… My cell phone automatically switches to a Belarus operator two kilometers before the Belarussian border. My calls home to tell parents that I got stuck here become a challenge. Not getting stuck here is even more of a challenge: the bus to Ovruch, the nearest town, comes rarely. Until recently, kids from a Belarussian village just across the border went to the Ukrainian school in Voznychi, a village on the Ukrainian side. Then border control tightened and the school was closed down. Thickets have gradually taken over the village ever since. Around it lie the pristine forests of Polissia[1].

Wild and noble

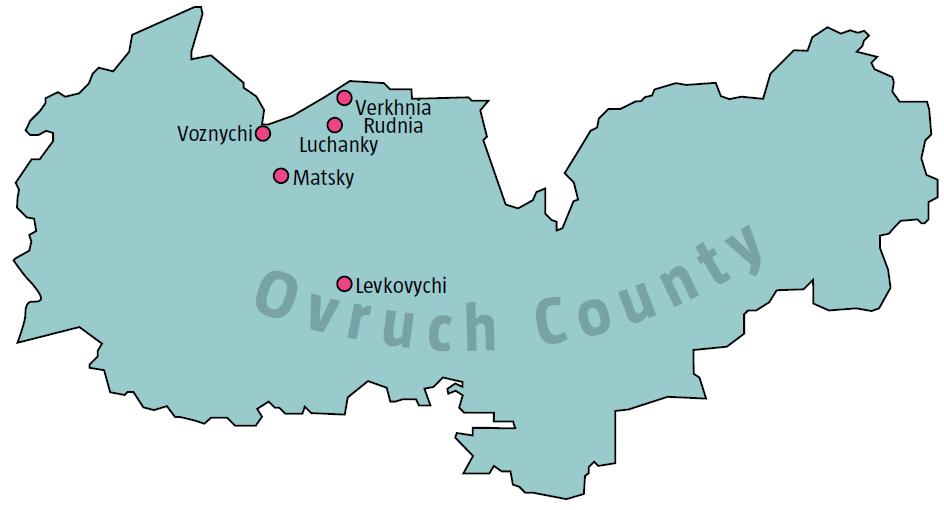

The Nevmrzhetskis and the Levkivskis are two families descended from the nobility of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania[2]. Many more have lived in the local villages Voznychi, Luchanky, Levkovychi, Matsky and others since the 15th century. “They probably settled here even earlier,” says Serhiy Kovalchuk, head of the village council, “but nobody has dug deeper into their family tree.”

Mr. Kovalchuk is a man of the world. With two university degrees and many trips around Europe, he finally settled in the small village. The speed of urban life is not for him, he says. He edits historical and ethnographic research papers and is working on one of his own right now, collects bits and pieces of local history, starting with the Stone Age, and is looking for information about people who disappeared during the Second World War or Stalin’s repressions to pass it on to their descendants. Each search is a real detective story. Mr. Kovalchuk makes sure that the heroes are duly honoured – be they Ukrainians or Germans who didn’t allow soldiers to strike a match and set a church full of people locked inside on fire. Or, at the very least, known.

Like all the locals, he is very distrustful. He takes his time scrutinizing my journalist ID but even after agreeing to talk to me, insists that the recorder is not switched on. In the end, I write down the entire conversation by hand.

Fear of recorders and cameras is omnipresent here, although the locals are curious, sincere, funny and friendly. They will eagerly leave whatever they are doing to talk to strangers walking down the street, tell their family history or that of the village, invite them to dinner or to stay the night, show them around the house and the backyard. But one rash move towards the camera and the contact is lost. “I’m not pretty, I’m not dressed well, take photos of someone prettier,” a nice-looking young woman says.

“They still remember Stalin,” a man in the village of Verkhnia Rudnia explains why the village head prefers to speak off-record. Here, memory is transferred on a genetic level. So are the memories of the villagers’ medieval origin.

“Don’t confuse them with the Polish nobility!” Mr. Kovalchuk says. “They are the Ukrainian okolychna shliakhta (suburban nobility – a class of impoverished noblemen, most of them with no land that emerged after the division of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth – Ed.).” One such nobleman was Yuriy Nemyrych, a colonel in Bohdan Khmelnytskyi’s army who initially fought against Khmelnytskyi, but decided to make a deal with him once he realized that he would not defeat the hetman. Mr. Kovalchuk denies that these families have Polish roots but historical turns intertwined the Ukrainian and Polish nobility so often that very few historians would be able to decipher the twists and turns of their genealogy.

With the Levkivski family, things are much clearer: Larion Valevskyi is considered to be the founder of the family. Prince Olelko Volodymyrovych, the grandson of the Lithuanian Great Prince Olgerd, granted him this land in 1450 for services rendered, although what these services were is unknown. The deed awarding the land said: “Neither he nor his servants are obliged to serve us, nor should he pay any taxes; he is also not obligated to guard Chornobyl, but shall do service with the boyars[3].” Successive princes reaffirmed these privileges for “the biggest suburban noble family”.

