fact that the centralized model makes it easier to separate the commercial, regulatory and social functions of state enterprises, to coordinate the operation of various assets more quickly and more focused on a core activity defined in state policy, and so on.

Most constructive arguments favor setting up a single holding company to manage all state enterprises. Still, when it comes down to it, months have passed and still some power utility hasn’t been handed over to the SPF or a major production is made of the transfer of UkrZaliznytsia, the state railway company, from the Infrastructure Ministry to the Cabinet of Ministers.

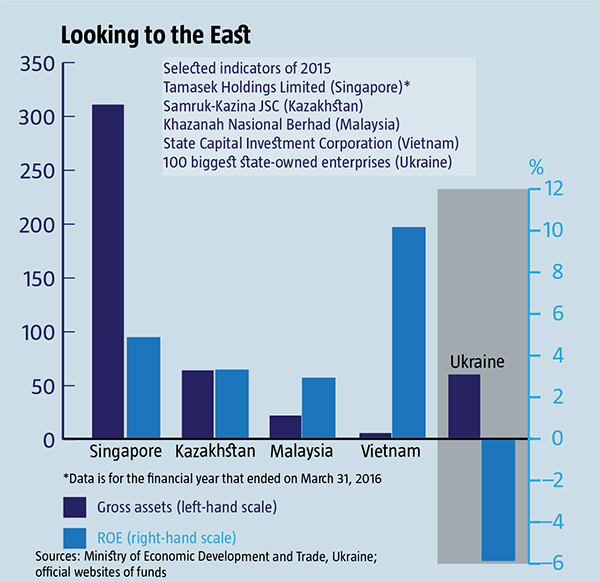

Is it just that top officials don’t understand the advantages of the centralized model? Earlier, perhaps they really didn’t understand, as ignorance and the language barrier among government officials may have made it difficult to get a handle on world practice. But in early 2015, the Ministry of Economic Development under Aivaras Abromavicius prepared a report called “The 100 biggest state enterprises in Ukraine,” that contained an in-depth analysis of the pros and cons of the existing model, presented OECD recommendations for managing state enterprises, and outlined a step-by step reform plan with a timeline. This would have transformed the public sector to match the best examples in the world.

All that had to be done was to carry it out, but the plan remained, like many others, on paper. Only this time, the excuse is not a lack of knowledge or ideas, but a lack of political will and, to a lesser extent, the competence of those officials who replaced the Abromavicius team and should have continued his work and brought those reforms to life. When the government is filled with the Kononenko types who have no interest in reforming state ownership and other top officials who aren’t capable of it, the result of all the “reformist efforts” of this kind of team is quite predictable. And that’s what happens when the services of technocrats in the Government are brushed off.

The path of sovereign wealth funds

Let’s assume that political will is somehow found and the Kononenkos as a class disappear—that’s a different story altogether and not a very realistic condition—, what next? It’s not rocket science. World practice is to base sovereign wealth funds on public corporations and to manage them, making them efficient and increasing their value. But let’s not confuse this type of sovereign fund with the oil and gas sovereign funds that are the most common in the world, and whose main purpose is not to make the companies in their portfolio more efficient but to find places to stash windfall petrodollars.

The history of sovereign wealth funds as we know them today began in 1974, with the setting up of Temasek Holdings Ltd. in Singapore. At that time, the net asset value (NAV) of the fund was S$ 354 million and consisted of state companies that were managed by the Government of Singapore. Thanks to careful, efficient management, in over 40 years the fund has changed dramatically. Today, Temasek has a NAV of S$242 billion, around US $180bn, of which only 29% is placed in Singapore itself—the fund has outgrown its country of origin—and another 40% in other countries in Asia. In the last 10 years, the fund’s net assets have doubled. Moreover, Temasek has an AAA rating from the two top rating agencies in the world and operates on a truly global scale. What’s important in this for Ukraine is that the fund operates like a normal company, paying taxes to the state and dividends to its shareholders—including the state, through the Finance Ministry. Critically, it is institutionally completely independent of the president and government.

The history of sovereign wealth funds as we know them today began in 1974, with the setting up of Temasek Holdings Ltd. in Singapore. At that time, the net asset value (NAV) of the fund was S$ 354 million and consisted of state companies that were managed by the Government of Singapore. Thanks to careful, efficient management, in over 40 years the fund has changed dramatically. Today, Temasek has a NAV of S$242 billion, around US $180bn, of which only 29% is placed in Singapore itself—the fund has outgrown its country of origin—and another 40% in other countries in Asia. In the last 10 years, the fund’s net assets have doubled. Moreover, Temasek has an AAA rating from the two top rating agencies in the world and operates on a truly global scale. What’s important in this for Ukraine is that the fund operates like a normal company, paying taxes to the state and dividends to its shareholders—including the state, through the Finance Ministry. Critically, it is institutionally completely independent of the president and government.

Kazakhstan has three sovereign funds, of which Samruk-Kazina is for strategic investment. Set up in 2008, by September 2016, its NAV had nearly doubled, growing 191%. Without any doubt, this success was underpinned by the necessary political will and farsightedness of the Kazakh government. A maximum of transparency in the operation of the fund was made possible by the inclusion of three independent members on the 8-person Supervisory Board and one out of the five managers, the use of one of the Big Four auditing firms, and the regular publication of financial reports.

RELATED ARTICLE: How privatization of the 1990s helped create oligarchs

Vietnam set up the State Capital Investment Corporation or SCIC as its sovereign fund for strategic investment in 2006. By the end of 2015, its portfolio included 197 companies. What’s interesting for Ukraine is that these enterprises are divided into four groups: A1, which cannot be privatized; A2, in which SCIC has a controlling stake and which are slated for privatization; B1, which are to be reorganized, after which the fund will decide whether to keep or sell them off; and B2, which are to be shed as quickly as possible, including through liquidation, because they are typically small and loss-making or overly risky.

No one would ever guess, but Ukraine still has 3,340 state-owned or controlled enterprises, of which only 1,829 are actually operating. Moreover, international donors have been demanding that Ukraine sort them out into groups like Vietnam has done, which took the Government nearly three years. If this requirement hadn’t been included in the IMF memorandum as a structural beacon, nobody would have lifted a finger to do anything. Right now, there’s talk that this kind of grouping—keep, privatize, shed/shut down—has already taken place but there’s no evidence of it in public sources.

The Santiago Principles

If we take a look at every sovereign fund then we can probably find something that can and should be used as an example and a workable application. But it’s not necessary to analyze them individually as their practices have been worked out and documented. In 2009, the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds (IFSWF) was established, to which most such institutions in the world now belong, representing 80% of the global wealth of these funds. The Forum has developed the Santiago Principles, formally known as the Generally Accepted Principles and Practices of Sovereign Wealth Funds (GAAP SWF), which are 24 voluntary guidelines for the practice and management of sovereign funds interested in becoming as effective as possible.

Among the basic and most significant for Ukraine are transparent action on the part of the owners, independent fund management, the appointment of management based on transparent rules that are known in advance, operational independence from the state and government agencies, clear working rules, goals and missions, independent auditors, and more. These principles are so straightforward that it does not require a rocket scientist to understand them—and consultants can always be found to assist in their implementation. All that’s needed is some political will.

In addition to the Santiago Principles, the OECD publishes guidelines for corporate governance of state enterprises and updates them regularly. These guidelines are very straightforward and easy to understand. They can easily be applied in Ukraine.

RELATED ARTICLE: The clean-up of the banking sector after the Maidan

And so, the world has enormous constructive experience in managing state-owned businesses. If the state organizes corporate management of its assets properly and then installs the right kinds of managers and lets them run things on their own, asking only that the business perform and provide it with dividends, it can easily be an effective owner. At this point, the question of privatization need not even arise as a means of reducing corruption at state enterprises. However, it’s precisely with the desire to properly organize the way state companies operate that Ukraine has problems. This is the result of a weak-spirited society and cowardly government.

If we look at sovereign wealth funds in their entirety, of course there are those who have had their share of problems, and some that have them to this day, much like those facing Ukraine. So, even if Ukraine’s leaders are not able to invent the wheel, they needn’t do so: all they have to do is simply study foreign practice and introduce it here. That would be more than enough to take the first step away from the wholesale, debilitating theft of state assets and towards a long-distance run for global leadership in managing state enterprises effectively.

