In the national memory of Ukrainian citizens, the hunger strike of 1932-1933 takes the shape of a continuous plague of starvation. In fact, it is necessary to make a distinction between the famines caused by a) the grain collections of 1930-1931 and b) the punitive action of the last quarter of 1932 and first half of 1933, which its initiator Joseph Stalin called "a crushing blow against the Whites and Petliurites" in November 1932.

Ukraine, more than other regions, resisted the total collectivisation of agriculture, which began with communal farms. This is evidenced by the statistics on anti-Soviet uprisings. In March 1930, Stalin was forced to pause collectivisation for six months before continuing it in the form of artels [cooperative associations], i.e. collective farm workers were allowed to own their own subsistence farms. Punishing the peasants for their resistance, he imposed unsustainable grain procurement plans, which were implemented through requisitions, on Ukraine from 1930. Confiscations from the 1931 harvest resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of Ukrainian peasants from hunger in the first half of 1932. However, the ultimate goal of Stalin's terror was still not to murder an indefinite number of them so that the rest would be forced to obey. On the contrary, the authorities tried to reduce the death rate by stopping exports and even importing small shipments of grain.

In January 1933, Stalin (as Lenin did in March 1921) replaced the surplus appropriation system with a food tax, which halted the imminent collapse of the agricultural sector. At the same time, he struck "a devastating blow to the White Guards and Petliurites" in Ukraine and the Kuban. This punitive action consisted of four elements: the confiscation of all non-perishable food, stopping peasants from leaving their places of residence, an informational blockade and food aid through collective farms and state farms during the 1933 sowing season. In the last months of 1932, the mechanism of this "devastating blow" was tested in the collective farms and villages that had been put on "black boards" of shame for not fulfilling the grain procurement plan, and at the beginning of January the confiscation of all food spread throughout the territory of Ukraine and the Kuban.

The essence of the "crushing blow" was the deliberate creation of conditions incompatible with life. Both the national intelligentsia and the church were hit by the Stalinist terror. However, the Ukrainian peasantry suffered the most. Expanding the preventive repression, Stalin used Lenin's experience of curbing anti-Soviet uprisings. The origin of this "crushing blow" is linked to confrontation between the authorities and the peasantry on the cusp of 1920 and 1921.

Leninist Surplus Appropriation

Lenin banned free trade between rural and urban areas, introducing centralised food distribution for the urban population and Red Army through the forced seizure of peasant produce. Not wanting to give away the fruits of their labour to the state for next to nothing, the peasants reduced grain crops to a level that only satisfied the needs of their own households. In response, the state requisitioned this produce intended for consumption by the peasants, condemning them to starvation.

Ukrainian peasants offered the most serious resistance against the prodrazvyorstka [surplus appropriation] policy. The countryside was replete with weapons leftover from the war. When Lenin tried to supplement the confiscation quotas with similar targets for sowing, in order to prevent the catastrophic decay of agriculture, the peasants showed their readiness to turn these weapons against the Bolsheviks. The Russian government treated the suppression of the rebel movement as a major military campaign. About a million bayonets and sabres in six armies were posted in Ukraine in 1920. The Kremlin mobilised its most capable units in the struggle against the rebel movement, which the Bolsheviks called "kulak banditry". The use of a regular army against the peasantry called all the Bolsheviks' previous Civil War successes into question.

Eliminate Makhnovism. The 1921 famine was one of the most important causes behind the crisis inthe insurgent movement in the south of Ukraine

The authorities were unable to cope with the peasantry. Here is a sketch taken from a telegram to Lev Trotsky from Mikhail Frunze on 13 February 1921: "The main cause of the crisis is the complete paralysis of transport in Ukraine. All the shipments are on the road – barely anything gets to front-line bases or the barracks. The garrison in Kharkiv is regularly starving."

Military commander Frunze could have assumed that the root of the crisis was the collapse of the transport system. However, it was caused not by a lack of coal on the railways, nor by a lack of bread in the mines. These were the consequences of a ruin that gripped all sectors of the economy as a result of the breakdown of trade links between the city and the countryside. Lenin finally understood the danger of a war with the peasantry. In March 1921, he replaced the confiscations with a prodnalog [food tax]. This is how the New Economic Policy (NEP) was started.

Grain Collections during a Catastrophic Drought

In 1921, a catastrophic drought occurred in the main grain-producing regions – the Volga region, Northern Caucasus and the southern provinces of Ukraine. Its devastating effect was combined with the damage to farmland in Ukraine as a result of seven years of almost continuous military action. The decrease in the amount of crops sown due to the surplus appropriation policy also affected the harvest.

What was the grain harvest like in 1921? Ukrainian and Russian statistics differed fundamentally. The Central Statistical Directorate of the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic estimated the harvest at 633 million poods [an Imperial Russian unit of measurement equivalent to around 16kg], while its Ukrainian counterpart gave a figure of 277 million. At the 7th All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets (December 1922), People's Commissar for Land Affairs Ivan Klymenko mentioned a significantly smaller number – 200 million poods.

The dispute could be resolved by checking the statistics at source. Why did not the Ukrainian government not make arrangements to do this, knowing that Moscow would insist on taking the maximum amount of grain? On 18 May 1921, Vladimir Lenin sent a telegram to the head of the Ukrainian government, Christian Rakovskiy: "It is a matter of life and death for us to collect 200-300 million poods from Ukraine". Rakovskiy did in fact make arrangements just prior to the harvest season. On his proposal, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Communist Party adopted the following resolution on 11 June: "Suggest that the Provincial Committees monitor the People's Commissariat for Land Affairs, the People's Commissariat for Food and the Statistics Bureau to ensure they regularly send information about the harvest once a week." Not stopping there, Rakovskiy approved a decree for commissions to go on fact-finding trips to provinces that had a bad harvest in order to discover the true state of affairs in agriculture. However, this decree, on instructions from central leadership, was cancelled by the Ukrainian Central Executive Committee, as Rakovskiy later stated, "for purely political reasons – not to create panic".

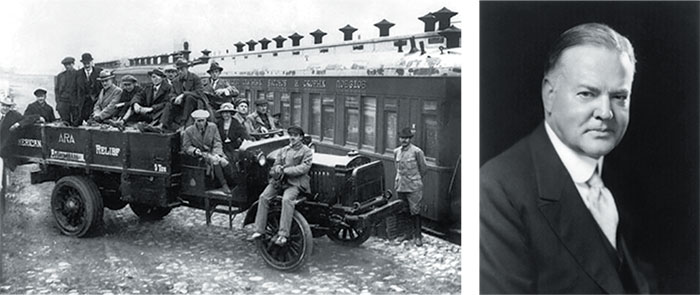

International aid. The American Relief Administration (ARA), headed by Herbert Hoover, was only allowed to enter Ukraine in 1922, when it had already been active in the Volga Region for six months

The amount of food tax that Ukraine had to pay from the 1921 harvest was approved as117 million poods and the republic was also obliged to repay its debt from the 1920 allocations – a total of 171 million poods of grain. The winter confiscations started slowly. In January 1921, the Russian Federation received 142,000 poods of grain and another 247,000 in February. In March, when armed brigades of workers were sent to the countryside, supplies to Russia increased to 1114 thousand poods, but in April again fell to 132 thousand. With the help of armed force, it was possible to send 522,000 poods in May. However, Ukraine did not fulfil its supply plan for May and Rakovskiy was reprimanded by the Party for his "insufficiently vigorous work".

In July, the harvest in the South of Ukraine began alongside food tax collection. The peasants firmly resisted the state purchasing agents who tried to take away their meagre harvest. In the beginning of July, Lenin got involved in the collectionof food tax. He suggested "mobilising around 500,000 bayonets from the youth of the Volga region and posting them in Ukraine to help them to enhance farming work, as they are very interested in this and have an especially clear understanding and feeling of the unfairness of rich peasants' greed in Ukraine". It was technically impossible to realise this insidious plan due to the complete disorder in the starving region. The Volga peasants themselves left the area affected by drought and headed to other regions on foot, as the railways were paralysed – 439 thousand refugees found shelter in Ukraine. They were taken care of by the Central Commission for Assisting the Starving, which was established in July 1921 by the Ukrainian Central Executive Committee.

The situation in the south of Ukraine was no less tragic than in the Volga region. In 21 counties in five provinces (Odesa, Mykolaiv, Katerynoslav, Zaporizhzhia and Donetsk), peasants were unable to reap what they had sown. In 10 other counties, grain harvests did not exceed 5 poods per capita. This amount was only enough to avoid death from starvation.

25 counties in Dnieper Ukraine collected from 5 to 10 poods of grain per capita in 1921. In order to cover the previous year's allocations and pay the food tax in kind, the peasants of these counties gave the state a significant portion of their own food supply. In 46 counties of Dnieper Ukraine (25 left-bank and 21 right-bank), i.e. half of the republic's territory, the net harvest of grain exceeded 10 poods per capita for the rural population. However, the amount of cultivated land there had been decreased due to the surplus appropriation programme. Even in the best of times, these counties did not provide a large marketable surplus of grain, and now they were expected to replace the drought-affected main areas of commodity farming.

These scraps of grain from half of the republic's territory were not enough to support the army, the cities and workers' settlements, refugees from the Volga region, the cities of Central Russia, the starving Volga region and Ukraine's own five poor provinces. In this situation, Moscow developed its own system of priorities. The Russian government ensured minimal, sometimes starvation, rations for the working class and army, as well as making some arrangements the Volga peasants. But the Kremlin tried to forget about hungry Ukrainian peasants. Newspapers were banned from covering the situation in the southern provinces of Ukraine. On 4 August 1921, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Communist Party adopted the following resolution: "Instruct the provincial committees that during the campaign it is necessary to distinguish between calls to fight hunger in Russia and to fight crop failure in Ukraine, where assistance to areas affected by the bad harvest can be provided entirely from their own provincial or county resources".

What kind of assistance did this refer to? On 12 August, Lenin signed a decree of the Council of Labour and Defence on applying extraordinary measures when collecting the food tax, which foresaw that military units should be sent into parishes and villages that made a stand against the state purchasing agents. Troops were to "take the most coercive measures possible" when collecting the food tax in kind.

Accompanied by troops, the state collection agents invaded the starving provinces. In particular, in Voznesensk County, they had instructions to "take 15 to 25 hostages from the kulaks and middle class in each parish. In the event that a village refuses to give a signed acknowledgement of their mutual responsibility, or does not pay the food tax within 48 hours of signing, it will be consideredan enemy of Soviet rule. Half of the hostages should be sentenced to the maximum punishment – the firing squad, after which the next group will be taken."

Local authorities could not understand the reasons behind the government's inaction in the fight against hunger in the southern provinces, as well as the introduction of an information blockade. On 30 January 1922, the Donetsk executive committee sent a telegram to Kharkiv: "Famine in the Donbas has taken on horrific proportions in the Mariupol, Hryshyn, and Taganrog districts. Up to five hundred thousand people are starving. In their despair, peasants are digging their own graves and cannot perceive any real help. So far, no a single grain has been received from the authorities." At precisely this time, Lenin informed the local authorities that a three-month supply of grain had been delivered to the Donbas to support the coal industry. Nevertheless, it was supplied to the mines, not the villages. On the contrary, the villages of the Donetsk Region had their grain taken away. By 15 January 1922, 120,000 poods of grain had been pumped out of the province.

Foreign Aid

Despite the ever-increasing threat to the lives of millions of people, the Bolsheviks did not seek help from the international community. It was the rest of the world that contacted Soviet authorities as soon as it learned about the catastrophic drought. In early July 1921, scientist and public figure Fridtjof Nansen made an offer to the Russian People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Georgy Chicherin, to help the population of Petrograd. Then Herbert Hoover, head of the American Relief Administration (ARA), got in touch with the People's Commissar. This non-governmental charity organisation had been active in Western Europe since 1919, using the huge food supplies that the American Expeditionary Forces left behind after the war.

Lenin was forced to consent, although he did not like the idea of bourgeois aid. In order to balance out the class structure of the foreign aid, he got Comintern involved. This is how Workers International Relief emerged. Starting on 20 August, a large ARA charity campaign was launched in the Volga Region.

However, these foreign rescuers were not invited to Ukraine. Nevertheless, the republic was swarming with departmental and territorial aid commissions for the starving. Their activities were directed towards the Volga region refugees in Ukraine. When hundreds of thousands of peasants in the southern provinces began to die from hunger, Ukrainian Bolsheviks were against keeping silent about the tragic situation. During discussions on the Central Committee report delivered in December 1921 by Rakovskiy at the 6th Ukrainian Communist Party Conference, Mykola Skrypnyk said, "Was it not obvious that we were heading for famine? The Central Committee put off this issue. Week after week, month after month, and only now can we clearly see the error discovered here. We did not dare say at the time that we had a faminein our blessed Ukraine." At the same time, the 7th All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets was taking place, where Hryhoriy Petrovskiy presented a report from the Central Commission for Assisting the Starving. Forced to try to extricate himself, he gave this sophisticated explanation: "In Ukraine, due to the more favourable harvest in the previous year, the acute food shortage only made its presence felt from late autumn, despite the similar influence of the drought on the 1921 harvest as in the Volga region. Before the winter of 1921, the same horrible and blood-curdling nightmare as in the Volga region hit the steppes of the federation's breadbasket, with the same terrible and frighteningvariety of sceneson display."

Petrovskiy was seconded by Rakovskiy. In a secret letter to Lenin dated 28 January 1922, he put emphasis not on the "error" that Mykola Skrypnyk had mentioned, but on a "crime": "I muststate that we have discovered criminal negligence with regard to the food and sowing requirements of our starving provinces. […] This was due to the fact that above all we were focusing on Soviet Russia and the Donbas."

The leaders of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic put forward various reasons for this "criminal negligence". Hryhoriy Petrovskiy pointed out the presence of large stockpiles from the previous year's harvest in the southern provinces of Ukraine, while Christian Rakovskiy referred to the government's priority of Russia and the Donbas in its concerns about the starving. However, these facts have nothing to do withthe huge death tollin the Ukrainian South, which reached almost 900 thousand people, according to the very approximate estimates given by Oleksander Hladun in his study (Essays on the Demographic History of Ukraine in the 20th Century, Kyiv, 2018).

Indeed, how can the difference between estimations of the 1921 harvest by the Russian and Ukrainian statistical authorities be explained? How can the ban on verifying the real state of affairs regarding crop yields in the southern provinces of Ukraine be explained? How can the draconian methods of confiscating grain for the food tax in provinces affected by a catastrophic drought be explained? How can the information vacuum about starving Ukrainian peasants that continued until 16 January 1922 be explained? On that day, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Communist Party instructed its propaganda and activism department, as well as the Central Commission for Assisting the Starving, to take measures to ensure that "as much as information as possible about the famine in the South of Ukraine" appeared in the press. The newspaper Communist was ordered to send a correspondent to the starving provinces in order to cover the situation there.

And, finally, the main thing: how can it be explained that access to the southern provinces of Ukraine was denied to foreign charitable organisations during the second half of 1921, when hundreds of thousands of men, women and children were dying terrible deaths there? Organisational efforts or material resources to radically correct the situation were not required from Kremlin leaders. All that was needed was their goodwill. However, only on 10 January 1922 did Rakovskiy managed to conclude an agreement with the ARA similar to the one signed by the Russian government in August 1921.

An Answer to All the Questions

Soviet historiography did not deny the presence of anti-Soviet uprisings in the part of Ukraine ruled by the Bolsheviks. How could it when Soviet rulewas stamped outin the middle of 1919 more by widespread anti-Soviet uprisings caused by the surplus appropriation policy and the aspirations of the Bolshevik leadership to impose communes on the villages than anyattack fromthe White Guards? How could one gloss over the presence of Nestor Makhno's powerful army in Ukraine, which fought against all political forces and their armed formations, but from time to time made agreements with the Bolsheviks?

In the report of the Ukrainian government at the 5th All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets, it was argued that more was done in 1921 to "pacify" the countryside than during the entire prior period. The All-Ukrainian People's Commissariat provided the relevant statistics: 444 atamans [Cossack chiefs] were taken out of action by various means during the first 10 months of the year –189 were killed in combat, nine were executed by firing squad, 84 were arrested and 162 surrendered voluntarily and were pardoned. Most of those who turned themselves in did this in the second half of the year. Why was this the case?

Soviet historiography responded that the rebel movement began to decline when peasants felt the beneficial influence of the new economic policy. However, grain procurement methods did not change even against the desperate backdrop of that famished year. The more convincing explanation lies in the experience of Nestor Makhno's campaign. Pursued by the cavalry and armoured units of the Red Army, the Makhnovists gathered for discussions on 21 July 1921 in the village of Isayivka, Taganrog County. It was discussed in which region the struggle should be continued. "Father" Makhno tried to change region from one that was familiar but dangerous due to the concentration of troops and launched a raid on the Donetsk and Volga steppes. But in the context of the approaching famine, the political activity of the peasantry fell to practically nothing. Without support from anyone, Makhno was forced to turn his tachankas [horse-drawn machine guns] westwards. He first crossed the Dnieper and then the Dniester before going into exile in Romania.

Lenin considered the natural cataclysm that struck the rebellious Ukraine his best ally in suppressing "kulak banditry". In order to intensify the starvation, peasants in the southern provinces had their last grain taken away to pay the food tax. Foreign charitable organisations were not allowed in Ukraine, so that the hunger would continue and take away human lives. A hungry peasant could not resist against the authorities. For the first time, the Bolsheviks added punishment by starvation to their multicoloured terrorist palette.

Foreign aid continued from March 1922 to June 1923. In August 1923, when foreign organisations had fully established their operations in Ukraine, they were feeding 1.8 million inhabitants of the provinces where the harvest had failed, compared to the 400,000 that were supplied by the Party-linked Central Commission for Assisting the Starving. Consequently, the role of foreign organisations was decisive. The contemporary press greatly embellished the role of international proletarian solidarity. Conversely, the importance of the ARA and other "bourgeois" organisations was diminished. However, statistics set the record straight: while they were operating in Ukraine, Workers International Relief supplied 383,000 rations to the starving, while Nansen's mission and the ARA distributed 12.2 million and 180.9 million respectively.

In 1922, 2.7 million dessiatins [Imperial Russian unit approximately equivalent to 11,000 square metres] less than in the previous year were sown in Ukraine. Huge shortages in the southern provinces due to the economic ruin of the peasants were partially covered by an increase in cultivated land on the Right Bank and Left Bank of the Dnieper. However, the republic was forced to deduct more than 10 million poods of grain for export from the 1922 harvest. This is a small amount, but even that could have alleviated the situation for starving people. Moscow ordered the Ukrainian leadership to restart the grain exports that had been interrupted by war in order to obtain foreign currency. Both the export of grain and supplies to Russia led to the fact that the famine in the southern provinces lasted throughout 1922 and the first half of 1923.

Translated by Jonathan Reilly

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook