Ukrainian and Russian officials keep reciting their parts diligently in the play called “the gas war” yet mutual frustration can no longer hide behind words and gestures. The Ukrainian government did not expect Russia’s tough stance on gas price. It looks like the Party of Regions has convinced itself that standing alone by the steering wheel in Ukraine is sufficient for the Kremlin to make concessions. Russia has underestimated the motivation of Mr. Yanukovych & Co to administer the resources of the country they rule without handing over its sovereignty to bodies where the Russian Federation controls over 2/3 of all votes, such as the Customs Union.

Yet, saying that the “war” between Russia and Ukraine is inevitable while the government is fiercely protecting national interests is an over-simplification.

EXCHANGE OF GREETINGS

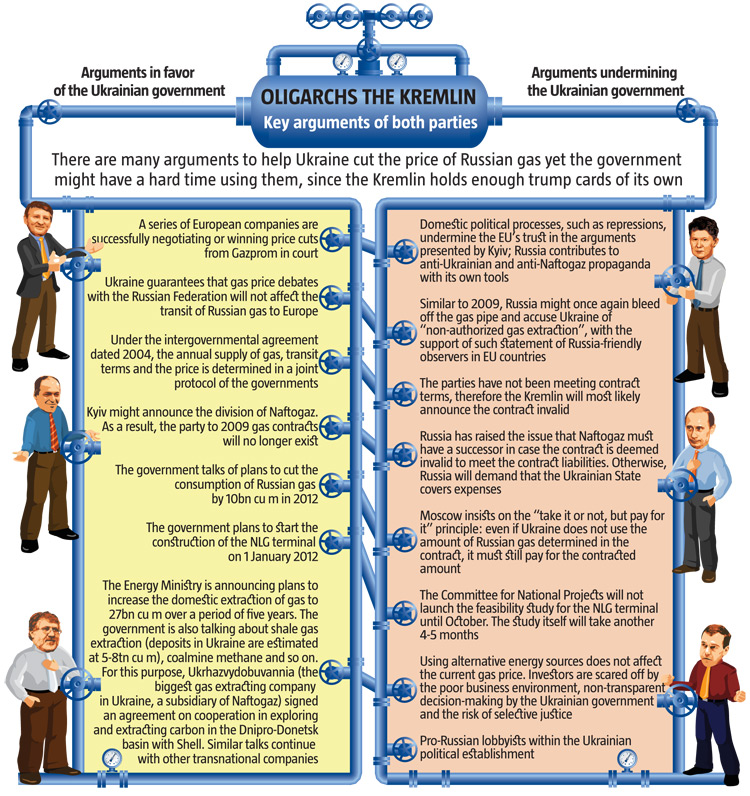

On 29 August, Mykola Azarov said he had warned Vladimir Putin that: “You are pushing us into a dead end where our only way out will be to terminate the contract.” The contract entails negotiations whenever any party claims the market situation has changed dramatically and the price no longer meets the market value of gas. Should the parties fail to come to a written agreement about price review within three months, each of them has the right to take the case to arbitration in Stockholm.

Later, news surfaced of a potential radical mechanism for the liquidation of Naftogaz and the establishment of three separate companies on its basis for transiting, selling and extracting gas, as provided for in the EU’s 3d Energy Package. On 2 September, Viktor Yanukovych instructed the government to submit draft laws on the amendment of laws for reforming Naftogaz “as a result of Ukraine’s joining the Energy Community and the need to adapt Ukrainian legislation to that of the EU” to the Verkhovna Rada for consideration. He did this two and a half years after signing the Brussels Declaration that entailed theses moves and 18 months after undertaking relevant commitments – a requirement for joining the Energy Community.