Doing it right, from the start

When Abromavicius was Economy Minister, the Ministry put together a very detailed plan for reforming state-owned enterprises that was seen as both logical and correct. Some of its elements have been introduced, while others were carried out in a noticeably distorted manner. The rest have remained on paper to this day. In looking at the changes that were actually implemented and those that need to be done, a few key points stand out.

Firstly, any step towards reforming the state enterprise governance system means the loss of cash flows for certain interested parties and that means the loss of political influence for those who undertake such steps. For these reforms to succeed, the country itself needs a leadership with a different world view, which means, in effect, new, fundamentally different individuals in power or else a government that has been put up against the wall with no economic, geopolitical or military way out and is therefore open to pressure from civil society and international donors. The greater the calm and stability felt by the current leadership in Ukraine, the less inclined they will be to give up the prizes they gained in post-electoral horsetrading. This is a truly depressing state of affairs and stirs up thoughts about the need for a new revolution.

Secondly, transparency is half the success story of reforming state enterprises: according to the Economy Ministry, most state companies produce no financial statements at all, and many of those who do, don’t publish them. If these enterprises can be made to report regularly and to undergo independent audits, if the principles for how state assets are supposed to work and how the SWF should manage them are clearly set down, along with the rules for hiring managers and drawing up the full range of contracts, this would seriously reduce the room for corrupt officials to maneuver. True, Ukraine’s law enforcement system is far from ideal today. But records of corrupt officials are plenty, and they will be afraid that, sooner or later, they will be taken to court. So all government officials who place the interests of the nation at least somewhat higher than their own and have influence over certain decisions should start by fighting for transparency in the way state assets are used.

Thirdly, the right people have to be in the right positions, which is yet another condition for successful reforms. The battle for properly performing state enterprises should be seen as a strategy of aligning honest professionals in key decision-making positions. Let’s start at the bottom. The general manager of a state enterprise needs to be a recognized professional who is paid a market salary. If an individual earns a living for knowing how to manage properly, that person’s reputation is their capital and their success in managing a company increases their personal value as a specialist. On the other hand, if that person gets involved in corrupt activities, they will be expelled from the management market and lose any opportunity to manage ever larger companies and to develop professionally. This means that an increase in the salaries of managers of state companies to 10-200 basic salaries of core employees should be established by law as the first step to attracting honest professionals to be top manages of state companies.

RELATED ARTICLE: How trading with the occupied parts of the Donbas became a handy loophole that helps evade taxes

The next step should be selecting hirees competitively through a committee of independent individuals. But if we look at the selection committees in Ukraine today, they include people from the IMF and World Bank, IFC, the EBRD and other international organizations, but these individuals have no vote. Thus, either qualified candidates don’t come to the top in the competition or the competition is cancelled several times as was the case with UkrSpirt, because, as rumors had it the winner wasn’t someone loyal to the Verkhovna Rada faction that had been given the “right” to “control” the state alcohol producer after the previous election.

The third step should be establishing companies of the necessary scale, as a successful top manager will not agree to run a grain elevator out in the boonies. And this is one of the main reasons why state assets need to be reorganized and consolidated until a sovereign fund is set up.

Now, even if the director has a brilliant reputation, the temptations are huge and this person is not guaranteed not to fall. To this end, the management of state companies should not be the job of a single individual but a team of several people who function as the management. A supervisory board should oversee the activities of the management. This is common practice around the world and it has long ago proved its effectiveness. If, in addition to this, both the management team and the board include independent individuals, typically foreigners, effectiveness and resistance to corruption increase significantly.

Ultimately, it’s not a spoon of tar that spoils the bucket of honey but a spoon of honey, that is, honest professional people, even just one or two in the management and supervisory boards, who, armed with the legal requirements for transparency in the operation of state enterprises, who can reveal the bucket of tar. The system is clear and straightforward, but the lack of political will because of the general level of weak-spiritedness gets in the way of instituting it. And so the struggle between current realities and potential ones continues, and Ukrainians continue to hope that one day things will really be better.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter or The Ukrainian Week on Facebook