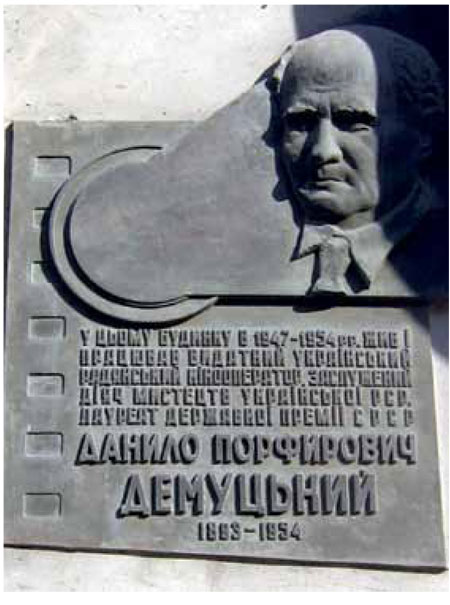

The Ukrainian Week continues to write about prominent people in Ukrainian history, who, as victims of the state-repressive communist system were forced to make serious life choices. This article looks at Danylo Demutskiy, a Ukrainian cinematographer, who, in spite of his achievements in the film industry, was convicted by the Stalin regime and forced to adapt to the aesthetic demands of the soviet government.

On the eve of the modern age, European civilization invented an entire system of tools, which at that time, were called philosophical instruments. They ranged from the microscope and telescope to the photography of the 19th century. During the nation-formation era, Kyiv became the Russian Empire’s capital of artistic photography and the centre for a huge number of talented photographers, from experts in daguerreotype to artists of the World War I period. There was a kind of aesthetic instinct, related to the observation of the world through “philosophical instruments.” In time, photography was followed by filmmaking, which subsequently resulted in the formation of the Kyiv school of cinematography, one of its representatives being Danylo Demutskiy.

PEOPLE THROUGH THE PRISM OF THE CINEMA

Danylo Demutskiy came to cinematography in a very individual and unusual manner; not only through photography which was the passion of his youth (he was a member of the Nadar Kyiv art union, named on behalf of the French photographer of the 19th century), but also through the world outlook perspective.

Danylo’s father, Porfyriy, was one of the representatives of the Ukrainian social movement, a noble and a doctor. He dedicated his life to collecting and studying Ukrainian folklore and organized a village chorus. But sooner or later it was necessary to actually see the people, not only via social-political paintings, Ukrainian landscapes or photographs, but also through cinematography.

Mr. Demutskiy was one of those artists for whom the art of cinematography was like a game, which did not require much effort. He worked with Oleksandr Dovzhenko on his first films, Vasya the Reformer and Love’s Berry, followed in 1929 by Arsenal, which contains several brilliant scenes. For instance, a train speeding along without a driver, carrying World War I soldiers, who have lost their direction in the world due to an excess of freedoms, ends with a crash. This scene and subsequent crash were recreated in Runaway Train, a 1985 Hollywood film by Japanese cinematographer and screenwriter Akira Kurosava and director Andron Konchalovskiy who had a high regard for Ukrainian poetic cinema.

Another of Arsenal’s scenes depicts the death of one of the insurgent workers and his horses, rushing home to the native village through the winter steppes of Ukraine. The horses, urged on by the shouting of the people, suddenly respond with the words: “We hear you, we hear you, masters!” I have never seen anything like this horse race in any other films.

The film also shows the people greeting the Tsentralna Rada (Central Council). One scene that stands out is when an officer of the Ukrainian People’s Republic decides not to kill a revolutionary worker after questioning, as this officer is educated and probably a Christian. Subsequently, the worker does not hesitate to kill his saviour. At that time, the events of the 1917s-1920s were viewed as a conflict and a tragedy of the Ukrainian and Russian revolutionary elements. Danylo Demutskiy was able to reflect this in his camera work.

POETIC EYE-GLASS

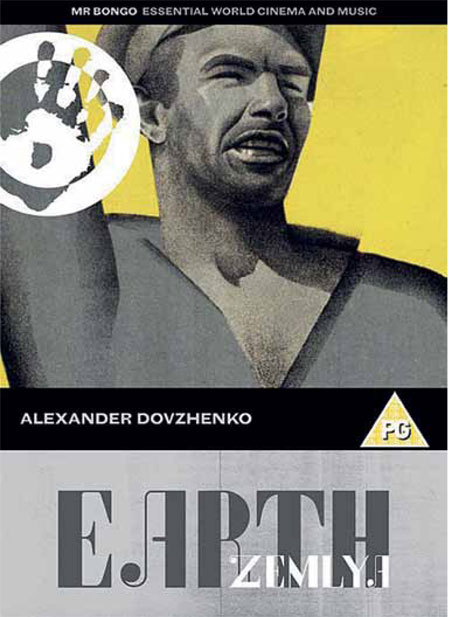

Demutskiy and Dovzhenko spent the summer of 1929 in the village of Yaresky, Poltava Oblast, filming Earth. It is difficult to say which of them could be considered the greater genius. Obviously the film-making process is usually dominated by the director, leaving the efforts of the camera man unnoticed. ButEarth features a unique harmony between the great director and the great cameraman. For instance, the famous episode showing the desperate, naked heroine rushing all over the house in her tragic beauty was not only the result of Dovzhenko’s efforts, but also those of Demutskiy.

In addition, Danylo invented an ad hoc ocular technology for his philosophical instrument, the camera, due to which, everything that appears on the screen seems to have come from a poetic dream, like some kind of internal language. Demutskiy’s incredible exposition is a unique phenomenon in world cinema.

These works impressed the cinematographic community of the world at that time and they are still impressive today. In Woody Allen’s Manhattan the main characters are having an impassioned argument. Suddenly, the viewers see the poster of the film which impressed them so much and caused the fight. It is Earth.

It was after this film that the drama began for Oleksandr Dovzhenko, drawing in his cameraman Demutskiy as well. Under the Sword of Damocles of Stalin’s terrors, they started to shoot a film entitled Ivan about soviet industrialization and the technological exploitation of the Dnipro River. In this film, the skillfully filmed industrial landscape is wonderfully integrated with the lyrical canvas of Ukraine’s central river. Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein considered this filming to be the best landscape camerawork he had ever seen in world cinema.

When Ivan was finished, in the spirit of the 1930s, a decision followed that the director and his cameraman had to be destroyed. Dovzhenko managed to escape from Ukraine to Moscow (a warrant for his arrest was already being prepared). But Demutskiy did not want to leave Ukraine, his native land, which was the source of his artistic life and creativity.

TORTURES AND FILMS

This was a personal catastrophe for Demytskiy. In 1932 he was arrested for the first time, based on fabricated slander. 1934 saw a second arrest, based on the same fabricated charges of anti-soviet activity. He was then exiled to Central Asia, namely Tashkent. In time, he was able to find a job at an Uzbek newsreel studio, but was arrested for the third time in 1937. He then suffered cruel, sadistic interrogations and almost two years of imprisonment – the terrible and tragic experience of a soviet prisoner.

After his incarceration, he returned to Ukraine a broken and devastated man. But then the war began and he was forced to go to Central Asia once more.

In Tashkent he worked as a cameraman for an evacuated cinematographer from Moscow and made a considerable contribution to the establishment of Uzbek cinema. The Adventures of Nasreddin is his best work of that time. It is a brilliant film, humorous and oriental, recounting the origins of the famous eastern character – a malicious parable about the absolute, supposedly ancient, rule of the local tyrants. This film became one of the most popular ones in soviet film distribution of that time.

Unfortunately, when Dovzhenko wrote a touching letter to Demutskiy, with an invitation to work together in Ukraine, nothing came of it. Danylo did not have another opportunity to shoot a single frame with the renowned Ukrainian director, though he hoped to do so, on his eventual return to Kyiv.

After the war Demutskiy was forced to shoot a propagandistic film entitled Secret Agent, directed by Boris Barnet, showing the heroism of soviet security officers, and a naval film entitled Days of Peace by Volodymyr Braun.

The Asian scenes from Taras Shevchenko, a film by Ihor Savchenko, was Demutskiy’s only significant work at that time. It was a wonderful representation of the beauty of the local landscapes against a background of the unbearable soldiers’ life. This film is the result of a deep understanding of Taras Shevchenko and of Demutskiy’s own terrible personal experience as a prisoner. In 1952 the cinematographer was awarded the Stalin Prize (first degree) for this film.

Danylo Demutskiy died at too early an age in 1954, several months into the Khrushchev Thaw. He did not witness the subsequent successes of the Ukrainian avant-garde cinematographer from Paradzhanov to the Ilyenko brothers. The latter worshipped Demutskiy, while Paradzhanov and Andriy Tarkovsky thought of him as a God-given cameraman.

There are very different interpretations of the films made at the Oleksandr Dovzhenko film studio. There can be criticism regarding the semantics of these films, many elements can seem to be a falsification and soviet pathos, but there was no bad camera work in Kyiv at that time. Cameramen remembered Demutskiy. His very presence in Ukrainian and world cinematography encouraged them to work as hard as they could.

BIO

Danylo Demutskiy was born in 1893 into a noble family in the village of Okhmativ, Cherkasy Oblast. He graduated from a Kyiv grammar school and later from the law department of the Saint Volodymyr University. He worked as a photographer and was an employee of the Vestnyk Fotohrafiyi (Photography Herald) and Solntse Rossiyi (The Sun of Russia) magazines. Later he cooperated with Les Kurbas’s Berezil theatre. In 1925 he received a golden medal for his photos at the International Exposition of Applied Art in Paris, started to work at the Odesa film studio as the manager of the photography workshop and shot his first films with Oleksandr Dovzhenko. In 1932 Demutkiy was arrested for the first time, then again in 1934 and deported to Tashkent, where he worked at the Uzbek newsreel studio. In 1937 he was arrested for the third time and imprisoned for 17 months. He returned to Kyiv in 1939. Demutskiy died in 1954 and was buried in the famous Baikove Cemetery in Kyiv.

FILMS

1926 – Vasia the Reformer; Fresh Wind; Love’s Berry

1927– Two Days; The Caprice of Catherine II; Forest Man

1929– Arsenal

1930 – Earth

1931– Fata Morgana

1932– Ivan; On the Great Way

1936– Kyrgyzstan

1937– Spring Country

1942– Blue Rocks

1943– The Young Years, Nasreddin in Bukhara

1945– Takhir and Zukhra

1946– The Adventures of Nasreddin

1947– Secret Agent

1950– Days of Peace

1951– Taras Shevchenko

1953– The Cranberry Grove