In other words, serfdom never existed in these villages. The locals did not pay taxes. Their only duty was for each family to send one man from each household once every two years to patrol the border on a horse for a period of six months. Nearby villages where muzhyks – peasant serfs – lived, experienced serfdom. A nobleman could not marry a common woman. This tough divide has survived to this day. The two families try to marry among themselves, their members being fully aware of their aristocratic roots.

“When there was no heaven or earth…”

At one time, the village of Luchanky had an impressive collection of stone tools that had been found there. This was later taken to Zhytomyr.

Before (and after) Princess Olga burned down Korosten, these lands were inhabited by the Drevlians (a tribe of Early East Slavs in the 10th-16th centuries. Their name derives from the Slavic word derevo – tree. They fervently opposed attempts to annex them to Kievan Rus but were eventually conquered. Prince Oleg made them pay tribute to Kievan Rus in 883 but they stopped after his death. After Prince Igor tried to reinstate the tribute, they killed him. His wife, Princess Olga avenged his death by destroying their capital, Iskorosten (now Korosten) and other towns – Ed.) They did not accept Christianity until 120 years after Christianity was accepted in Kievan Rus in 988. Slavic pagan names and legends come to life here. Yivzhyn wells (Princess Olga’s wells) were dug by her troops during the advance on the Drevlians to avoid drinking water from existing wells, which the Drevlians may have poisoned. These wells were guarded 24/7. Mr. Kovalchuk learned these and many other legends from his grandmother who could not read or write. The name of Lelchynskyi Raion (Region) in Belarus comes from goddess Lel; Babyna Hora – Grandmother’s Mount – is from Baba, the goddess of the forests and fields; Divoshyn and Divyna Hushcha (Maiden Thicket) are named after Diva, a younger version of Baba. Kapyshcha for them, i.e. the part of pagan shrines behind the altar where the statues and images of gods were located, were always close by.

Every Easter, local youths jump over bonfires, tell fortunes and roll fire wheels – these are all pagan rituals. They always go to church before or after these rituals. This place is a natural fusion of old and new traditions.

Since almost all of the people in the village have Nevmrzhetski as their surname, the locals use a three-level system of names: 90% of the locals have the same surname; the family name – Kysli (Sour), Leiba (for friendship with a Jewish family), Zubati (Toothy), Dolya (Fate), Kruts (Nail); and nicknames. While the family name is used officially for postmen, nicknames are seen as more insulting, a kind of mockery.

READ ALSO: Mission: Discover Polissia

Beekeeping is one of the main industries here. The technology used has barely changed since the times of Kievan Rus. Hollowed-out tree trunks are placed as high as possible on other trees. That’s where the bees live. These apiaries are heated in winter. Much of the honey is sold.

The locals still plough their land, part of which is under rye. They also make their own bread.

Quite a few Luchanky-born secondary school graduates manage to enter top Kyiv universities. Could this be one of the positive manifestations of their blue blood?

The neighbouring village of Verkhnia Rudnia barely differs from the “noble” Voznychi and Luchanky. However, the gap between them is much deeper than the five kilometers of forest road. People there are equally friendly, inviting us to their homes and asking us why we’re there. “Oh, so you’ve visited those lords?” the host wonders mockingly. “When their guy marries our girl, his whole village baits him for taking a common woman.”

“Blue blood, blue blood,” the host continues. Suddenly, a smile lights up his face. “Not that blue anymore… The Germans have mixed in some of theirs. Did you see how many people there are blond? There you go!”

While Crimea and the Carpathians are comfortable exotic destinations with well-mapped tourist routes and all the necessary facilities, Polissia is wild, unpolished and authentic. You will not find a comfy hostel, cafe or a souvenir shop anywhere here. Instead, you will experience the life people lived many centuries ago. Every spot and stone here has a story not yet told in history books and the people who know and retell all these stories are still alive. It is unknown whether these villages will die out like many others did, whether their noble villagers will assimilate or savvy young generations will turn them into standard popular traditional tourist destinations. For now, you can be here, listen and watch here, and absorb the rich and full memory with the air.

[1] Polissia or Polesie – “covered in forest” in Ukrainian – is a natural and historic region, part of the old Slavic proto-homeland. It mostly covers Northern Ukraine and Southern Belarus, as well as small parts of Russian and Polish border territories. Just like the Carpathians, it preserves the oldest relics of proto-Ukrainian and proto-Slavic cultures. Chornobyl is located there.

[2] The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state from the 12th century until 1795. It expanded to include large portions of former Kievan Rus and other Slavic lands, covering the territory of present-day Belarus, Latvia, Lithuania and parts of Moldova, Poland, Russia and Ukraine. At its peak in the 15th century, it was the largest state in Europe.

[3] Boyars were members of the highest rank of the feudal Moscovian and Kievan Rus aristocracies in the 10th-17th centuries. Only the ruling princes were superior.