Although the question of housing never seems to be the focus of broad public debate, it also never loses its urgency. A significant share of Ukrainians today live in fairly difficult conditions, and in time this situation is likely to grow worse.

Most of Ukraine’s housing stock was built in soviet times and has since become both old and outdated. Uneven socio-economic development has added to the problem: the flow of internal migrants tends to move from the stagnating provinces to Kyiv and the oblast centers And although the sudden strengthening of the hryvnia has forced the property market to go into hibernation, the overall trend remains the same. Far from all ordinary Ukrainians can afford quality housing and this problem is not being tackled. This means that, sooner or later, Ukraine will have to come up with a directed national policy regarding housing.

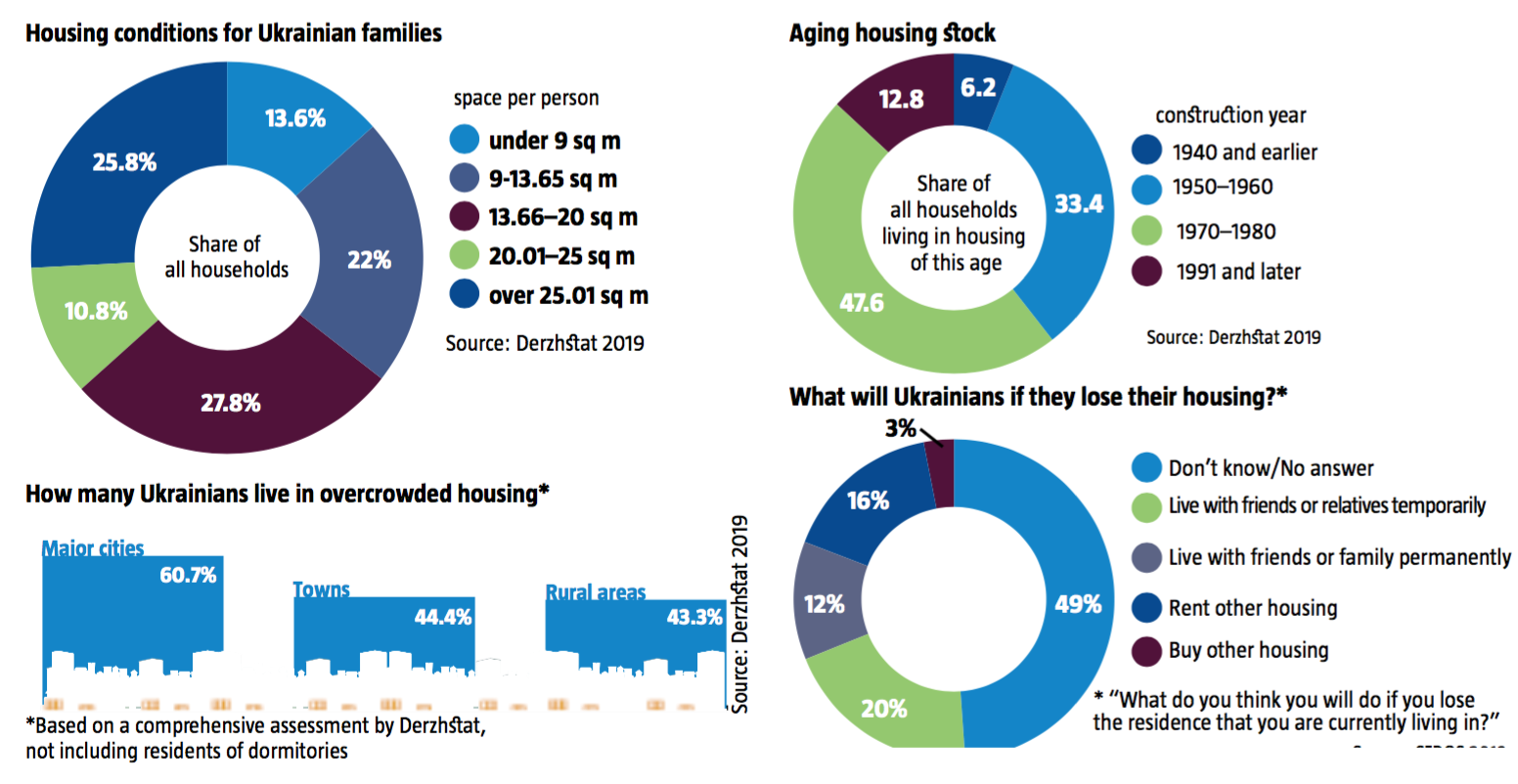

First of all, many Ukrainians simply live in housing that is tight. Officially, the rule for housing space is relatively small: 13.5 sq m or 135 sq ft per person. According to official statistics, more than a third of Ukrainians have this much or less to live in (see Housing conditions for Ukrainian families).

However, the problem is not just about size of the space, but also the suitability of housing to the socio-demographic profile of a given household. For instance, following EU-SILC methodology – EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions – a single room is sufficient for a married couple, but for two teenagers of different genders, it’s not. Moreover, European norms are that a family should have a separate room for general use. This means that even a married couple with no children should have a two-room apartment, not just a studio.

RELATED ARTICLE: Is this the end of “the era of poverty”?

This last criterion is certainly not typical of the communal traditions in Ukraine that were shaped in soviet times. And so, in assessing living conditions, Derzhstat, the state statistics service, follows what’s called EU-SILC-1, that is, one room less. Its monitoring nevertheless shows that half of Ukrainians live in overcrowded conditions, including more than 70% of children under 18. This does not even include those living in dorms (see How many Ukrainians live in overcrowded housing).

