“We united Halychyna and Bukovyna with Dnipro Ukraine as dictated by the idea of the unified national Ukraine and the logic of history,” wrote Lonhyn Tsehelsky, the State Secretary and Minister of Foreign Affairs of the West Ukrainian People’s Republic in his memoirs on January 22, 1919. “Before the world, before history and our people that has just awoken to life as a state, and before the future generations, we have committed an act on which the future of our people should build.”

The Unification of Ukraine proclaimed in January 1919 was the working of history:Ukrainians had been supporting and developing the Ukrainian idea for a century before that, exporting it from one region to another.

Exported from the Left Bank

Modern Ukrainianness had a long path of evolution. This path stretched from East to West. The Left Bank Ukraine comprised of the Little Russian gubernia (former Hetmanate, i.e. Chernihiv and Poltava regions) and Sloboda Ukraine (Sumy and Kharkiv regions)was the harbourof the Ukrainian ideain the early 19th century. Unlike their peers in theRight-Bank Ukraine or Halychyna, the Left-Bankpolitical elite wasof the same national origin as the peasantry.

Therefore, it was no surprise thatIvan Kotliarevsky, a poet from Poltava region, usedthe local dialect asthe foundation for theliterary Ukrainian language, and that History of the Rus People, a book by an unknown author thought to be Bishop Konysky by its contemporaries, setthe foundation for the romantic myth of the Cossacks and the distinct origins of Ukrainians. Distributed as a manuscript, History of the Rus People was the intellectual phenomenon of its time. German traveller and geographer Johann Georg Kohl wrote about “entire districts in Little Russia where almost every household has a copy of Konysky’s History”.

The era of universities that began in the Russian Empire in the early 19th century spread to the Left-Bank Ukraine, too. The local aristocracy opened the university in Kharkiv to continue the Ukrainian intellectual tradition.

By contrast, the Right-Bank Ukraine, once it ended up under Russian control following the partition of Poland,was included inthe Vilnius education districtwith Polish Prince Adam Czartoryski as its patron. A lyceum opened in Kremenets, a town in Volyn, that later became knownas the Volhynian Athens. The town turned into a popular winter destination for the Polish aristocracy. “Manynoblefamilies moved from Paris to Kremenets for the Butter Week,” a Russian official wrote. In the end, theKremenets Lyceumhadas many students as ten gymnasiums in Moscow District.

According to theWorks of Ethnographic and Statistics Expedition to the West Ruthenian Land, the sole Ruthenian intelligentsia of the region was then comprised of the Orthodox clergy of Volyn and Podillia. They spoke Polish at home because such was the “requirement of decency”.

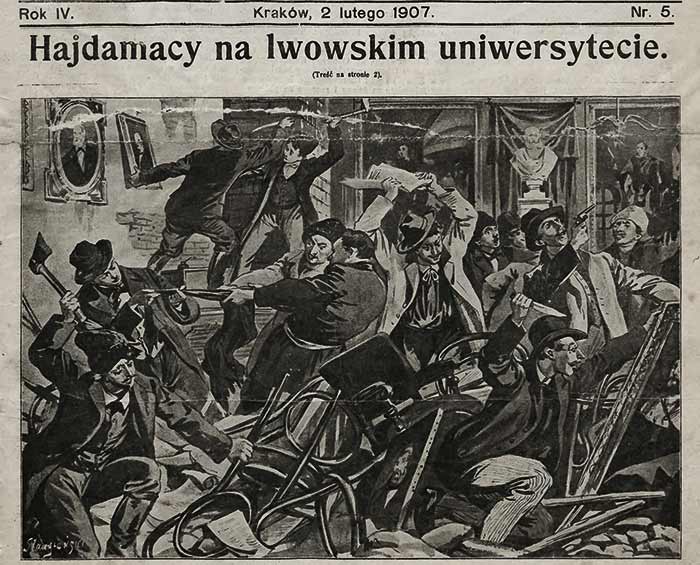

Haidamaky at the Lviv University was the title of the article published in Nowości Illustrowane, a Polish newspaper, on February2, 1907. Led by Pavlo Krat, originally from the Dnipro Ukraine, Ukrainian students took over the university premises and raised the blue and yellow flag over it

Meanwhile, Ukrainophile groups in the Right-Bank Ukraine emergedfrom the Polish community whereempathy forthe Cossacks gained popularityand the Ukrainian school emerged in the Polish literature.

The Western part of Ukraine was in no better shape underthe Habsburg Empire. Ukrainianness was representedthereby “priests and peasants”. Antin Anhelovych, the first Lviv Greek Catholic Metropolitan in 1808-1814, was said to “publish his brochures and addresses in French, German, Latin and Polish but not in Ruthenian”. In one popular account from the early 19thcentury, a peasant complained to the clergy about his priest’s refusal to fill inhis parenthood certificate. The priest justified his action by saying that he had studied Polish, German, Latin, Greek, Chaldean and Italian in schools and had certificates with good grades fromall of them, butRuthenian was not taught in the schools of Halychyna, so he really could not read a certificate written in Ruthenian.

RELATED ARTICLE: From the Law of Rus to Constitution

Soon enough, the first signal of national revival came when seminary students founded Ruska Triytsia, or The Three of Rus society. In fact, this title came from a mocking name the seminary students used for their only three peers who spoke Ruthenian, a people’s language.

While Sloboda Ukraine preserved the name Ukraine that later spread over its entire territory, the more nationally conscious young people in Halychyna were looking for the equivalents of a national name. They seriously considered the name Ruslans derived from the “tribe of the Roxolani”, a term borrowed from the Ukrainian School in thePolish literature.

Acrossthe Dnipro and the Zbruch

“Warsaw was dancing, Krakow was praying, Lviv was falling in love, Vilnius was hunting, and the Old Kyiv was playing cards. Itforgot before the revival of the university that it was destined by God and the people to be the capital of all Slavs,” wrote Michal Czajkowski, a representative of the Right-Bank nobility and the founder of Cossack units as emigre in the Ottoman Empire.

The emergence of Kyiv on the intellectual map was largely linked to the 1830-1831 Polish November Uprising. It was then that the St. Volodymyr University in Kyiv was established on the basis of the closed Kremenets Lyceum. This failed to solve the “Polish issue” for Russia, so the tsaristregime had to close the university or suspend studies there several times.

Regardless ofthe context, the Right-Bank Ukrainians felt separate fromboththe Poles and the Russians whose influences clashed on their lands. Kotliarevsky’s Aeneid and History of the Rus People played an important role in sharpeningthat feeling. “Shevchenko took entire episodes from History of the Rus People, and nothing apart from the Bible had morepower over Shevchenko’s system of ideas than History of the Rus People did,” wrote Ukrainian intellectual Mykhailo Drahomanov.

Arrests cut short a brief spark of Ukrainian political thought generated bythe Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius. Yet, the Ukrainian idea received unexpected support from one-time Polish nobility. Agroup of chlopomansfrom the Polish student corporation led by Volodymyr Antonovych and Tadeusz Rylsky fascinated with the culture of the peasants, chlopy in Polish, returned to theirnational roots and gave an impulse to the activity of the Kyiv Hromada community where they represented the Right-Bank group.

When the Russian Empire attackedUkrainianness throughthe Valuyev Ukaz and Ems Ukaz – “an intermission in the history of Ukrainophilia”in Drahomanov’s words — this served as an impetusto Ukrainian book publishing in Halychyna. For people from the DniproUkraine, this presenteda chance to publish their texts and help the Ukrainians under “the Habsburgs”.

