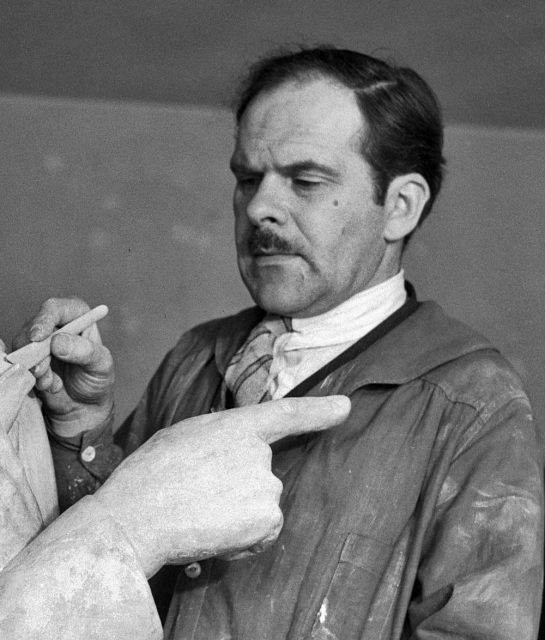

Alexander Archipenko is one of the most influential sculptors of the early 20th century. Sadly, most Ukrainian museums, whether private or state-owned, have only managed to preserve a small number of works once created by this great Ukrainian artist. When it comes to organising an exhibition dedicated to his art there are hardly any plans to hold one in the foreseeable future. Ukrainians have thoroughly researched Archipenko’s work and numerous studies were published either in Ukrainian or translated from other languages. As it happens, only individual monographs and exhibition catalogs that took place in the United States are easily accessible to public and a general reader. From the 1920s and throughout the 20th century there some essays, articles and series* were published in Ukrainian.

Alexander Archipenko never visited Kyiv again after leaving for his studies in 1906. Nevertheless, he would regularly send his artworks for the exhibitions held in Soviet Ukraine. In the mid-1930s he exchanged letters with Ilarion Sventsitsky regarding the display of his works at the National Museum of Andriy Sheptytsky**. Throughout the 1930s to the 1950s, the artist created portraits of Taras Shevchenko, Ivan Franko, and the Ukrainian Knyaz [Prince] Volodymyr Svyatoslavych.

Archipenko considered himself a Ukrainian artist. He was an honorary member of the Ukrainian American Artists Association. In 1933, he designed a Ukrainian pavilion at the Century of Progress exhibition in Chicago. In a number of interviews conducted after the Second World War he emphasised that he has always remained a Ukrainian sculptor, pointing out his ties to Ukrainian culture.

He always spoke of monumentality, which could be observed even in his smallest sculptures. “Perhaps that’s what I’ve inherited from the endless Ukrainian steppes”, he would say, possibly alluding to how the so-called Kurgan stelae, Scythian and later Cuman women, were perceived in the steppe: the endless horizon, the mound of earth and stones raised over the graves, the vertical human figure carved from the stone.

He always spoke of monumentality, which could be observed even in his smallest sculptures. “Perhaps that’s what I’ve inherited from the endless Ukrainian steppes”, he would say, possibly alluding to how the so-called Kurgan stelae, Scythian and later Cuman women, were perceived in the steppe: the endless horizon, the mound of earth and stones raised over the graves, the vertical human figure carved from the stone.

During the European period of his career (before he moved across the ocean), Archipenko applied aesthetics of the archaic sculpture, gradually altering their silhouettes, texture, density, dynamism of proportions, and its material. This transformation is particularly noticeable in his numerous nudes, which have gradually become more and more daring in their interpretation of volume and proportions, with a distinct emphasis on contour. There are famous sketches depicting exhibition-goers, especially women, back in the days, ardently reacting to Archipenko’s works. When Archipenko discovered the possibility to construct sculptural masses around emptiness, a caesura, or a void, which he proposed in his 1915 composition ‘Woman Combing Her Hair’, it became a true revolutionary breakthrough.

The sculptor may have borrowed this innovative technique, which signalled a decisive shift from the ancient tradition, from the traditional Ukrainian folk art, where there is a prevalence of a specific container known as a ‘kumanets’ – a vessel with a circular opening in the centre. The sculpture called ‘Woman-Vase’ is a prominent example when such a vessel was used as a model to transfer its design features onto the image of a female figure. In 1918, Archipenko emphasised that the absence of one body part in this sculpture could enhance its expressive power. As the composition’s name suggests, there is transfer of classical torso impressions to a vessel, even though the piece was created using bronze, the classical material. Later on, when creating replicas of this artwork, Archipenko experimented with coloured plastic and acrylic glass to enhance this impression.

Archipenko was likely the first avant-garde artist to draw upon the tradition of Ukrainian polychromy in wooden sculpture. In 1913, he created a plaster sculpture under the title ‘Carousel of Pierrot’, a Cubist composition with facets painted in bright colors. Although the round sculpture was inspired by his visit to a Parisian circus, it was also influenced by the tradition of a rural wooden polychrome sculpture that had been preserved in churches across Ukraine since the late 17th century. His experiments with various reliefs in the so-called ‘sculpture-painting’ are noticeable in the ‘Medrano’ series (named after the circus) and involved a combination of various materials such as metal, wood, glass, and papier-mâché. Archipenko glued and painted these materials in 1913 and 1914, just like the nameless artists who created figurines for the Ukrainian folk nativity scenes. During the period of cubist dominance the coloured avant-garde reliefs were also created by Volodymyr Tatlin (who called them ‘counter-reliefs’, adding wire strings) and Vasyl Yermilov, who lived Kharkiv in the 1920s. They continued the tradition of a collage-based polychromy in the aesthetics of what later became known as constructivism.