Secondly, in addition to the number of rooms and the overall living area, the level of basic infrastructure needs to be considered. For instance, whereas in major cities, indoor plumbing is enjoyed by 98.5% of families, in the countryside, less than 60% have such conveniences as running water and sewage systems at their disposal. This goes for baths and showers: where almost all urban dwellers have then, only 54% of rural Ukrainians did in 2019, according to Derzhstat.

Yet these are not the only basic conveniences housing should have. In assessing the quality of living conditions, the physical state of the buildings themselves needs to be considered, as well as their age. Only 13% of Ukrainians live in housing that was built since 1991, while nearly half live in soviet housing stock (see Aging housing stock). The Ministry of Community and Territorial Development (MinRegion) offers different numbers for the age and depreciation of housing: from 50% to 80%. Theoretically, such buildings may meet all the nominal criteria for convenience, but can hardly be called reliable or high-quality, as their lifespans have long passed. In short, a large number of Ukrainians live in crowded conditions, sometimes lacking the most basic conveniences, and a majority live in old buildings that need major repairs and even complete renovation.

Of course, in most cases, Ukrainians’ subjective feelings about living in their homes are much more positive than the objective conditions of those same homes. According to Derzhstat, 45% express some degree of dissatisfaction with their housing, while 55% say they are perfectly satisfied. Similar numbers came up in a 2019 CEDOS study carried out among residents of urban areas with a population of 100,000 or more: 53% were satisfied with their buildings, with only 25% dissatisfied; 67% were happy with the number of rooms, with 20% not happy; 67% said they were ok with the amount of space, with 20% dissatisfied. But a solid 77% stated that they felt neither the desire nor the need to change their residence

Given the real state of affairs in the housing stock, this kind of positive mood among Ukrainians can be seen partly as cultural habit or partly as simply insincere. But it could also be a consequence of the fact that most don’t have any options for changing their housing and are happy enough to adjust to what they have. The reasons for this are very simple: according to CEDOS, 89% of those who say they would like to change where they live admit that they just can’t afford to do so. Should they lose their housing for whatever reasons, more than 30% of Ukrainians expect their friends and relatives to help, while nearly half have no idea what they would do in such a situation (see What will Ukrainians if they lose their housing?).

The gap between housing needs and modest means is pushing Ukrainians to accepting poor compromises. These include buying cheaper but overly small housing or housing that is of poor quality. The latter includes not only depreciated stock that is actively being traded on the secondary market, but also “budget” new apartments that have been erected by untrustworthy developers in violation of construction regulations and so on.

And when one group of problems is resolved, others immediately emerge. This means, ultimately, that the government must start attention to the housing question. First of all, the large-scale renovation of depreciated buildings needs to be set in motion. Ukraine has had a law on the reconstruction of old housing stock since 2006, but because many of its mechanisms were never properly developed, nothing has happened in 13 years. In spring 2019, MinRegion submitted a bill to finally launch the process of renovation. After the government changed hands, this bill went on hold and only in December was it finally presented for public debate. So it’s early now to talk about any practical steps and the reality is that legislative initiatives can go into suspended animation at any stage. Should renovation actually go on track, this will only postpone a serious housing crisis for 10 or 20 years.

RELATED ARTICLE: The culture of poverty

Yet another way to ease the housing problem could be legalizing the rental market. Right now, renting is also a poor compromise as this area is almost entirely “under the table.” Experts can only really guess at the size of this market because it’s not largely invisible to both sociologists and tax collectors. Being in the shadows, the market is more dynamic, but also riskier, as both the owners of rental units and the tenants in most case are not protected by legally functioning contracts. The last time legalizing the rental housing market came up for discussion at MinRegion was in August 2019, just days before the Cabinet was replaced. Since then, neither the Honcharuk Cabinet nor government agencies have brought it up. It’s just a matter of time, because, so far, every Ukrainian administration has actually promised to bring order to this market… So far, of course, nothing has been actually done. On option would be for the government to become a market player. In 2015, a bill proposing just this was presented by the then MinRegionBud, but it too never came to much.

However, rentals are just a temporary solution. In addition to inheriting it, most Ukrainians can acquire housing to own in two ways by taking advantage of one of the state programs available or by buying it. The state programs are unusually varied, with special programs for young people, the military, police officers, railway employees, educators, the handicapped, IDPs, orphans, government officials, judges, and so on. Even so, taken together they aren’t enough to solve the housing problem on a national scale. For instance, the management of the State Housing for Youth agency was proud to announce that they had issued housing to 39,000 Ukrainian families over the last 25 years – about 0.25% of all households. Needless to say, a broader housing program would be very welcome among Ukrainians, given that 70% believe that every citizen should have the right to own their own home, provided by the state according to the 2019 CEDOS study. And there’s no point in telling people that this kind of populist dream is unreal and even dangerous.

RELATED ARTICLE: Social policy: Entrenching poverty

Ultimately, the only realistic way to resolve the problem with housing is to improve the buying power of the average Ukrainian. In practice, this includes making mortgage rates more reasonable. Today, a mortgage is just another bad compromise as annual rates are typically close to – and sometimes even higher than –20%. No surprises that people are reluctant to commit themselves to this kind of burden. Meanwhile, mortgage rates in Bulgaria average about 5%, they’re nearly 2% in Lithuania and Slovakia, and in Poland they are around 4%. According to PM Honcharuk, the Government has plans to get rates down to 12-13% by working with the NBU. Whether they will be able to reach this level, like other ambitious goals, remains to be seen. But for now, millions of Ukrainians will continue to live overcrowded in their old buildings, learning to be happy with what they have.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook