Some four years ago Rinat Akhmetov’s role in Ukrainian business and politics raised no questions. He was the country’s richest entrepreneur, owner of a business empire with assets in virtually all sectors of economy, and a full-fledged stakeholder in the most influential political force, the Party of Regions. The PR’s iron grip on power seemed perpetual and Akhmetov’s influence was such that even his frenemies from the then president Viktor Yanukovych’s entourage, who had just started a large-scale redistribution of markets to suit their interests, would not risk an open conflict with “the master of the Donbas.”

The situation came to change with the revolution and war. The former sway of the Party of Regions lay in tatters. Bad news started to come in from economy. While the 100%-Akhmetov owned SCM Group is doing its best to restructure business, mining, metallurgy and energy remain the mogul’s main sectors. These are united under Metinvest and DTEK respectively. In 2014, as global metal, ore and steel markets began to shift, the prices went in a downward spiral.

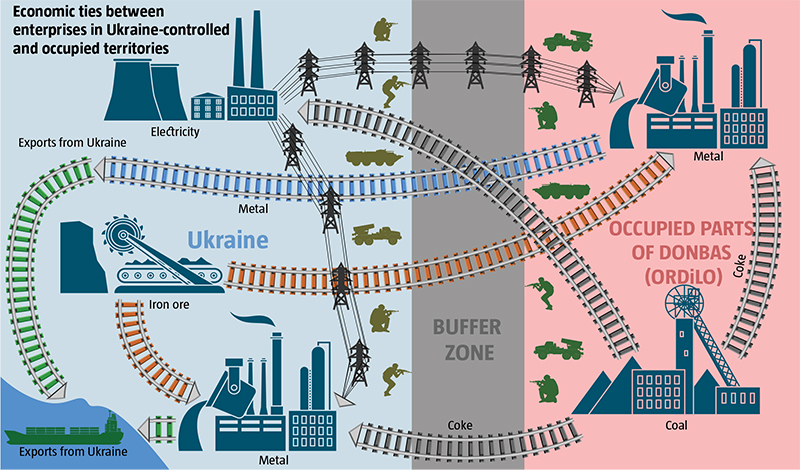

That was just the beginning of the problems, which were further exacerbated by hostilities. A large section of Metinvest and DTEK plants are integrated in a single production cycle. Explained in simple terms, coal from Akhmetov’s coalmines goes to Akhmetov’s coke and power plants. The output from these is shipped to Akhmetov’s steelworks, where iron ore from Akhmetov’s mines is already waiting. Then, all this is exported as metal and steel. Revenue in foreign currency is on the top of the pyramid. The splitting of the Donbas has complicated this scheme to say the least, as enterprises are located both on the occupied and Ukraine-controlled territories. For a while it caused substantial difficulties.

RELATED ARTICLE: How economic ties to the occupied territory of hte Donbas affects Ukraine's economy and de facto leadership of "DPR"/"LPR"

The proof can be seen in statistics dating back to the early months of the war. In the first half of 2014 Ukrainian enterprises were still producing 2.4 to 2.8 tons of steel per month. In August, when hostilities flared up and Russia made an open invasion at Ilovaisk, production plummeted by 28% to 1.7 ton. A number of steelworks were now on the occupied territory. The fact that in 2015 agricultural business ousted metallurgy from its leading position in Ukraine’s exports gives an idea of the scale of changes that took place during that period. Metallurgy had for decades been the main source of currency revenues for Ukraine. This status largely propped up the slogan “Donbas feeds Ukraine.”

In 2015, Metinvest reported total losses of $1bn compared to $160m revenue from the previous year. Along with the publication of the financial report, Metinvest announced a default in payment and initiated negotiations on debt restructuring with its lenders.

Luckily for Akhmetov, the dire situation began to look up. Early in 2015 the second Minsk Accords were signed, and the situation at the front stabilized. In April that same year growth in steel production was first reported, continuing into the following month, and the industry again returned to the figures above 2m ton per month.

Statistics show that good news came from commodity markets, too. Prices had stopped falling. According to Metal Bulletin, the price of iron ore almost doubled in 2016. The year saw also a growth in steel prices, despite the forecasts from experts on the market. After January to September 2016 Metinvest reported $989m EBITDA. Another sign of an improving situation is the beginning of investment in production. In particular, the Illich Steel and Iron Works in Mariupol invested over 1.6bn UAH in own production. On 30 January it was reported that the Metinvest mining and processing plants had paid 19bn UAH in dividends to the owners. According to the report, the shareholders’ dividends will be used “to serve the Metinvest debts and as part of capital investment in production facilities.”

In most cases, investments in production and debt payment are demanded by the lenders, who once agreed to restructure the Metinvest debt. However, the fact of such funding shows that the state of Akhmetov’s business is far from critical, in fact, it has fully adapted to the new conditions and is developing.

That a part of the production facilities are now on the occupied territories did not sever the links with them. Mines and metalworks are running like clockwork for the owner’s benefit, all thanks to the change of the facilities’ registered address. For instance, the Yenakieve Metalworks is now registered in Mariupol. By the way, the Russian owners of the Alchevsk Metalworks did the same and registered their firm in Siverodonetsk.

RELATED ARTICLE: What the January CabMin decree on the occupied territory means for Ukraine

The status quo after almost three years of war might look comical, if it were not for the underlying tragedy. Enterprises which are working virtually in occupation, but are nominally registered on Ukraine-held territories, duly pay taxes to the state.

According to the SBU, in 2016 they paid more than 31bn UAH, of which 777,445,908.57 was the military tax providing for the needs of the Ukrainian Army. Moreover, Energy and Coal Minister Ihor Nasalyk says that 50,000 mineworkers from the occupied region are legally employed on Kyiv-controlled territories, where they also receive their wages. These have paid 1.9bn UAH in taxes.

Meanwhile Ukraine’s government has failed to introduce transparent rules in the matter of trade with the occupied regions. The “smuggling in Donbas,” which has become a staple item in the news, does not in fact break any laws. Instead the only ones who are effectively punished for contraband are the ordinary inhabitants of the occupied regions who smuggle relatively small amounts of food.

“When I worked in Luhansk oblast, I had trouble explaining why a person may not carry 100 kg of cheese in the boot of his car, while border guards detained a freight car with electronic devices and all the necessary papers on the way to the occupied territories. I could not fathom it. Nor could I understand how to explain this to the border guards, from whom I demanded compliance with the restrictive orders. They did not understand it either. Because there is not a grain of logic to it,” said the former head of the Luhansk Oblast State Administration Heorhiy Tuka in his interview to The Ukrainian Week in September 2016.

Coal has become the addictive injection which captured the Ukrainian government giving it an argument against the blockade of the occupied territory to throw in the face of the voters. The country has 12 co-generation stations or thermal electro stations (TESs) running exclusively on high grade anthracites which are not mined on the Ukraine-controlled territory. The electricity produced by those TESs is not only consumed by industry, it is also used to light and warm homes. According to minister Nasalyk, Ukraine is working on the diversification of supplies and re-equipment of the facilities so they can use other fuels. In particular, a pilot project is already launched at the Zmiivska TES. However, over these three years the government has failed to fully cover the country’s need in energy without anthracite.

“Should the ATO zone be totally cut off, we will have to resort to rolling blackouts. There will be a certain adaptation period. We have developed a schedule. The current supplies are sufficient to last roughly through the end of March,” said the minister. He added that the shipping time to get anthracites from Australia, South Africa, China, or the US (the countries producing this type of coal) would be 50 to 55 days. This should be the period when rolling blackouts would be applied.

RELATED ARTICLE: How Ukraine's oligarchs affected the economy before the Maidan

Most TESs in Ukraine are private property. Nasalyk claims that the government negotiated with the owners, but to no avail.

“It is very hard to force a private owner into doing things. Besides, it involves significant costs. If the reconstruction of the Zmiivska TES cost us 240m UAH, the bill for re-equipping Block 7 at the Sloviansk TES will stand at 500m UAH or even higher. The majority of owners insisted on reconstruction costs to be incorporated in energy prices, so that they might compensate the costs. But there is no room to raise the prices any further,” said he at a press conference on 7 February.

Out of the 12 TESs running on anthracite only three belong to Akhmetov’s holding: the Luhansk TES in Shchastia and two in Kryvyi Rih and Dnipro. Yet there is solid evidence that they consume the most anthracite imported from the occupied territories. In March 2016 the Ukrainian Cyber Army, a hacker group, reported hacking into mailboxes of the so-called transport ministries of the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk “People’s Republics” (in fact, the facilities of the Donetsk Railways on the occupied territories). According to their data, most coal containers from the occupied territories went to those particular TESs: 2,203 freight cars (132,000 ton) to Shchastia and 4,452 cars (267,000 ton) to the facilities of the DTEK Dniproenerho (which includes the TESs in Kryvy Rih and Dnipro). That very month coal was also shipped to six more TESs, but the total of only 3,741 freight cars is almost the half of what was shipped to Akhmetov’s three facilities.

A self-fulfilling prophecy here is that not only big investment costs, but the structure of the business hinder the re-equipment of energy-producing facilities. For Akhmetov, tycoon and owner of TESs, giving up anthracite would mean giving up his own profits. In the meantime coal production on the occupied territory grew considerably over 2016: DTEK Rovenky Anthracite increased anthracite production by 43% last year, up to 2.2m ton, and DTEK Sverdlov Anthracite by 30%, up to 2.3m ton.

Even three years after the change of government Ukraine’s richest business owner still holds sway over politics in the country. His business is virtually adapted to the current “neither war nor peace” situation. Regardless of personalities, any tycoon’s money loves silence and once adapted, a business is least interested in serious change. Since the stabilization of the division line in Donbas, stable financial flows and commercial routes have come into being. Changing this would be probably the trickiest task for Ukraine’s government, if the de-occupation of Donbas is really a priority. Since the Minsk Accords were signed, more than 400 civilians and 500 troops have been killed there.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook