On December 6th, 2021, more than two months out from the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, John Bolton, former National Security Advisor under Trump, suggested that the U.S. should deploy troops in Ukraine, in his Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty interview. That was the only hint of its kind to date. The Biden administration’s strategy however, is founded upon ‘countermeasures’ to prevent further Russian aggression. We all know how well that worked.

In fact ‘countermeasures’ are an obvious sign of foreign policy weakness. US foreign policy is on the retreat in many places across the world. The fall of the Afghan government (domino effect) in August 2021 serves as a perfect example of this. US forces pulled out of the war-torn country upon leaving expensive military equipment behind. No later than on 21st of November in 2021, the first intel came in on Russia’s plans to capture Ukraine and install a pro-Russian puppet government.

That is three months and two days of a head start. Three months and two days of preparation and maximum armament and help of all kinds. The reaction to the intel? Nothing besides warnings, condemnations and small deliveries of weaponry such as anti-tank weapons as well as scheduled sanctions should any escalation occur. Embassies of the US, Canada, Germany and many western countries subsequently announced their move to Lviv. Conveniently, an open invitation for Russia to invade. Imagine a gang-infested Chicago neighbourhood with pre-emptive and complete withdrawal of police units combined with the light armament of local business owners. How do criminologists and police officers think that would unravel? Russia saw the West’s diplomatic withdrawal as a sign of weakness. Calls for citizens of western countries to ‘leave immediately’ was seen as a green light for Putin. What a perfect gift, one would think. To put it in retrospect, one can recall a visit of Polish, Czech and Slovenian PMs on the 15th of March 2022. All of a sudden, the day was free of shelling and rocket fire in Kyiv. What a coincidence!

Rewinding back to 2008, world leaders gathered and delivered speeches in Tbilisi during Russia’s invasion of Georgia, with Russian troops a mere 50km from the place of gathering. Where was this show of solidarity in Ukraine? President Volodymyr Zelensky invited US president Joe Biden to visit Kyiv as early as on the 14th of February, 2022 – 10 days before the invasion. The invitation was kindly rejected, of course. Not even a symbolic gesture of this kind was delivered, signalling even more weakness than before.

Despite the diplomatic drawbacks of November 2021 – February 2022, it is important not to undermine the value of the early intel provided, of course. This gave Ukraine a head start in preparation for the worst. Nevertheless, scepticism on the potential invasion was quite common in the West. Putin would never go for such a high-risk conflict – all he wanted was to be protected from NATO expansion eastward it was commonly claimed. A nonsensical claim, since NATO already has a superior military force – a hypothetical Ukrainian membership would not change the balance of power. Many in the West did not see Putin’s obsession with Ukraine. European elites were convinced that Ukraine was simply a frozen conflict by the likes of Georgia, Moldova and Nagorno-Karabakh aimed to stall the country’s movement westward.

During the three months between the first intel and the invasion, the West’s policy was fundamentally wrong. The minimum-risk approach can be analysed by Game Theory, a mathematical study of strategic interactions between two opposing sides, both aiming to maximise their utility. In fact, a Game Theory scenario with a single round as well as multiple rounds can perfectly outline the stand-off. For the sake of simplicity, the example will be a bilateral interaction between the West and Russia.

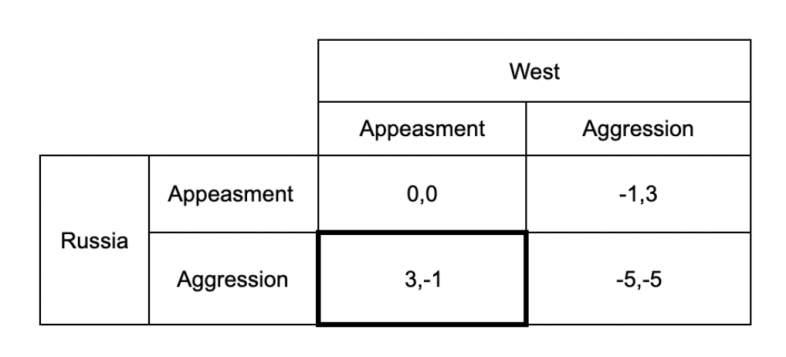

Table1. Single-round stand-off

It should also be noted that in Game Theory, all actors are rational. Russia’s rationality in this context is up for debate. The rationality of war of course can always be questioned, but in this theoretical case, Russia’s rationality is grounded upon seeing advantage and weakness of the other side when trying to gain political advantages.

The numbers in the table represent hypothetical gains of utility, in relative terms. A negative value represents a worse outcome in comparison with the status-quo (bilateral appeasement) of 0 and 0. In a one-time standoff, Russia gains from aggression if the West chooses to appease. This reflects the reality of the November-February period. The West did not hint at being directly involved in the war from the start. This ‘insider’ information made it clear for the Russians that they can take a dominant position in ‘Round 1’. They gain 3 units of utility, the West loses 1. Not so bad for the West, right? It’s only a short-term loss, in a one-off game. Putin kept raising the stakes, the West did not. Putin openly showed that he is seeking a high-risk strategy, the West – a minimum risk strategy. After all, if both went for a high-risk strategy (bilateral aggression), both could end in an equally depriving position with –5.

The West made it even easier than it could theoretically be as they made it clear they were not raising the stakes in the conflict and would stay inactive. Hence, they gave up their position and strategic aims. Russia, in this round already knew what the other side would pursue (in Game Theory this is not the case however, as all sides are theoretically unaware of the opposite side’s intentions), so aggression was guaranteed to bring a surplus of 3.

Multiple-round stand-off

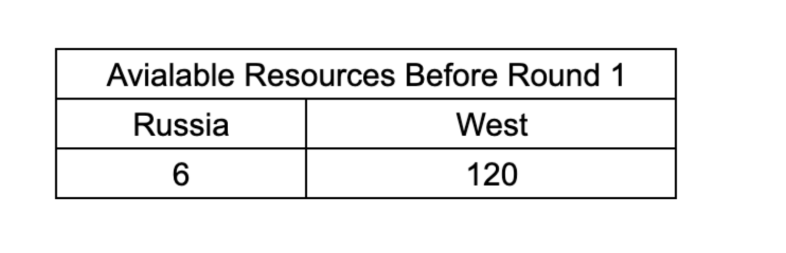

However, the prolonged war (44 days raging at the moment of the writing of this article) shows that a multiple-round game theory analogy is more applicable. If there are 10 rounds of what is shown in Table 1, and the constant position (West –1, Russia +3) remains, this amounts to a costly scenario for the West (–10). In the long-run, if the West is rational, this strategy has to be abandoned. Such unfavourable conditions should not be tolerated. A Nash Equilibrium (a stable outcome with no incentive to deviate from a strategy) that brings continuous losses to only one side should be unthinkable, especially if we consider the reality of Western resources, economy and power being far more superior.

Table 2. Multiple-round strategy

At first, it may seem that this is even more unfavourable to the West than before. –5 is a much bigger hit than –1, right? False. Let’s add another element to this strategy. As stated before, the resources of the West are far more superior to that of Russia’s. NATO’s defence spending (equated to the West in this example, for the sake of simplicity) in 2021 was estimated to be around $1.2 Trillion. By comparison, Russia’s spending in 2020 was only about $61.7 Billion. This is an outstanding advantage for the West and Russia knows this. Not to mention the superiority of the West’s economy, technological capabilities and the absence of extensive corruption among these domains. We can simplify this as a resource ratio of roughly 120 to 6. Let’s consider that for each round, the units of utility gained or lost are added or subtracted from this number. Yes, the ratio is fairly ambiguous and its incorporation with Game Theory is unorthodox (as resources as a concept are not typically combined with this). However, this allows illustrating the resource disparity in this confrontation. A potential drawback in this fused model is the apparent ‘gain’ of resources after pursuing a policy of aggression – this is of course not the case in reality, as resources tend to diminish and there are no real winners in any war. However, we could consider this as a quantitative “win” or a matter of political advantage. No one can afford infinite rounds of aggression/appeasement scenarios. Hence, it is useful to include this aspect into the model.

