Members of the PNC officially transfer the command of General Haller’s Blue Army. Paris, 1917

The World War I dramatically changed the map of Europe, including the emergence of a Polish state, which had been carved among three empires at the end of the 18th century and now would be talked about by all sides in the conflict. The Austrian and German emperors issued separate proclamations in November 1916 with promises to restore Poland, the Russian tsar began his Christmas greeting for 1917 with the same promise, while even Woodrow Wilson mentioned the Poles from the other side of the Atlantic. As the war drew to a close, there was no doubt that Rzeczpostpolita II would appear. The main issue was simply where the borders of this new country should be, given that it had been one of the largest states in Europe prior to being dismembered.

The Polish question and Ukrainian details

The outline of the post-war world would be drawn up by the American president, Woodrow Wilson, who mentioned the establishment of “an independent Polish state…on the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations” in his famous 14 Points. The last was largely thanks to the Polish statesman and composer, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, who had effectively switched from piano to diplomacy in the United States.

Polish leaders found Wilson’s wording both encouraging and disheartening. In August 1918, Roman Dmowski, the leader of the right-wing National Democracy camp referred to as NDs in Polish, traveled to the US. There, he met with the president and afterwards sent a memorandum on the issue of the borders. Recognizing that only 25% of the population of Halychyna, then known as Galicia, was ethnic Polish, Dmowski declared that the Ukrainian people were not capable of self-organization and running a state as they lacked a sufficient intellectual class of their own.

“Thus in the near future, at least, a Polish administration is the only conceivable one for a normal development and progress,” he wrote to Wilson. “As long as the level of Ruthenian intellectual life is too low to produce a progressive modern government to be conducted by Ruthenians, Eastern Galicia should form an integral part of the Polish State.”

Ironically, Halychyna’s Ukrainians or Ruthenians as they were called in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, had been struggling with the Poles for half a century to establish their own national institutions. Ever since Halychyna had been granted autonomous status within the Habsburg Empire back in 1867, the government continued to be in Polish hands. Incidentally, Dmowski himself, among others, was a deputy in the Russian Duma and had signed a pact with officials from the Russian Empire in 1908 committing the Poles to suppress the development of the Ukrainian community in Halychyna.

During the war, Dmowski organized the Polish National Committee (PNC) and also influenced the formation of the POW and volunteer Blue Army, also known as Haller’s Army, under Gen. Joszef Haller in France. Where the PNC was oriented towards the Entente, Joszef Pilsudski, head of the Polish Socialist Party, was setting volunteer Polish Legions that fought on the side of the Quadruple Alliance. During the final year of WWI, the legionnaires refused to swear allegiance to the Kaiser. They were disbanded and Pilsudski was arrested.

RELATED ARTICLE: What shaped the aristocratic tradition in politics between the Cossack period and the liberation struggle of 1917-1920

On the last day of WWI, November 11, 1918, Pilsudski was released and returned in triumph to Poland. At this point, Poland’s political leadership was split between the PNC, which was operating in exile and was recognized by the Entente, and the temporary head of state, Pilsudski, who was actually running the country. Political expedience required some kind of compromise. The result was the formation of a coalition government led by Paderewski, while the PNC, now including Pilsudski’s people, became the official representative of the Polish Government at the Paris Peace Conference. And that was where the borders of postwar Europe were decided.

US President Wilson giving the Dove of Peace an olive branch labeled “League of Nations”. The 1919 caricature suggests that the Versailles system constructed by Wilson would not ensure a just order and long-term peace in the world

What shape Poland? Pilsudski vs Dmowski

The Polish National Committee was slated to discuss the eastern borders on March 2, 1919. Two different concepts were presented: Pilsudski’s and Dmowski’s and the winning concept became the basis for state policy and the Polish position during international talks.

Pilsudski floated the concept of a federation of Poland, Lithuania and Ukraine, an idealized notion that had echoed down the centuries from the early years of the Rzeczpostpolita, but it was not outlined seriously, looking more like a utopian idea. It was opposed by the NDs, whose own position was more difficult: the Polish state could be strong if its population consisted of more than 75% ethnic Poles. Dmowski’s argument was simple: “We cannot get caught up in the idea that the Sejm will have at least 75% Polish MPs, because, even if there are only 25% non-Poles, it seems obvious that it will always be possible to find 25% Poles who will have the ambition to cooperate with them…”

Dmowski supported his proposition with the example of Russia: “One feature of the Russian state was that its eyes were always bigger than its stomach. It swallowed a lot but it couldn’t digest it all. I know that we have appetites of our own, but we are clearly a western nation and should be able to control them.”

It was foolish to think that the NDs would limit themselves to only ethnic Polish lands. What’s more, the memorandum to Wilson openly talked about annexing Halychyna. Dmowski thought that this Ukrainian region, and part of Lithuania, needed to become those bits that Poland could and wanted to “digest” to the east.

RELATED ARTICLE: What national policy was like in the USSR

“Kresy Wschodnie [meaning eastern territories] are our colonies,” Count Zoltowski told the Committee. “They have always pretty much been so and they should remain so.” Not willing to go as far as annexing the territories, which could then become a problem, the Polish National Committee looked for those territories to the east that could be colonized with the least effort and polonized. They decided on Volynhia where, according to the 1897 census, 70% of the residents were ethnic Ukrainian and 6% were ethnic Polish. Even in the towns, the Poles were a smaller minority than Ukrainians, Jews or Russians.

“When it comes to Belarus, it’s hard to even talk about it as a nation,” said Pilsudski socialist Medard Downarowicz. “It hasn’t even crystallized. During the war, this territory was terribly depopulated, and Volynhia even more so. We could move our eastern borders in this direction. I think our expansion, our emigration, could very quickly penetrate to the east and these territories will very easily become Polish.”

“Pan [Downarowicz] himself said that we can move towards Volynhia,” concluded the meeting’s chair, Roman Dmowski.

Thus was the meeting of the Polish National Committee, where a vote of 10 to 4 against confirmed the territorial proposals and established the basis for Poland’s eastern policy. “Let’s remember that we cannot present to Congress the kinds of arguments that we have stated here,” the minutes of the PNC meeting read. “This territory is needed for us to expand, but we cannot say this at the Congress.”

So the issue was transferred to the walls of the Versailles, where the leaders of the victorious countries would decide.

The Versailles debates

In his memoirs, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George was to write years later: “Drunk with the new wine of liberty supplied to her by the Allies, she [Poland] fancied itself once more as the resistless mistress of Central Europe. Self-determination did not suit her ambitions. She coveted Galicia, the Ukraine, Lithuania, and parts of White Russia [Belarus]. A vote of the inhabitants would have emphatically repudiated her dominion.”

But not everyone agreed with him. Among those who favored the Poles was US President Woodrow Wilson. Although the Poles largely ignored the principle of self-determination of peoples, the Americans had their own interests in this case: there was a large and active Polish community in the US that represented substantial numbers of voters. The French were also keen, as they wanted to weaken Germany at all costs and this led to the formula that was then applied: “Several millions of Ukrainians, Lithuanians and Belarusians included in Poland means a corresponding strengthening of France’s eastern borders.”

Poland was represented at Versailles by Dmowski and Paderewski, and they were very successful in this. Their final argument for annexing the “Kresy Wschodnie” was the joint 600-year history of Poles cohabiting with such “primitive peoples as Lithuanians, Ruthenians and even Ukrainians [sic]” who supposedly not only did not lose their self-identity but, with Polish help, had developed it.

RELATED ARTICLE: The conservative revolution of Pavlo Skoropadsky: What the last hetman of Ukraine came to power in 1918 and what he achieved

But Poland resolved the issue of its borders not only on the diplomatic front but also in fact. “The Galician problem gave us no end of trouble. The trouble however did not come from Bolsheviks but from Polish aggression,” wrote Lloyd George. The struggle for the young Western Ukrainian National Republic (ZUNR) took place on many levels and one of them was getting the well-armed 100,000-strong Haller Army involved on the eastern front. This was against all the agreements and even France was forced to condemn the move harshly. But Pilsudski was a risky and overly experienced player who preferred a policy of fait accompli.

Memorial coin issued by the National Bank of Poland on the 100th anniversary of the Polish National Committee. Both sides include images of historical photos: members of the PNC in Paris and the oath of allegiance of the Haller Army. Both entities—the PNC on the international stage and the Blue Army with its weapons in Halychyna—are directly tied to the annexation of western Ukrainian lands by Poland

At this point, Paderewski would tell Versailles that they were unable to stop the whirlwind of 20-year-olds who were covering 35-40 kilometers a day without meeting any resistance. The local population was greeting them positively and all this campaign would cost the Poles less than 100 casualties.

“They [the Poles] are claiming three million and a half of Galicians,” said Lloyd George. “The only claim put forward is that in a readjustment you should not absorb into Poland populations which are not Polish and which do not wish to become Polish… The Poles had not the slightest hope of getting freedom, and they have only got their freedom because there are million and a half of Frenchmen dead, very nearly a million British, half a million Italians, and I forgot how many Americans.” He went on to call Poland a bigger imperialist than England, France or the US.

Paderewski then brought out the final argument to stop the debate: “On the day I left Warsaw a boy came to see me, a boy about 13 or 14 years old, with four fingers missing on this hand. He was in uniform, shot twice through the leg, once through the lungs, and with a deep wound in his skull. He was one of the defenders of Lemberg [Lviv]. Do you think that children of thirteen are fighting for annexation, for imperialists?”

RELATED ARTICLE: How Ukrainians treated different religions throughout their history

As someone once wrote about the heroic myth created by Henryk Sienkiewicz that had captivated Poles: “Heads and hands are being chopped off, mountains of corpses grow, but the blood is not real blood. It’s just beet juice.” This was understood in Versailles, so Lloyd George responded, “this charming artist beguiled the Council of Four.”

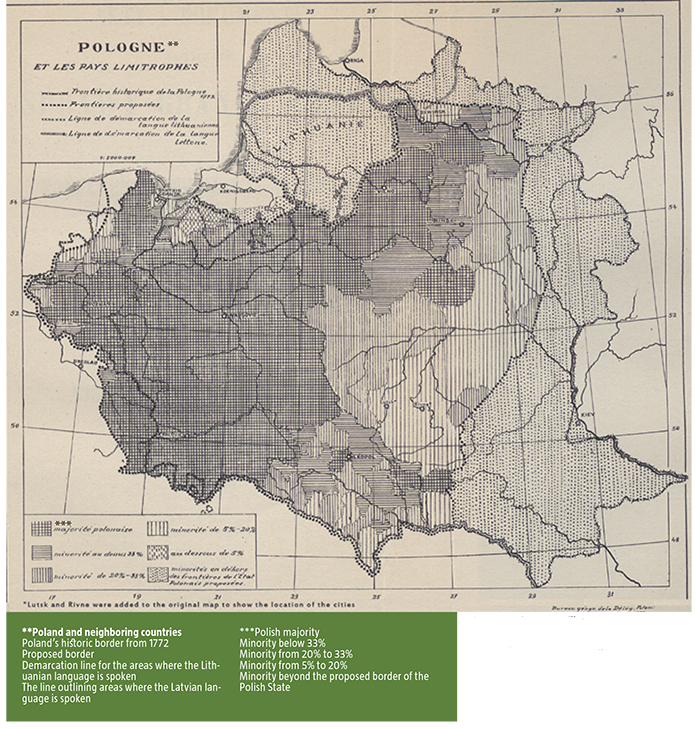

The new borders. The map approved by the Polish National Committee for the Paris Peace Conference on March 2, 1919, suggesting the outline for Poland’s frontiers

But the occupation of Halychyna proved to be a fait accompli and in June 1919 it was officially recognized in Paris. Poland was the first country to sign the Little Treaty of Versailles, in which it committed itself to respect the rights of ethnic minorities. The signatures were Dmowski and Paderewski.

By 1934, the second Polish republic unilaterally renounced the agreement on ethnic minorities. Nor was the promised autonomy of Halychyna established. When Lloyd George later listed the commitments unfulfilled by various signatories, this point took first place.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook