According to Audit Chamber estimates, poverty rates have risen in 11 oblasts of Ukraine since the year 2000. Over 40% of the population in Volyn, Kirovohrad, Sumy and Kherson Oblasts, and around a total of 26.4% of Ukrainians live below the poverty line.

In contrast to European countries, the Ukrainian government is making the problem of poverty worse, rather than working to solve it. Its show of concern for the poor hardly improves the trend when the share of wages within the income structure is actually declining, while the share of social handouts is growing. In 2008, wages accounted for 43.3% of the total income of Ukrainians, falling to 40.9% in 2010. Meanwhile, with the resolutions it made in 2010, the Government has virtually ruined the wage scale and leveled out salaries in the public sector.

Over the past few years, the economic gap between oblasts and certain territories within these oblasts has widened greatly. In 1996, the maximum gross regional product (GRD) per capita was 2.7 times higher than the minimum GRD. In 2008, this gap grew to 6.3, and the current economic crisis has kept aggravating this trend. Even though, industrial production grew in most oblasts last year, it continued to plummet by 3 to 10% in Chernihiv, Kherson, Khmelnytskyi, Vinnytsia and Ivano-Frankivsk Oblasts, and by an appalling 22.2% in Chernivtsi Oblast.

Average salaries also vary significantly from region to region: in January 2011, Kyiv boasted 2.15 times higher average salaries than Ternopil Oblast, while the gap between Kyiv, Dnipropetrovsk and Donetsk Oblasts and Ternopil Oblast ranged from 1.45 to 1.7 times.

Salaries in Vinnytsia, Khmelnytskyi, Kherson and Kirovohrad Oblasts fell far below the average in Ukraine.They also have the highest percentage of employees paid below the subsistence level for the workforce. In December 2010,the percentage of such people was 3.8% in Kyiv compared to 4.5-5.2% in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, and 9-12.6% in Kirovohrad, Kherson, Khmelnytskyi, Chernivtsi, Ternopil, Sumy, Vinnytsia, Chernihiv and Volyn Oblasts.

Unemployment: from official to catastrophic

Official and hidden unemployment are the key problems of the economically depressed regions. Despite the recent sanguine projections of a slight decline of official unemployment in 2011 by Volodymyr Halytskyi, Director of the State Employment Office, in truth it has been growing 0.1% monthly since the beginning of the year, already exceeding 0.62mn, which is up 17% from last year. Average spell of unemployment is increasing, too.

The reasons for unemployment are also changing. The latest analytical report of the State Statistics Committee about the labour market in 2010 said that the percentage of employees laid off for economic reasons fell from 48.6% in 2009 to 43% in 2010 as Ukraine was recovering from the crisis. In contrast to this, the number of post-secondary school graduates who failed to find a job rose from 11.5% to 13.7%.

It comes as no surprise that the unemployment rate is higher in depressed regions than the average national rate, and it is almost twice as high as in relatively well-off regions. According to 2010 estimations from the International Labor Organization (ILO), unemployment reached 13% in Rivne Oblast and 10% in Chernihiv, Ternopil, Sumy, Cherkasy, Zhytomyr, Vinnytsia, Poltava, Kirovohrad, Kherson, Chernivtsi and Zakarpattia Oblasts, compared to only 6.7% in Kyiv and below 8% in Crimea, Dnipropetrovsk, Luhansk, Odesa and Kharkiv Oblasts.

Another striking gap is the numbers of jobless chasing every 10 available vacancies in different oblasts, reaching 293 in Khmelnytskyi Oblast, 259 in Cherkasy Oblast, and 139 in Vinnytsia Oblast, but only 34 and 37 in Dnipropetrovsk and Odesa Oblasts, and just 2 in Kyiv. The slight recovery from the crisis has not boosted demand for labour in most depressed regions, in fact, in 2010 numbers continued to fall in these regions while growing elsewhere.

Ukrainian officials frequently mention that the unemployment rate in Ukraine is supposedly lower than the average EU rate and several times below that of the most popular EU destinations among Ukrainian immigrant workers, such as Spain, Portugal and so on. If that’s the case, what makes huge numbers of Ukrainians head abroad in pursuit of work?