Bilateral Aggression in a multiple-round scenario

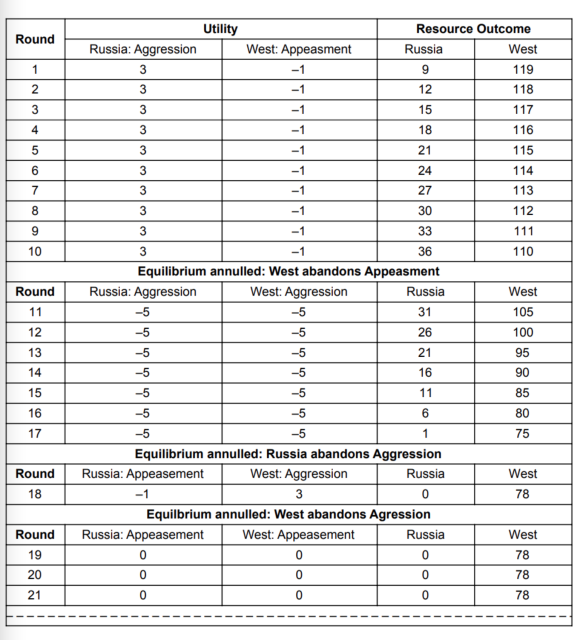

After a few rounds of Russian aggression and West’s appeasement, Russia will gain utility and its resources will not suffer. In the short and medium run, the West can afford to take small hits (–1) to its utility and resources, as it has plenty. However, if the West does choose to respond with aggression, then the double –5 scenario will deprive Russia of its resources fairly quickly. After round 10, where Russia made constant gains due to the West’s appeasement, a shift to bilateral aggression will nullify the previous Nash Equilibrium.

Table 2. A Scenario with 20+ Rounds

After 10 rounds, where Russia is in a dominant strategic position, the West chooses to pursue aggression. This plunders Russia’s resources. Soon, they lose their gains from the first 10 rounds, and are driven to 0. Russia is forced to appease to minimize their losses to –1 in round 18. This still drains their resources (at a slower pace), and they are at a point where they can no longer afford aggression at all. Seeing this equilibrium change, the West can now also shift to appeasement, seeing that Russia has backed down – after all, the West’s resources have also taken a hit (a relatively small one). This gives a path to an everlasting new Nash Equilibrium of bilateral appeasement. No one gains or loses any utility, but Russia cannot afford to go to war any longer.

Concluding Remarks

Russia has repeatedly committed war crimes in Ukraine. From a historical point of view, this is not surprising at all. Russia still embraces ideas of Stalin and other tyrannical imperialists. Putin is simply a reflection of Russia’s repressive past. There were clear warning signs of this – the two Chechen wars resulting with up to 200,000 civilian deaths, incursion of Moldova, invasion of Georgia, Syria, Crimea, Donbas and now a large-scale invasion of Ukraine. Putin always played a maximum risk game – the West’s weakness and evident retreat only encouraged him. Who would expect a tyrant not to raise the stakes if the predictable reaction would be minimal?

The optimal strategy for the West, a much larger and stronger opponent, is not to ‘deter’ Russia. Retreating is not deterring. The West must pursue a more aggressive strategy and must get involved directly as shown in the Game Theory example. Weakness is always exploited, strength – is not. The West must take action at the cost of potentially higher risks. Henceforth, NATO must get involved in Ukraine directly one way or another. This is the single best way to minimise human suffering and global economic instability. The West’s ‘aggression’ should therefore be encouraged – no more retreating and movement of embassies further west.

What would direct involvement look like? Anything ranging from direct military involvement to a tenfold increase in heavy weaponry deliveries – the former being far more effective, of course. Perhaps, we are already seeing the early stages of the West’s ‘aggression’. As of 7th of April, 2022 the US senate approved a lend-lease package to Ukraine, entailing massive military aid. Hopefully, this is a first step to many.

All in all, the weak ‘deterrence’ policy was driven by a sharp decline in the US hawkish military policy. The US chose to get involved in Iraq due to the supposed discovery of MODs, the failure of Afghanistan and an inconclusive involvement in Syria led to a sharp decline in public opinion regarding foreign military interventions. After numerous failed and arguably unnecessary or inconclusive involvements, it seems that the western citizens do not support direct involvement in Ukraine. Sensing this, western governments know that any steps in this direction will decrease the likelihood of their re-elections. This collision between the electorate and the elite uncovers the absence of a powerful intellectual stratum. To resolve this, there must be a consolidation of elites, one that the government must consult on such issues. Otherwise, governments become victims of their own populism.

Higher-risk and confrontational policy can be seen with regards to countries like Iran, but overall, democratic states do not often pursue this strategy. Authoritarian states on the other hand, seem to practice it left and right. In the name of democracy, the West has to raise the stakes and change their approach. Western governments must do the right thing regardless of their popularity, a sacrifice they have not been willing to give thus far. It would be, however, an act of true leadership.

Bogdan Tsupryk, 07.04.2022

Political Analyst