When redrawing administrative borders, the leadership of the Russian Empire always turned a blind eye to the ethnic borders of the people inhabiting them. The goal of creating ethnically mixed provinces was to hamper national consolidation within the “great and undivisible” Russia and facilitate assimilation with the titular Russian nation. Restored after the collapse of the Romanov’s empire in 1917-1920, Ukraine immediately faced the dilemma of the annexation of Eastern Ukrainian territories, which at that time, were part of Voronezh and Kursk Provinces, the Don Army Oblast, Kuban and the Stavropol Province.

THE FAILED ANNEXATION

When shaping the territory of the UNR (Ukrayinska Narodna Respublika) or Ukrainian People’s Republic in November 1917, Central Council officials viewed Eastern Slobozhanshchyna as part of Ukrainian autonomy. Under the UNR law dated November 29, 1917, the Central Council announced the election to the Ukrainian Constituent Assembly in Putivl, Grayvoron and Novyi Oskol Counties of the Kursk Province, and Ostrogozhsk, Biriutski, Valuyski and Boguchar Counties in the Voronezh Province. However, this region remained beyond the Ukrainian government’s control as the war with the Russian Bolsheviks unfolded.

After the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed with the Central Powers, the Central Council issued a law on the administrative division of Ukraine, dated March 2-4, 1918 whereby the Podonnia territory covering ethnic Ukrainian counties in the Voronezh and Kursk Provinces with Ostrogozhsk as its center, was integrated into the UNR. Belgorod County was divided between the Kharkiv and Donetsk Oblasts of the UNR. However, the declaration failed to transform into the actual integration of these territories into Ukraine, which only became possible under the Hetmanate of Pavlo Skoropadsky.

AN ETHNIC DEVIL`S TRIANGLE

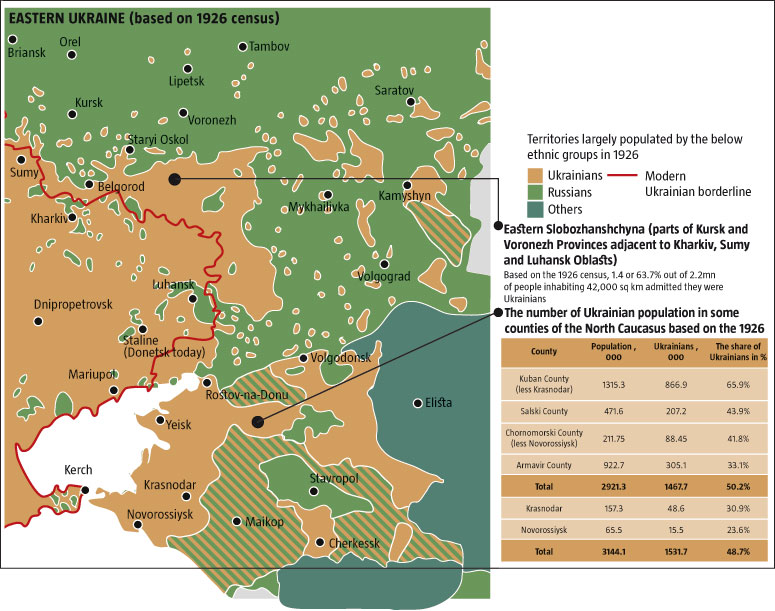

After the Bolsheviks overthrew the Hetmanate and occupied the Dnipro territories of Ukraine[1], Eastern Slobozhanshchyna and Podonnia were once again annexed to Russia. Administratively, the then Eastern Ukraine became part of the Kursk and Voronezh Provinces, as well as the North Caucasus territory of the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic (RSFSR). The 42,000 km2 covered by the two provinces was home to 1.4mn people or 63.7% of the total 2.2mn population, who still considered themselves to be Ukrainians, in spite of decades of systematic russification. Yet, this huge territory along the Ukrainian border, larger than the Kursk Oblast itself, failed to become a separate administrative unit.

In the 1920s, even the administration of the Ukrainian SSR, with its extremely limited powers, insisted on reviewing the border between the two republics of the single Union. Their arguments were based on the all-Union census held in December 1926. More than 4.5mn Ukrainians lived on Russian territories bordering Ukraine. Nearly as many Ukrainians lived in Western Ukrainian villages that belonged to Poland. However, the eastern parts, even if ethnically Ukrainian, were never annexed to the neighboring Kharkiv Oblast of the Ukrainian SSR. As a result, Kharkiv, the then capital of Ukraine, was actually a border city, while the border cut through inherently ethnic Ukrainian territories.

BELGIUMIN A STEPPE

Covering an area of 293,600 km2, which was larger than the UK today and comparable to modern Italy or Poland, with a population of 8.2 million, the North Caucasus was bigger than any other USSR republic, other than Russia and Ukraine. Without the autonomous mountain republics, its territory covered the current Krasnodar Krai, Stavropol Krai and Rostov Oblast. The ethnic and language structure of the territory was somewhat similar to the modern Belgium or Switzerland, since the territories of the Free Don and Kuban that were an ethnic mix of Ukrainians and Russians became the foundation of the North Caucasus province after the Bolshevik occupation in 1924.

The rural population, which accounted for over 80% of the total population, remained half-Ukrainian and half-Russian, 2.7mn each, in 1920s. The traditionally russified cities were dominated by “Russians”, with 0.99mn compared to 0.34mn Ukrainians. Still, the share of urban population in the overall structure of the territory inhabitants of the territory was still quite low at that point. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian rural population made up the majority in five provinces bordering the Ukrainian SSR, including the Taganrog, Don, Donetsk, Kuban and Chornomor Provinces. It accounted for 900,000 of the 1.4mn-strong total population of the Kuban Province, 206,000 of 376,000 in the Donetsk Province, and 191,000 of 265,000 in the Taganrog Province. Provinces located farther from the border had 30% to 50% of Ukrainians. The latter were only few in the industrial Shakhty-Donetsk County.

SOVIET CYNICISM

While stigmatizing the Polish occupational regime for persecuting and assimilating Ukrainians in Halychyna, Volyn, Kholmshchyna (Chelm Land) and Pidlyashya (Podlachia), official soviet propaganda cynically ignored the reasonable requests of the latter to annex Eastern Ukraine to the Ukrainian SSR within the “brotherly Union.” In the meantime, the Bolshevik regime, despite its declared intent to resolve the national issue fairly, continued to implement its policy of forced russification, which was traditional for all versions of the Russian empire, while Ukraine’s proposals to divide administrative units along ethnic borders were consistently ignored.

In the mid to late 1920s, these territories underwent partial “ukrainianization”, limited to opening schools and cultural-education institutions as well as the publication of a limited number of books in Ukrainian. It soon emerged, though, that the position of Eastern Ukraine within the Russian Federal SSR proved to be much worse than that of Western Ukraine under “feudal” Poland’s rule, despite the constant ethnic, cultural and religious discrimination of Polish Ukrainians.

ANNIHILATION OF EVERYTHING UKRAINIAN

Despite the defeat of the Kuban People’s Republic, Kuban Cossacks continued to resist the Bolsheviks. Compared to the guerillas of the Greater Ukraine described in “The Black Raven”, a novel by Vasyl Shkliar, who were active until the late 1920s, Kuban guerillas continued their war against the Soviet regime until the late 1930s and a small unit led by Milko Kalenyk remained until the Germans arrived in 1942. Under yet another surge of Stalin’s repression on the verge of 1920-1930s, the rural Kuban population felt ever more nostalgia for the Kuban People’s Republic, while new insurgent units often used “Long live free Kuban!” as their slogan.

The regime responded to this with terror, the key elements of which were the 1932-33 genocide of Ukrainians and the mass deportation of “kurkuls”- wealthier farmers, from Eastern Ukraine. Collectivization hit Ukrainians living in Eastern Slobozhanshchyna and North Caucasus much harder than those living in the Ukrainian SSR. An instruction “On Grain Collection in Ukraine, North Caucasus and the Western Oblasts” by the Communist Party Orgburo and the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR, signed by Joseph Stalin and Viacheslav Molotov, dated December 14, 1932 had a clear underlying ethnic motive. Ironically, the directive also condemned ukrainianization, suggested that it should be stopped and those “guilty” of starting it should be sentenced to 5-10 years in a GULAG. The regime required that all record-keeping in “ukrainianized” provinces of the North Caucasus, as well as all newspapers and magazines published in Ukrainian, be switched to Russian. By autumn, school children were taught in Russian, too.

This resulted in not only the physical killing of Ukrainians, but also their ethnocide on ethnic Eastern Ukrainian territories. When passports became mandatory in December 1932, they massively wrote “Russian” in the “nationality” column. This stuck tight in their minds as well. The census, held 10 years after the previous one (early January 1937), showed the unusual and catastrophic disappearance of Ukrainians from the abovementioned territories.

Their number dropped three fold in the Kursk and Voronezh Oblasts, which had once been Ukrainian, from 1.4mn to 0.55mn. In North Caucasus (less autonomous republics) it shrank ten fold from 3.1mn to only 310,000.

After the deportation of part of the local population, a directive issued by the USSR Military Inspection Council signed by Mikhail Tukhachevski allowed demobilized Red Army soldiers to settle on these territories, however, people born in Ukraine or the North Caucasus were categorically prohibited from doing so.

TESTING RUSSIFICATION MECHANISMS

Today, the official share of Ukrainians in regions where they had been a relative or absolute majority just 80 years ago, is no more than 1-4%, while the existence of the true Eastern Ukraine is history. Its only heritage is the sad experience of losing a mass of ethnic Ukrainians in the East. Based on sociological surveys, the local descendants of one-time Ukrainians are among the fiercest opponents in the RF of Ukraine’s independence and its development, which is separate and distinct from that of Russia.

Russification mechanisms, well-tested and perfected on these territories, focused on fostering hostility in Ukrainians to the concept of national sovereignty, were later extended westward to the Ukrainian SSR. Although the process was suspended, or at least cut back in the early 1990s, its effect can still be seen in many eastern and southern regions of Ukraine today.

*Ethnic Ukrainian territory that are currently in Kursk, Belgorod and Voronezh Oblasts in the Russian Federation and part of the Sumy, Kharkiv and Luhansk Oblasts in Ukraine.

[1]The equivalent of the current Ukrainian territory, with the exception of Crimea and Halychyna.