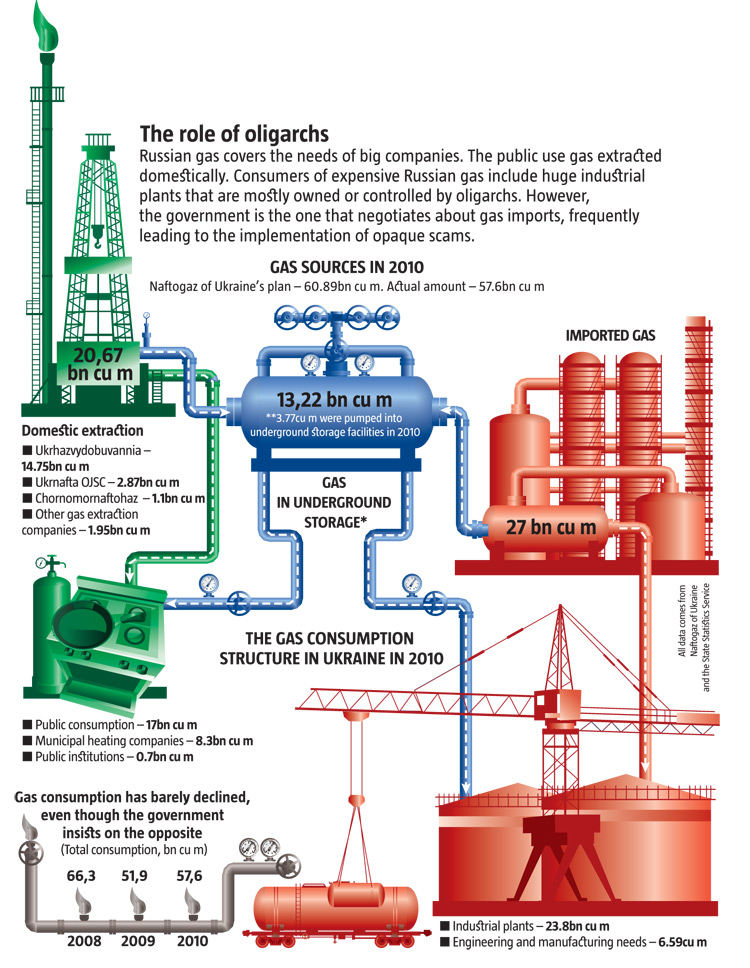

However, the problem of Ukraine in its gas conflict with Moscow is the latter’s utter conviction that Mr. Yanukovych’s regime is bluffing and is incapable of being independent of Russia’s energy hold. Konstantin Simonov, President of the Russian National Energy Security Fund (NESF), has admitted that Gazprom will run into big troubles should dramatically Kyiv cut its imports of Russian gas. “These statements are a typical trick of Ukrainian government,” Mr. Simonov claims. “When our talks about gas price end in a stalemate, Ukraine always says “we don’t need your gas”. The Ukrainian government probably thinks that this is an effective way to exert pressure on the Russian Federation, but in reality, it has no choice other than to continue such imports”.

This is why Russia is determined to break Ukraine’s resistance, saying that Kyiv must meet the commitments undertaken earlier; that it is “bluffing”; and that Ukraine should join the Customs Union “completely” and the unacceptability of any other form of cooperation. On August 31, Dmitri Medvedev went as far as to say that Russia was “subsidizing” Ukraine while Premier Putin once more repeated his usual mantra on liberation from the “dictatorship of transit countries”, as he opened the “North Stream”.

Lower-level Russian officials expressed themselves more harshly. Gazprom CEO, Alexey Miller, stated that there was only one way in which Naftogaz could be re-organized – by means of a merger with Gazprom. Otherwise, Russia would follow a single-minded policy of forcing the company to go bankrupt. “In any case, Naftogaz will pay for at least 33bn cu m of gas,” Mr. Miller said. “These are the terms of the effective contract: take it or not, you have to pay for it.” Konstantin Simonov warned that Ukraine would “have to pay for the gas it did not receive as well as penalties… in the amount of up to 300% of its value. Such is the gas business”.

In addition to firing arguments at each other, Russians have turned on their TV. Local TV channels, including the state-controlled Channel One, pour criticism on Viktor Yanukovych. They mention every tiny detail, from broken promises to Russify Ukraine, to the rejection of the Customs Union and integration of gas transport systems.

EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE

Ukrainian politicians say that they are still hoping that negotiations will continue. Regardless of the ever more heated statements made by both parties, on 6 September, Naftogaz announced that it had paid USD 487mn for Russian gas supplied in August. Although the price will grow to USD 354 and USD 388 per 1,000 cu m in Q’3 and Q’4 this year respectively, Naftogaz says nothing of its intentions to stop meeting its contract liabilities.

Both Kyiv and Moscow are doing their best to present themselves as perfectly compliant with international law in front of the EU, the third party in the gas triangle and the major consumer of Russian gas. If the situation goes so far that Ukraine decides to stop fulfilling the contract, it will be the EU’s position that will determine the winner. In the earlier conflicts of 2006 and 2009, the governments of Ukraine and Russia managed to come to terms without involving the EU, even though the quality of the final compromise raised questions. However the experience of 2009 showed how skillfully Russia manipulates its leverage to affect public opinion and politicians in EU countries, starting with the circulation of information that it is namely because of Ukraine that Europe faces the threat of “cold pipes” that are empty of Russian gas and ending with pro-Russian advocates calling on the EU to impose sanctions against Ukraine.

In 2011, Ukrainian government has done everything possible in domestic politics to turn European countries against it. Virtually everyone has already claimed that proceedings against opposition members were politically motivated and that Yulia Tymoshenko’s arrest was the final straw, as Europeans mostly dropped diplomacy when speaking to the Ukrainian government. The French Ministry of Foreign Affairs has even brought into question the signing the Association Agreement should political persecutions not be brought to an end. While we share the frustration of the Europeans, at the same time, it is impossible to forget something else: taking away the prospect of Ukraine joining the EU will have a totally opposite effect to the original goal. If this happens Kyiv will lose any reason, even if purely formal, to comply with European norms. The oligarchs, in ttheir turn, might be tempted to “sell everything and flee this hopeless country” rather than keep playing against their Russian rivals hoping to be accepted by the club of rich Europeans at some point in return.

The litmus paper regarding the position of European politicians will be discussions on the prospects for Ukraine’s signing of the Association Agreement and Free Trade Zone Agreement, which is scheduled for 12 September at the European Parliament. The draft resolution that has been leaked to the Ukrainian media calls on the EU to speed up the signing and ratification of these documents. But the resolution was drafted in July, before the arrest of Ms. Tymoshenko, thus the debate could turn out to be quite passionate.

…UNTIL TROUBLE TROUBLES YOU

Ukraine’s problem is that it has approached yet another “war” unprepared. It is well known that victory in wars comes from a systemic response rather than courage. Ukraine lacks the former, since the structure for making decisions in Ukraine relies too heavily on the short-term interests of oligarchs.

This sometimes results in paradoxes. For instance, Mr. Azarov says that the construction of the NLG terminal will start early next year, while the Committee for National Projects chaired by Vladyslav Kaskiv reports on an upcoming 4 to 5 month-long feasibility study. The latter looks more likely, since various interest groups are still competing for control of “the new gas gate”, the two key rivals being PR’s Andriy Kliuyev and tycoon Dmytro Firtash, or, more specifically, the entities linked to them. Similar issues arise when it comes to drawing investment into the extraction of gas and its substitutes in Ukraine, i.e. non-conventional carbon such as shale gas and coalmine methane. In the end, all the backstage hustling scares off investors and drags out the exploration and extraction of minerals that even without this will take more than one year.

The effectiveness of decision making is another headache. Clearly, choosing advisors is up to the government, but talk of the “prospect of a gas war” sounds weird, particularly given the fact that the Presidential Administration employs citizens of the Russian Federation or people who are proud of working for the sake of “bringing Ukraine and Russia closer together”. For example, in one of his interviews, Ihor Shuvalov, First Deputy Premier of the Russian Federation, accented his role in telling the Ukrainian government how Russia would respond to its decisions. Strangely though, the gas turmoil has bypassed Andriy Portnov, an Advisor to the President, who had drafted gas contracts together with Ms. Tymoshenko back in 2009, while now observers claim he that was involved in the decision to arrest the ex-Premier that came like thunder out of the blue.

On the whole, the maneuver space for the Ukrainian government will now be limited by a slew of factors including the chance to make Ukraine’s gas market more European under the Brussels Declaration – something that would, at the same time, significantly undermine Gazprom’s position – wasted for almost 18 months now; concessions in the form of state sovereignty and strategic objects; the loss of potential allies in the Ukrainian political environment and electoral support, something Moscow sees very clearly, causing the Kremlin to doubt the ability of the current regime to withstand a possible gas war; and the cooling of relations with the West.

As a result, Mr. Yanukovych might face the fate of Mr. Lukashenko who found himself between the devil and the deep blue sea at a critical point in time, rather than continuing to walk a fine multi-vector line between Russia and the West. On the one hand, the Belarusian scenario means turning to the Customs Union and handing over Ukrainian gas transit system that will lead to the loss of sovereignty and eventually power. On the other hand, the current government’s preparation for a “war” with Russia looks more like a myth that the government is using to win back at least some of the electorate. Meanwhile, internal conflicts within the party in power and the overall situation with the decision-making process make it super-difficult to effectively combine the diplomatic, informational, organizational and economic moves necessary for a successful campaign to change the effective gas deals. Especially, given the crowd of Russia’s supporters among those in power. Under such conditions, there is only a “slow”, yet only right way out. Having survived the shock of growing prices for fuels, as Western Europe did in the 1970s and Eastern Europe did in the 1990s, Ukraine should start cutting energy consumption in the economy, develop the domestic extraction of fuel and introduce alternative energy sources. Movement in this direction should already have been started yesterday. The critical growth of the gas price will, at the very least, possibly push the Ukrainian government and oligarchs in this direction tomorrow.

ANOTHER BATTLEFIELD

Some European consumers of Russian gas have similar demands to those of Ukraine, and sometimes these are eventually satisfied. At the end of August, Leonidas Dragatakis , the President of DEPA, a Greek gas buyer, said that negotiations to cut the gas amount to an “acceptable” level of 70% of the contracted 3bn cu m and the price of Russian gas under Greece’s long-term contract with Gazprom were completed successfully in July 2011. Italy’s Edison also negotiated price cuts with Gazprom at the end of July.

Gazprom is in the middle of a big-time gas war with E.On Ruhrgas, one of its major European gas partners, that has already taken the case to the arbitration court. E.On Ruhrgas is seeking to adjust contract prices to rates that meet spot prices for gas in Europe.

On 31 August, Radoslaw Dudzinski, Vice-President of the Polish PGNiG, claimed his company would continue to demand that Gazprom cuts gas price for nearly 9bn cu m of gas that the company is buying from it. Talks have been on-going since February 2011. If necessary, PGNiG will also to apply the arbitration court.

In 2010 and early 2011, Russia’s gas monopolist negotiated a review of contracts with E.On Ruhrgas, WIEH, WINGAS, RWE (Germany), GDF – Suez (France), ENI, ERG, Sinergio Italiano, PremiumGas (Italy), GWH Gashandel GmbH, EconGas (Austria), GasТеrra (Netherlands), EGL (a transnational gas sale company operating in Europe), and SPP (Slovakia). All of the above examples involve companies in the process of economic debates. With Ukraine and Russia, though, this is more about politics than anything else.