Despite the successful upheaval of Ukrainian life in Halychyna during the 1848 Spring of Nations, subsequent developments were far from helpful to the Ukrainian cause. What happened to the founders of The Three of Rus society was illustrative: Ivan Vahylevych joined the Polish camp while Yakiv Holovatsky switched to the Moscowphiles. The latter posed a great threatastheir pro-Moscow sentiments infectedthe Greek Catholic clergy, the only Ukrainian equivalent of the upper classat that time. This was a desperate response to the de factotransferof Halychyna intoPolish administration in the 1860s.

Thesymbols of 1848 started getting a Russian gleam. The Halychyna Star newspaper switched to iazychie, an artificial mix of the local language and the Church Slavonic used by the moscowphile clergy. The People’s House, one of the most important cultural institutions, ended up in the hands of moscowphiles. Many leaders of the Ukrainian movement, including Ivan Hushalevych, the author of the first national anthem titled Peace on You, Brothers, became passionate moscowphiles. Soon enough, the term moscowphileswas replaced with saint-georgians after the Lviv St. George Cathedral, the main Greek Catholic church of the time. Society split into the hard and soft camps, the former supporting the official use of ethymological orthography used in the Russian language, and the latter opting for phonetic orthography that reflected the actual language spoken in that part of the country.

Children at the Ivan Franko School in Ustyluh, Volyn.1917. Ukrainian Sich Riflemen opened this school and 80 more during World War I

AsUkrainian literature from the DniproUkraine spilled across the Zbruch to Western Ukraine, it provided strong support to the embryonic Ukrainian forces opposing the moscowphiles. Some texts, including Kobzarby Taras Shevchenko were spread as manuscripts and learned by heart. More help came from both the right and the left banks of the Dnipro as the experience of organizing Hromadas, the national cultural groups of Ukrainian intelligentsia, was exported from Odesa to Halychyna. Hefty donations from Yelyzaveta Myloradovych and Vasyl Symyrenko, both descendants ofold Ukrainian families, helped found the Shevchenko Society and Prosvita, the civic movement focusing on cultural and national revival, in Lviv. Soon enough, representatives of the DniproUkraine joined these initiatives.

“People were coming from there, talented in elevated abstract debates, terrible freethinkers in theory, revolutionaries and atheists, barbarians in their manners. They did not acknowledge the manners of socialization accepted in Halychyna, brought axes with them, shouted loudly in public locales. Ladies came with short haircuts; they entered the apartments of gentlemen on their own, travelled to the distant Zurich for medicineunaccompanied, and did not care about their outfits or gloves; sometimes they did not even care about mere tidiness, boasting that they “loved going to pubs”. In a nutshell, they were people from adifferent world,” wrote poet Ivan Franko.

Still, he and his circle were seriously influenced by Mykhailo Drahomanov. Heinjected passion for political thought into the young generation in Halychyna.

RELATED ARTICLE: The strikes of opportunism and independence

Historian Mykhailo Hrushevsky, too,moved from Kyiv to Lviv thanks to his teacher Volodymyr Antonovych. Antonovych made arrangements with the Polish peers to have Hrushevsky as professor of Eastern European historyat the Lviv university. Hrushevsky helped rearrange the Taras Shevchenko Society into an academic one. It later functioned as the Academy of Sciences. Eventually, consensus between intellectuals from the DniproUkraine and the Polish elite of Halychyna ended the “alphabet wars”, making phonetic orthography official.

“Ukrainian Piemonte” and repayment of the debt

Researchers still debate about the author of Ukrainian Piemonte, a phrase used for Halychyna as a starting point for the liberation of Ukraine. Many believe that Volodymyr Antonovych coined it, but both Drahomanov and Hrushevsky used it in their works too. Between the 19th and the 20th century, Halychyna was the only Ukrainian region that could unite and launch the national revival.

This is not to say that people in Halychyna stood firm on their feet. They had only started calling themselves Ukrainians in the 1890s. Not too long ago,Panteleimon Kulish, a landmark Ukrainian writer, had emotionally referred to Halychyna as “garbage left after the Polish flood”. But Halychyna was undoubtedly starkly different from the part of Ukraine under Russia’s control. Yevhen Chykalenko, another Ukrainian intellectual, wrote the following report after his visit to Lviv: “I am now certain that Ukraine will not die indeed; unlike here, it’s not just Don Quixotes that fight for Ukraine in Halychyna– the streets do. Poles and Ukrainians compete even for the positions of gendarmes.”

Before World War I, the key actors of what would later become the Ukrainian People’s Republic were gainingexperience from life and work in Halychyna. Lviv shelteredMykhail Hrushevsky, Volodymyr Vynnychenko and Symon Petliura from the tsaristregimeand gave them work.

Before WWI, Halychyna residents were motivated to fight like no other part of the Ukrainian people. The first military formation known as the Ukrainian Riflemen actually emerged to “Liberate brothers Ukrainians from Moscow shackles.” Eventually, the greatest contribution of the Riflemen into the cause of Ukrainian unity wasthe opening of over 80 Ukrainian schools in the Russia-controlled Volyn, rather than in the battlefield.

Brothers Ukrainians eventually liberated themselves and declared the Ukrainian People’s Republic. ButHalychyna did contribute seriouslyto their struggle. Many soldiers of the Austrian army, especially the Ukrainian Riflemen on their way back from the Russian captivity in 1917, foundedthe Sich Riflemen, one of the most efficient segmentsof the Ukrainian People’s Republic Army. “Such army happens once in a thousand years,” Volodymyr Vynnychenko is rumored to have said about the Riflemen.

Unsurprisingly, when the Ukrainian People’s Republic delegation arrived for the Brest-Litovsk talks in January 1918, its first condition after the recognition of the UPR was “the unification of Kholm and Podliachia regions with Ukraine, and a referendum in Eastern Halychyna, Northern Bukovyna and Zakarpattia Ukraine”, according to the memoirs of the delegation leader Oleksandr Sevriuk.

The history of making the Unification Act official was not an easy one. It has to be signed, ratified and proclaimed four times between December 1, 1918, when the Pre-Introduction Treaty was signed in Fastiv, and January 23, 1919, when the Workers’ Congress in Kyiv approved the Unification Act. Even that was not enough. The final unification of the WestUkrainian People’s Republic and the Ukrainian People’s Republic was to take place after the Convention of MPs of both republics, which never materialized.

Reburial of Markian Shashkevych in Lviv. 1893. Halychyna had not gained its status of a “Ukrainian Piemonte” until the late 19th century

The first liberation struggle ended with the partition of the Ukrainian land between four countries. Apart from the bigger parts – the Ukrainian SSR in the Soviet Union and Halychyna and Volyn in the Second Polish Republic, Bukovyna and Zakarpattia ended up in Romania and Czech Republic respectively. Still, the developments preceding that partition did leave a trace on these territories.

“Ukrainians and Ukrainian (language and newspaper), and these names were embraced in the few months of war as widely as one would hope to in several decades,” wrote Bukovynanewspaper on May 7, 1915. Zakarpattia had a more difficult life. But the 1918 national upheaval revealed the aspiration of at least two centersthere, Khust and Yasinia, to join the Ukrainian land.

Ukrainianness had much less time for building its national self-awareness in this part of the country. Zakarpattia’s path was somewhat similar to what Halychyna had gone through earlier. Many migrants from the Ukrainian People’s Republic Army and the Ukrainian Halychyna Army went thereto teach, often competing with their former opponents, the Russian teachers and former officers of Denikin’s army, on the education arena. In 1920, Prosvita was founded in Zakarpattia, wielding as much influence on the local population as its predecessor had in Halychyna.

“The sun of Ukrainian statehood rosein the West” two decades later with the proclamation of Carpathian Ukraine in Zakarpattia in 1939. Great solidarity and support of Ukrainians from all over the world, including the most immediate neighbors in Halychyna and the emigres in Europe and America, hugely contributed to this.

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook