On November 17, 2011, Ukraine’s “Election of National Deputies” law was passed.Both the ruling factions as well as the opposition voted for it, including 62 MPs from Yulia Tymoshenko’s Bloc (ByuT) and 32 MPs from the Our Ukraine – People’s Self-Defense bloc (NU–NS). Having achieved its goal, the regime is satisfied. The opposition was able to bargain for some procedural improvements, but in practice these will be of little help to them.

THE MYTH OF VICTORY

Despite assurances by opposition members that the passing of this law involved consensus and compromise, there are good reasons to believe that the regime has won an outright victory in the fight for election rules. The text of the bill was handed out to MPs right before the vote, which was finished in record time—less than an hour—leaving virtually no time to analyze the final version. Thus, given our parliament’s long-lasting traditions, we can ascertain that a political choice was made behind the scenes by certain opposition members following negotiations with top government officials.

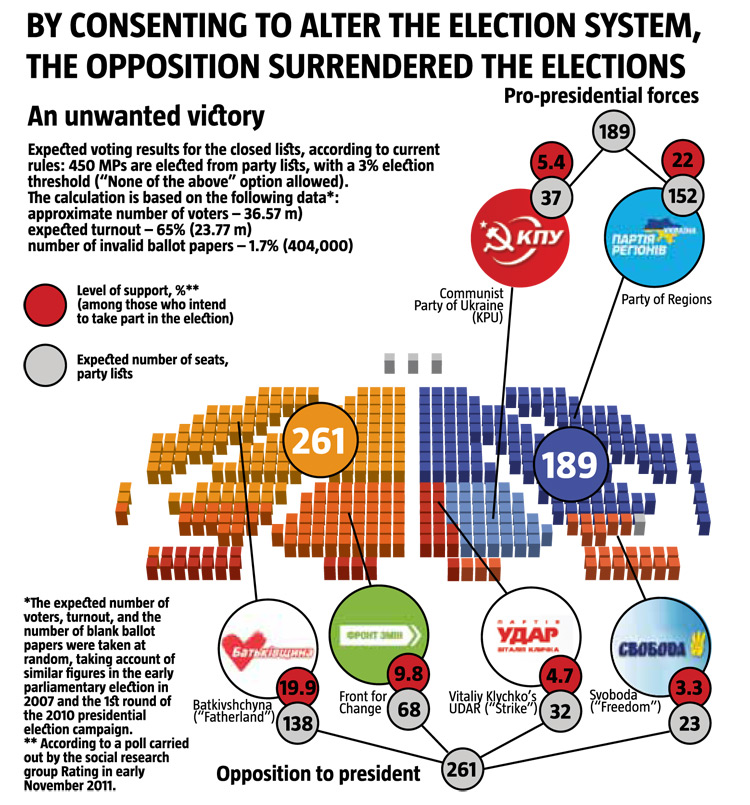

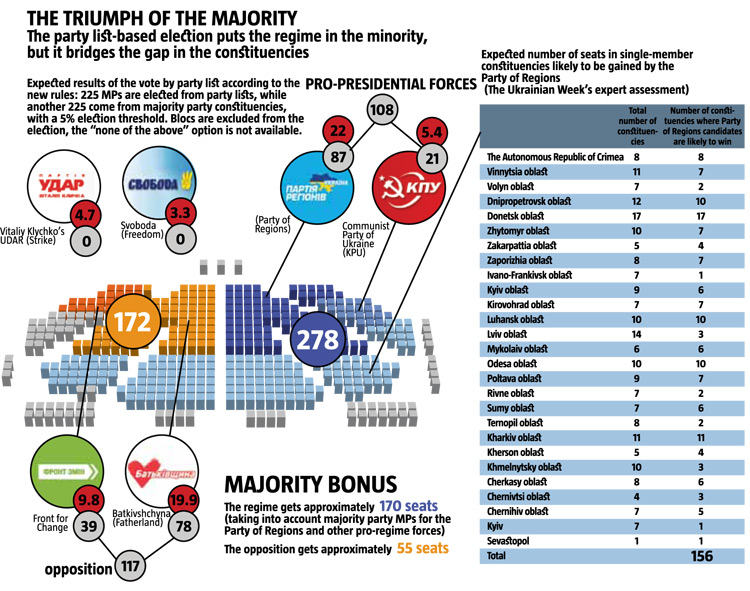

The gains from this decision were distributed accordingly. Of course, the ruling regime got the lion’s share. The law preserves chief provisions upon which they will rely in achieving a majority in the next parliament. First of all, this means winning half of the parliamentary seats in by simple plurality vote for specific candidates, enabling loyal people to be elected by means of administrative and financial resources—a situation analogous to the 2002 parliamentary election and 2010 local elections. It’s no wonder the Venice Commission insisted that under current conditions, Ukraine’s mixed system jeopardizes election fairness.

Secondly, despite the campaign promises of virtually every major party, the revised law retains the use of so-called closed candidate lists, i.e. those formed by political leaders. This means that seats will continue to be sold. Those who buy such tickets to parliament will feel free from any obligations to their “own” party. Thus, the next convocation of the Verkhovna Rada will see more faction defections.

Raising the election threshold in addition to banning blocs would not merely curb the number of political forces that can be elected to Parliament. The higher the threshold, the more seats can be distributed as bonuses among the parties that successfully get past. This is just another reason that the November 17 vote for the election law is being labeled “a conspiracy against small parties.”

Finally, the regime has won an important moral victory. The new election law, approved by 366 MPs, does not appear to have been imposed by the majority. In fact, by supporting it, the opposition legitimized in advance both this document and the violations it allows. Thus, Europe’s future claims concerning foul play in campaigning and elections will be voided by an iron argument: the opposition itself supported this election legislation. This is exactly why its active participation in the vote was needed. The majority alone would have had the minimum 226 votes necessary to pass the law, but its legitimacy would have been less certain without minority support.

Ultimately, the “barriers against violations” supposedly included in the law by the opposition will be easily evaded. Even though the procedure for forming election committees has changed, the Party of Regions can easily secure a loyal majority in the committees by reanimating various puppet political projects. After all, representatives of Batkivshchyna, NU–NS, and other opposition forces are very likely to change their political orientation once they are appointed to the committees. The arsenal of coercion is well-known – administrative resources, graft, and intimidation. All this will effectively whittle down the “democratic amendments” to the election law.

What’s the use of the parties’ right to revoke defecting members of an election committee? This doesn’t happen automatically: the party has to appeal to the relevant committee to recall its representative. Yet at any stage of the election process, a higher level committee has the right to supersede a lower one. Thus, the Central Election Committee (CEC) can act on behalf of a district committee, while a district committee can supersede a local committee. This means that higher-level committees can delay decisions concerning replacement of election committee members following an appeal by an opposition party.

And what about the medical certificates required in order to vote from home? Medical institutions are totally subordinate to state and local governments, making the procurement of limitless certificates as easy as pie.

Thus, the 2010 local elections, based on the same model, demonstrated that the combination of legislative preference for the regime, coercion, and result rigging will lead to a disproportionate presence of pro-regime forces in the parliament.

THE OPPOSITION’S USUAL PROBLEMS

Given these obvious issues, why then did some opposition forces (namely, BYuT, paralyzed after Yulia Tymoshenko’s incarceration, and Arseniy Yatseniuk’s Front for Change) agree to such collaboration? The answer partly lies in the “big parties vs. little parties” conspiracy.

However, many of the opposition MPs and faction leaders are veteran politicians. This “conspiracy” appears too inadequate a deal for them to collaborate with the regime. Thus what remains is a kind of private agreement between Tymoshenko’s bloc, the Front for Change and the regime. Illustrative in this respect are reports of lively consultations on the bill held by Vice-Premier Andriy Kliuyev. More details concerning these arrangements will become evident in the near future: as the state turns a blind eye to the activities of certain companies associated with the BYuT and Front for Change; as these political forces launch their campaigns in territories which will serve as a springboard to the Verkhovna Rada; or as active negotiations resume between various groups in the government and opposition (for example, between Rinat Akhmetov and Yatseniuk, as the media have reported).

By taking part in such arrangements to secure personal benefits, opposition leaders have effectively agreed to a secondary, subordinate role and risk suffering a strategic defeat. Such subordination, the perhaps unconscious need for a senior partner who is at once a target for criticism but also a source of benefits in exchange for certain services, has long plagued our opposition. The developments of recent years have somewhat obscured certain servile moves by the Our Ukraine party, a faction of which is now attracted to Yatseniuk’s party. For instance, Our Ukraine voted for Yanukovych’s government program in April 2003, giving then prime minister Yanukovych an additional 335 votes and allowing him to claim the support of a “constitutional majority” and ignore the opposition’s demands for legislative support. Another more vivid example is the vote that led to the privatization of the UkrRudProm mining association in April 2004. Only Our Ukraine’s support allowed that decision to get the necessary 226 votes. As a result, metallurgy was monopolized by several oligarchs who now sponsor the Party of Regions, among them Akhmetov.

Tymoshenko’s bloc is also given to backstage deals. Before her incarceration, Tymoshenko always pursued her own policies and at least did not allow her faction to be used as a pawn. Without its leader, however, the BYuT can become a source of votes for the regime’s dubious initiatives, in exchange for favors for other leaders who are still free. In this context, the imprisonment of the former prime minister, despite protests from the West, gains a cynical but viable practical explanation.

DO YOUR BEST

Thanks to this new legislation, it is now virtually impossible to prevent mass election rigging. But this does not mean that the opposition has to resort to its favorite pastimes of infighting and bemoaning lost opportunities. Recent statements indicate that a fraction of the opposition will never collaborate with the regime. Thus, there is a force that should ensure maximum transparency of the election process. Or, to put it more precisely, reduce violations to a minimum and carefully record episodes of fraud. Such records can provide support for well-grounded conclusions about the illegitimacy of elections – if the opposition is even motivated enough to defend the actual will of voters.

Here, the crucial issue is the formation of electoral committees. A true opposition should coordinate its effort to man committees (on both district and local levels) with competent, experienced individuals with good reputations and aversions to bribery and rigging. Such people are far more effective than so-called “experts in electoral procedures.” It is already high time to start registering and training the people who will be delegated to election committees. It would be sensible to create a special coordination center for this among true opposition forces.

Such a center could also train and coordinate the activities of observers and other individuals who have the right to be present at election committee sessions and polling stations, such as candidate MPs, their proxies, authorized party representatives, and journalists. The next key issue for the opposition is ensuring expert training for observers and their even distribution among election committees and polling stations.

The presence of international observers at the 2012 election should become a special concern for the opposition parties. International monitoring of polling stations and election committee sessions, with the possibility of photo and video records, is a serious factor in reducing election fraud. That is why the opposition should send a collective appeal to the EU, Council of Europe, OSCE, and other international organizations and democratic powers requesting them to consider sending official observers to monitor the upcoming parliamentary election in Ukraine. Monitoring will only be effective if there are at least five to six thousand international observers in this country. In order to provide interpreters, the true opposition must now begin looking for competent speakers of foreign languages among its supporters.

Special attention should be given to the counting of ballots at polling stations. We cannot rule out the possibility of using this practice when election committees ban candidate MPs, their proxies, and official observers from polling station premises on the grounds of alleged “illegal interference” with the session. With witnesses removed, the pro-regime committee can easily void ballots cast for opposition candidates, or rig the vote in other ways. To prevent this, the true opposition should place supporters outside polling stations after voting ends at 10pm, and also create a reserve pool of accredited journalists and official observers with the right to be present at polling stations.

Another item on the agenda is the parallel counting of votes. This should not be a small-scale, amateurish “parallel count” by one party. Rather, it should be a large collaborative multi-party project carried out by the opposition’s “Central Election Committee” on the basis of reports issued to local election committee members, with replicas issued to observers. Maximum transparency of the parallel vote count and media involvement in the process can reduce the risk of electoral fraud at polling stations.

The opposition parties must, on one hand, ensure the transparency of their election campaign and, on the other, persist in counteracting violations on the part of the regime. In doing so, they will have to overcome hurdles which they themselves helped to build by supporting the election bill. If the opposition fails to do this, its activities in Ukraine will be largely marginalized after the parliamentary elections in October 2012.