Archipenko was likely the first avant-garde artist to draw upon the tradition of Ukrainian polychromy in wooden sculpture. In 1913, he created a plaster sculpture under the title ‘Carousel of Pierrot’, a Cubist composition with facets painted in bright colors. Although the round sculpture was inspired by his visit to a Parisian circus, it was also influenced by the tradition of a rural wooden polychrome sculpture that had been preserved in churches across Ukraine since the late 17th century. His experiments with various reliefs in the so-called ‘sculpture-painting’ are noticeable in the ‘Medrano’ series (named after the circus) and involved a combination of various materials such as metal, wood, glass, and papier-mâché. Archipenko glued and painted these materials in 1913 and 1914, just like the nameless artists who created figurines for the Ukrainian folk nativity scenes. During the period of cubist dominance the coloured avant-garde reliefs were also created by Volodymyr Tatlin (who called them ‘counter-reliefs’, adding wire strings) and Vasyl Yermilov, who lived Kharkiv in the 1920s. They continued the tradition of a collage-based polychromy in the aesthetics of what later became known as constructivism.

Although there is some knowledge about Archipenko’s works in post-Soviet Ukraine, there has been little, if any, reinterpretation and development of the wooden polychrome ideas, even within the informal visual art scene. However, it is a known fact that in 1952 Soviet authorities brutally removed nearly 2000 artworks from the Sheptytsky Museum (which was then called the Lviv Museum of Ukrainian Art), transferred them to a “special find” and subsequently destroyed these priceless pieces. Artworks of Alexander Archipenko were among those vanished artworks. At that time ideological directives of the Soviet authorities overseeing the art scene prohibited promotion and exhibition of art created by Ukrainians who lived and worked outside the Soviet Union. Only after Ukraine became independent, the understanding of Archipenko as a Ukrainian artist has gradually changed, sparking interest among the general public, and sculptors in particular. Such a shift became evident when a number of Ukrainian artists began actively using Archipenko’s ideas in their sculptures, as well as using the tendencies borrowed from his early avant-garde period.

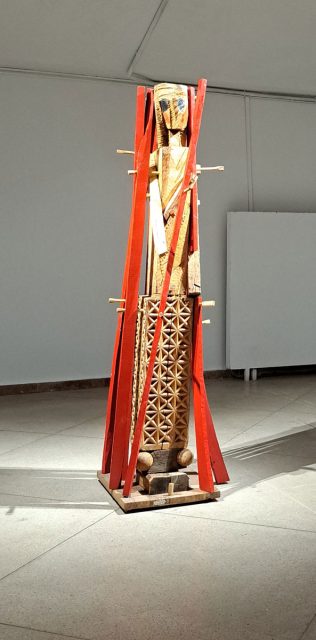

The reinterpretation of polychromy into the round sculptures and reliefs, the mastery which Archipenko has used throughout his entire creative life, has been vividly reflected in the works of Mykola Malyshko, a native of Dnipro region. Through decades he has consistently used wood as a material that deeply reflects the national roots of sculptural expressiveness. This includes combining hard textures with colour, very often black and bright red, and the expressiveness of openings, cesuras, and unfilled space as a geometric representation of movement.

Archipenko has been experimenting with the positive and negative space, using voids or apertures to give a greater visual expression to his forms right until the creation of “King Solomon” bronze figure in 1963, which he planned to turn into a monument. He wrote, “In 1912 […] I conceived a way to enrich the form by introducing considerable modulation of the concave. Its integral patterns become an inseparable part, which will be symbolically as important as the pattern of height. I applied this method to reliefs and three-dimensional figures […]. The combination of positive and negative forms has emerged as a new contemporary style”.

Ideas of apertures and the optical illusion of the concave part being perceived as convex have been consistently explored by Nazar Bilyk, a native of Kyiv, who uses new technological materials in exhibitions and in his monumental pieces.

Anton Logov, an artist born in Odessa, also explores these ideas, but in a different way. His installation “Reincarnation” for the exhibition project “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors” (2016) and “Trees of Life” (2020) for the landscape project PARK3020 represent hollowness as the element that prevents the decay of wooden fragments within a specific temporary structure.

It is extremely important that the private and state Ukrainian museums acquire Archipenko’s artworks. In 2019, the National Art Museum of Ukraine received a limited edition of his graphic sketches as a gift from the patron Igor Kryvetsky. They were printed in Berlin in 1921 and signed by the artist.

Several exhibitions from 2016 to 2021 included author’s casts of sculptural works owned by various private collectors, such as the “Blue Dancer” and “Nude”.

Before the full-scale Russian invasion Ukraine’s National Museum of Andrey Sheptytsky in Lviv showcased four Archipenko’s nude drawings which somehow miraculously survived the previously mentioned destruction. A copy of the “Woman Combing Her Hair” was exhibited at this year’s Sculpture Week at the Palace of Arts in Lviv.

Every year Archipenko’s art identity becomes increasingly more Ukrainian, while his artworks become an integral part of the history of Ukrainian sculpture in the 20th century. They also shape contemporary art tendencies. Despite the Russian invasion, various art managers in Ukraine still hold onto a dream of organising a major exhibition featuring Archipenko’s art.

* Archipenko in the Western Ukrainian Art Discourse. Publications and Reproductions from the 1920s and 1930s: A Reader, 2019.