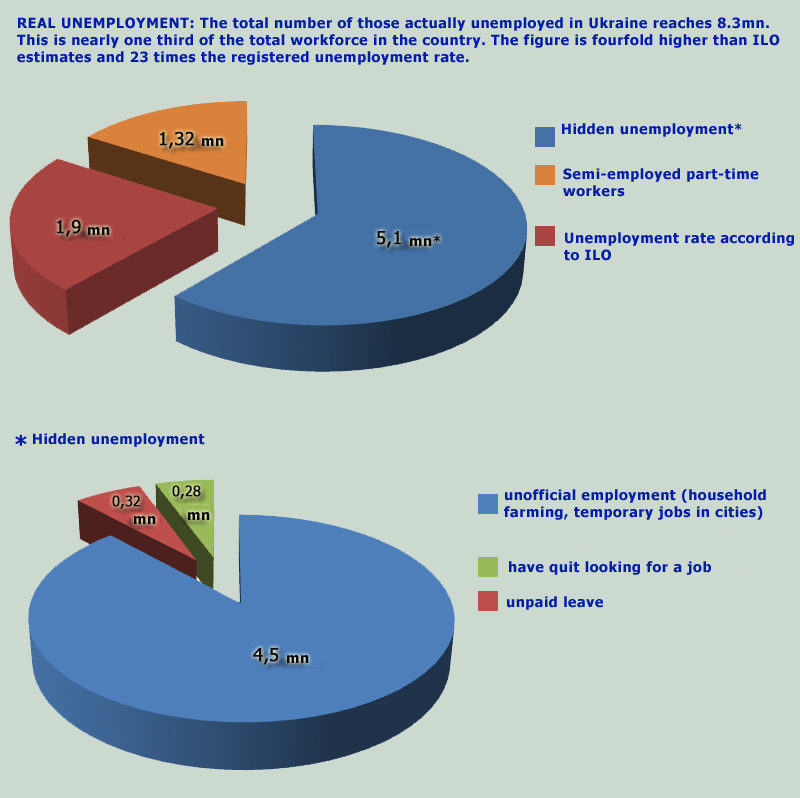

In fact, hidden unemployment is several times higher than even the ILO estimates. Out of the 1.9mn officially registered as jobless, 1.4mn are urban dwellers. The figure looks even more surprising given the fact that job scarcity is much worse in rural areas. One possible explanation is that the rural population employed in the unofficial sector qualifies as a special statistical category thus twisting the official indicator. These people spend their working lives trying to survive on their own domestic farming because they lack the skills and resources to switch to commercial farming, and anyway, the chances of finding a job are probably zero.

The lion’s share of those employed in the unofficial sector, estimated at 4.5mn in the first six months of 2010, lives in the countryside, including 2.3mn in villages and around 700,000 in towns which are regional centers. These 3mn people are mostly engaged in farming, while 1.5mn spend their time doing only temporary work. But probably the scariest fact in this whole situation is that 58.7% of those employed in the unofficial sector were rural youth aged between 15 and 24.

The second largest unemployment group includes people on unpaid leave (320,000) and those who have stopped looking for a job but do not qualify as unemployed under any criteria (280,000).

As a result, the total number of semi-employed Ukrainians is 5.1mn, and this an extremely optimistic estimate. The number includes nearly 1.32mn of those who have no other options but working part-time.

If we take into account the above mentioned figures, then total unemployment in Ukraine reaches 8.3mn, compared to the 1.9mn by ILO estimates. Hidden unemployment is 5.1mn and the number of semi-employed exceeds 1.3mn. 8.3mn is four times higher than the ILO indicator and 23 times the registered unemployment rate. In fact, one third of the entire workforce in Ukraine has no proper work, which explains massive labour migration.

Ukrainians as cheap work force?

Recently Serhiy Tihipko, the key reformer in the current Government and Social Policy Minister, ordered the State Employment Office to work out “a new employment strategy”. A closer look at this initiative gives the impression that its main purpose is to support employers who suffer from a shortage of professionals in certain areas because they offer uncompetitive salaries in the given region, rather than to overcome unemployment.

One of the points is to establish contacts with employers in various regions and move deficit workers there. If implemented, it is not hard to guess how these ideas will affect national and local unemployment figures. Over one year, the State Employment Office will arrange for the employment of 700-800,000 people. Even if every tenth worker moves to another region, their resettlement, including housing, will cost a fortune for the State Budget which will cover the labour migration program. For instance, almost half of all vacancies reported by companies over January – September 2010 were in Kyiv and its neighboring area, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast towns, and recreation areas in the Crimea, in all these places the cost of living is quite high. Nominal resettlement of just several percent of the jobless who cannot find work at home will have zero effect on the overall situation.

The jobless will unlikely be interested in moving without proper housing and salaries provided, and those who are ready for such radical steps are either looking for a job in Europe or will be soon.

Potential resettlement of the unemployed from depressed regions into better-off ones in the mid-term will not only put current problems on hold, but actually aggravate them further. Economic distortions will grow deeper, the housing issue in host towns will become more complicated, while real estate prices and rent will rise, pushing up the cost of living. Salaries for some categories of employees could be frozen as more working hands arrive and dilute the need to increase salaries. This will play into hands of big employers but provoke intolerance, especially among the regions and employees. Along with the resettlement idea, Mr. Tihipko is campaigning for the restriction of employees’ rights in favour of employers. He offers “to allow employers more flexibility and shorter deadlines in hiring workers on a temporary basis, and provide for a quicker procedure for firing them from such temporary work if necessary.”

No small business or foreign investors

Overcoming gaps in economic development among the various regions and dealing with official and hidden unemployment takes significant investment. However, total investment per capita in 2010 in Kirovohrad, Volyn, Rivne, Vinnytsia, Zhytomyr, Sumy, Chernihiv, Kherson, Zakarpattia and Ternopil Oblasts was between 1.5 and 5 times lower than the national average and Kyiv respectively. The situation will only improve if big investors, including foreign ones, grow more interested in these territories, or if the potential of small local businesses is used to the maximum extent. However, with the team in power promoting the interests of certain regions and export-oriented business groups on the one hand, and the tax war with small business and the neglected development of the domestic market on the other, the situation will only get worse.

Small business could serve as a potential reserve in overcoming unemployment. According to the State Statistics Committee, the trade sector was the most active employer in the first six months of 2010 with 5.8%, followed by personal services and the public sector. With the latter left out for obvious reasons, the industries dominated by small businesses could solve the problem. More than that, the role of small business is far more significant in some regions than throughout Ukraine on average, especially the industrial Eastern regions. In the first six months of 2010, the average national ratio of operating small businesses 661 to 10,000 people. Local ratios ranged from 505 in Donetsk Oblast, 569 in Luhansk Oblast, 830 in Mykolvyiv Oblast, 772 in Kherson Oblast, 766 in Chernivtsi Oblast, 712 in Khmelnytskyi Oblast, and 658 in Vinnytsia Oblast. The share of people employed in small business in Donetsk Oblast was 27.7% or 509,600 out of a total of 1.84mn wage laborers, compared to 28.9% in Luhansk Oblast, 31.4% in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, 39.6% in Chernivtsi Oblast (125,000 out of 316,000), 36.7% in Sumy Oblast, 36% in Kherson Oblast, 35.7% in Mykolayiv Oblast, and 34.7% in Khmelnytskyi Oblast.

The ratio of those employed in small business to other commercial entities looks even more striking. National average estimates demonstrate that more people are employed in big and medium sized business than in small, with 8.2mn and 6.5mn respectively. The gap is more visible in South-Eastern industrial regions, where the figures are 0.94mn and 0.51mn in Donetsk Oblast and 0.77mn and 0.45mn in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast. By contrast, the regions with the highest unemployment have the opposite ratio. Small businesses dominate in Ivano-Frankivsk, Zakarpattia, Khmelnytskyi, Ternopil, Rivne, Kirovohrad, Sumy, Volyn, Mykolayiv, Zhytomyr, Vinnytsia, Chernihiv, and Kherson Oblasts. In Chernivtsi Oblast, the number of those involved in small business is almost double the number of medium to big business employees with 125,000 versus 69,000.

All this indicates that the labour market and economic prospects in the above mentioned regions rely heavily on small businesses. The government’s attack on flat tax payers could very soon cause this trend reverse, turning small businesses from the major absorber of the jobless into a major creator of the unemployed. Especially now, since Serhiy Tihipko offered to introduce a system of indicative wages at small enterprises – yet another killer initiative after the new Tax Code. On 15 March, he made himself very clear: “I believe proposals from employers will not be taken into account.”

The government prefers to turn a blind eye to the unemployment problem rather than to start solving it. This makes the Party of Regions’ proposals to import a foreign workforce into Ukraine look so much more cynical. “We will invite people from abroad by the end of the year because we will lack the workforce. Not everyone today wants to work. Ukrainians have got used to fairly good unemployment benefits. They prefer to earn a little more by trading or doing temporary ‘side’ jobs,” says Oleksandr Stoyan, one-time Chair of the Federation of Trade Unions, and a Party of Regions Deputy today.

This “social policy” looks more like an intentional transformation of most Ukrainians into a cheap workforce.