Leaving out the temporarily occupied territories, Ukraine has nine cities with a population of about a half-million or more. However, only five of them have become economic and demographic centers that are distinct, not just for their scale, but also for their heft at the inter-regional level and for their significant functions at the national level. These five include that capital, Kyiv, with 2.94 million residents as of mid 2018, and four smaller regional centers: Kharkiv with 1.47mn, Odesa with 1.01mn, Dnipro with 1.0mn, and Lviv with 0.76mn. Aside from Kyiv and Kharkiv, the other two ‘millionaire’ cities are somewhat unstable, as their population has been fluctuating around the million mark in recent years: It tends to fall with natural decline but people moving in from other cities compensate this decline in an unpredictable manner.

In terms of their role in the domestic economy and other aspects of the country’s life, these cities have been confidently distinguishing themselves from the country’s other major cities for years now. Cities like Zaporizhzhia with 740,000, Kryvyi Rih with 630,000, Mykolayiv with 480,000, and frontline Mariupol with 460,000, have only slightly smaller populations but often showed greater industrial output compared to Dnipro, Odesa and Lviv, yet they never achieved the inter-regional significance of any of the top five. Worse, they have been losing human resources and economic potential at an increasing pace in recent years, because of stagnation and the decline of their outdated soviet-era heavy industries.

By contrast, Ukraine’s top five biggest cities have been establishing themselves as multifaceted economic centers in their respective parts of the country, rather than as mere industrial or transport hubs. After a long period of declining populations, the Big Five have more recently begun to stabilize and, in some cases, renewed growth. They are also distinct from Zaporizhzhia, Kryvyi Rih and Mariupol also because of their extensive suburbs, more and more of which are already reaching the 100,000 mark for population. Moreover, these cities have considerable outlying buffer territories that ensure them fairly stable prospects for expanding as the process of urbanization picks up pace in Ukraine. Indeed, they already are close to and even surpass the size of many European capitals: Prague at 1.3mn, Sofia at 1.24mn, Belgrade at 1.17mn, Stockholm at 940,000, Zagreb at 800,000, Riga at 640,000, Vilnius at 550,000, and Bratislava at 430,000.

For now, even without counting exurban areas and residents who are not officially registered, the five largest centers in Ukraine encompass nearly every fifth resident of the country, not including the occupied territories. If the exburban areas are added, more than a third of the actually working labor force and nearly half of the domestic economy are centered there.

Postindustrial paradoxes

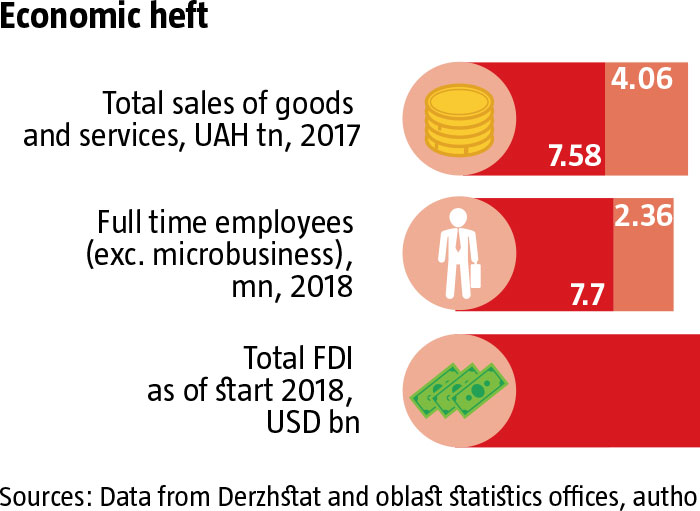

Unfortunately, Ukraine’s statistic agency does not provide data about the gross regional product of individual cities other than Kyiv, which is simultaneously considered a region and a city. In order to get a sense of the heft of the biggest cities as a whole and individually in relation to the domestic economy, the only way is to form an outline based on available figures for individual indicators. These include volume of sales for all goods and services by enterprises, industrial output, or the number of permanent employees.

The share of commercial sales of all goods and services in 2017 for these five cities was 54% of national sales, that is, UAH 4.06tn out of UAH 7.58tn. What’s more, not only Kyiv stood out against the rest, but also Dnipro, whose overall sales were almost twice as much as for Kharkiv and Odesa put together. On the other hand, some adjustment also has to be made in regard to what is meant by sales, including wholesale, for companies that are registered in their respective cities. For instance, 75% of the turnover in the Big Five is covered by Kyiv-based companies, whose volumes were double that of the nearest city.

In addition, the Big Five represent 31% of all permanent employees in Ukraine. This is significant because now payroll deductions now form the financial revenue base for local budgets. Permanent workers at large and medium enterprises are the foundation of the official labor market in Ukraine, providing not only payroll contributions to local budgets but also steady demand for goods and services, and personal loans ranging from consumer loans to mortgages. For this indicator, again, Kyiv and Dnipro stand out as permanent employees per 1,000 residents is considerably higher, not just than the national average, but also compared to Kharkiv, Odesa and Lviv.

RELATED ARTICLE: The Highest Heights of Lviv

Despite the enormous concentration of permanent employees in large and medium enterprises in the country’s biggest cities, these metropolises are also the main centers for small enterprises. For instance, 30.7% of all small businesses in Ukraine, that is, 99,000 out of 322,000 companies are based in Kyiv or Kharkiv. Unfortunately, other regional statistics agencies do not provide data on the development of small business in individual cities.

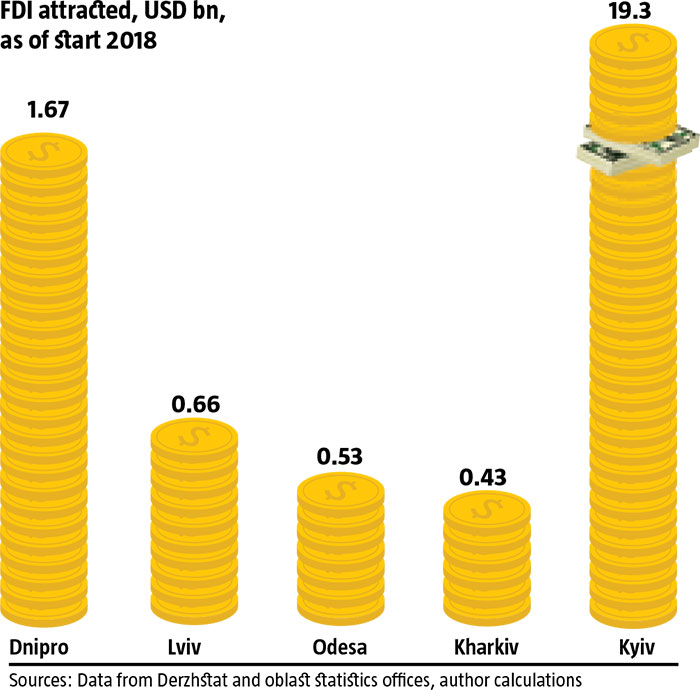

The biggest cities in the country are also the main portals for FDI inflows, although their individual roles in this process are extremely uneven. Altogether, nearly 57% of all FDI that has come to Ukraine since 1991 has gone to the Big Five. However, the gap between Kyiv, which has received close to half of all FDI or US $19.3bn out of US $39.9bn, and the other cities is enormous: the remaining four put together have only received US $3.3bn or about 16% of all FDI invested in Ukraine, less Kyiv. Among the remaining four, Dnipro has the clear lead, both in terms of total volume, at US $1.67bn, and in per capita FDI. Lviv is a distant second with US $656.3mn, Odesa comes third with US $530.9mn, and Kharkiv trails slightly with US $427.6mn.

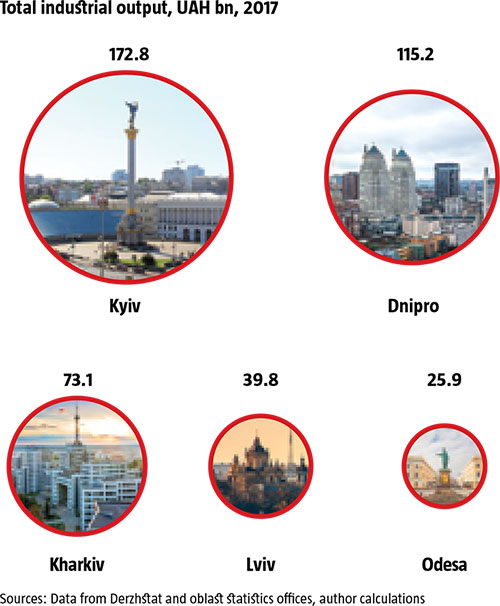

On the other hand, the Big Five represent only 20% of domestic industrial production, which pretty much matches their share of the population outside the occupied territories. Industrial capacities are typically located in completely different, smaller cities, even in these same regions and the role played by industry in the millionaire cities grows smaller every year, even in such traditional industrial regions like the Dnipro valley.

Today, for instance, Dnipro with UAH 115.2bn in industrial output trails far behind Kryvyi Rih, with UAH 159.5bn, and a slew of smaller industrial cities, such as Nikopol, Kamiansk and Pavlohrad. In Odesa Oblast, smallish Yuzhne produces almost half the industrial output of the oblast capital, despite being one tenth the size of Odesa. Kharkiv sold only UAH 72.8bn worth of industrial products in 2017, which was two thirds of what Dnipro sold, and barely half of what Kryvyi Rih sold, although the latter has less than half the population of Kharkiv. The biggest industrial county in Kharkiv Oblast is Balaklia County, which despite having a fraction of the population, manages to produce two thirds of what the city does.

Swapping stereotypes

Despite the stereotype, the leader in industrial output among the Big Five is the capital at UAH 172.8bn, which is half again as much as Dnipro, 2.4 times Kharkiv, 4.4 times Lviv, and nearly 7 times what Odesa produces. This simply testifies to the fact that even on a per capita basis, with the exception of Dnipro, Ukraine’s capital remains unequaled in terms of industrial development among the country’s biggest cities. Moreover, Kyiv’s industry has its own specific profile: its base is the food industry today, with 46.6% of all industrial output in the city and 17.9% of all food processed in Ukraine; then power generation and transmission, heating and gas supply, which add up to 20.1% of all industrial output in the capital and 8.4% of the domestic sector; and pharmaceuticals, which constitute 8.5% of industrial output in Kyiv but 50.9% of all pharmaceuticals being made in the country.

Modern-day Lviv, breaking stereotypes as well, is more industrial than Kharkiv or Odesa. Its output was worth UAH 39.2bn in 2017, beating Kharkiv, which is almost twice as big, on a per capita basis. Lviv also out-produced Odesa by a third, even in absolute terms, despite the fact that it has one third less population. More recently, Lviv has been actively attracting foreign investment to its manufacturing sector and its surroundings are seeing new factories being set up by major international companies, explaining how its total FDI now significantly surpasses that of Odesa and Kharkiv. And this despite the fact that Lviv’s population is significantly smaller. Moreover, its industrial component is likely to grow even more over time, while the conurbations of southern and eastern Ukraine see their industrial potential go into decline through a lack of initiative to reorient themselves towards cooperative links with western companies.

RELATED ARTICLE: Odesa: Through Cossacks, Khans and Russian Emperors

Compared to Odesa, Lviv also has a very dynamic tourist industry whose heft is also growing. The number of tourists visiting the city is close to 3mn today and they leave US $600-700mn behind every year, which brings over UAH 100mn to the municipal budget in the form of a head tax on tourists. At the same time, like both Odesa and Kharkiv, Lviv is one of Ukraine’s key gateways in terms of its connection with the outside world. Moreover, it’s the gateway to the European Union, with whom more than 40% of Ukraine’s foreign trade takes place.

Nevertheless, Kharkiv and Odesa continue to pay the bigger role as trade and transport hubs in relation to the rest of the world. Where the latter specializes in shipping by sea and has one of the country’s biggest wholesale markets, the Seventh Kilometer, Kharkiv plays a similar role in surface transport of freight. Statistics show that even greater volumes of goods are transported through Kharkiv than through Odesa and the city has its own mega wholesale market, the Barabashovo.

And yet, neither Kyiv nor Dnipro suffer in any way from being in the center of the country. On the contrary, this makes them the best locations for investments to be placed, it reduces their vulnerability to shifts in trade or transport and transit flows, and it allows them to focus more on serving Ukraine’s internal markets. Kyiv, as the capital, and Dnipro, as the center of the most powerful economic and industrial hub in the nation, will likely continue to strengthen their position in the domestic economy—even if the industrial component of their economies gradually shrinks.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook