On 31 October 1999, Leonid Kuchma, who had been the president of Ukraine since 1994, won a fiercely contested runoff presidential election and was preparing for his second term in office. “You will see a new president,” he promised to the people.

At the time, the country was drowning in a general crisis of non-payments. Businesses offset each other’s debts; the government preferred not to pay anything to anyone, including the long-suffering government employees; water cutoffs and power outages were common across the country. The newly elected president appointed Viktor Yushchenko, who was the head of the National Bank of Ukraine to the post of prime minister and tasked Yulia Tymoshenko with bringing order to the fuel and energy sector. In the spring of the next year, parliament was reformatted: the right-wing and centrists re-elected the leadership, replacing one that had been elected by the left-wing majority, and brought more parliamentary committees under their control.

By the end of 2000, mutual offsets of debts among companies took a nosedive. Real salary growth still lagged behind the annual inflation rate but the difference was as little as 0.9%, down from 9%. At the same time, the income of the population was growing faster than productivity, and this tendency would persist in the subsequent years. Against this backdrop, the so-called oligarchs, owners of privatized enterprises, resisted any transformations as much as they could, while the people grew increasingly discontent.

Following a “good” post-Soviet tradition, slow and partial reforms were carried out primarily in the interests of large capital. The government could not, and was unlikely to want, to force the richest to seek a social compromise and modernize production facilities, as was the case during the post-war reforms in Western European countries. Instead, it preferred to tighten the screws.

On 16 September 2000, Georgiy Gonganze, editor of the Ukrainska Pravda opposition online periodical, disappeared in Kyiv. In early November, a beheaded body was found in Kyiv which was identified as that of Mr. Gongadze. On 28 November, Socialist Party leader Oleksandr Moroz went public in the Verkhovna Rada with part of the recordings later dubbed “the Melnychenko tapes.”

On 15 December, the first tents set up by the participants of the 1989–91 “Revolution on Granite” rose at Independence Square. Precisely 10 years ago, on 9 March, the Ukraine Without Kuchma protest turned into mass turmoil in the streets of Kyiv.

Flowers and Fire

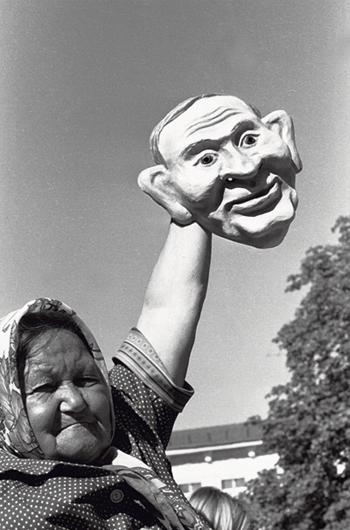

Taras Shevchenko’s birthday was the spark that kindled the fire. Reports circulated that President Kuchma planned to lay flowers at the Shevchenko Monument and this spurred both the political wing of the opposition (united into the National Salvation Forum) and civic activists involved in the Ukraine Without Kuchma movement to action. The government was perfectly aware of this and several thousand police cordoned off Shevchenko Park and the surrounding area.

The fight that erupted was formally triggered by a conflict between the police and Valentyna Semeniuk, head of the Kyiv branch of the Socialist Party. Citing MP immunity, she tried to get to the monument where the president was. She was hit on the head. The most aggressive of the protesters perceived this as a signal.Andrii Shkil, head of UNA-UNSO, and Socialist Party member Yurii Lutsenko, who were both present at the site, later flatly denied that any attack against the police had been planned in advance.

During the fracas the protesters broke a couple of times through the first several lines of the police. The present author remembers well the image of two sturdy UNA-UNSO members wielding a shield they had wrenched out of the hands of a special task force member. The protesters managed to get to the monument only after President Kuchma had left. Opposition MP Taras Chornovil set fire to the blue and yellow ribbon laid by the president. The police detained nine protesters, and one Berkut fighter was hospitalized.

Within two hours most protesters were already in front of the Interior Ministry building, which had been surrounded with a wooden fence allegedly “due to construction works.” The improvised fence was turned over, and eggs were thrown at the windows of the control post. The detained were soon released. Columns of demonstrators started off from Bohomoltsa Str. and from the ministry back to the city center. In particular, they went along Liuteranska Str., which is adjacent to Bankova Str. where the Presidential Administration is located.

The fence surrounding the Presidential Administration building today was nonexistent at the time. Instead, movable metal barriers stood on the corner with several lines of Berkut fighters in full gear behind them. The protesters’ attempt to get through to Bankova Str. could not but lead to a large-scale conflict. And it did. The police used their truncheons and their shields were repeatedly parted to let commandos charge into the protesters. In turn, the crowd began to ram the lines of defense with the mental barriers. Bottles and bricks flew into the air.

The breakthrough did not happen. Nearly 40 policeman were taken to hospital. At night, a true police roundup took place in the streets and at the train stations in Kyiv: any young person wearing national symbols was taken to be a protester. Only several dozen of the 1,500–2,000 demonstrators were directly involved in the skirmish, but over 200 people were detained and taken to police departments that night. Special task units literally demolished the office of UNA-UNSO without making any distinction in the process between “fighters” and male, or even female, journalists that were present at the site.

Later, 19 citizens were handed two- to five-year sentences for “organizing mass riots.” Interestingly, in early December 2010, the Prosecutor General’s Officereopened the case, but this is a different story altogether.

The Riots as a Dress Rehearsal

After the 9 March events, the Ukraine Without Kuchma movement dried up: part of the active protesters were disappointed with the organizational capabilities of the opposition, while the wide masses of people were simply shocked by the carefully dosed images of fights broadcast by the leading TV channels. Today, 10 years later, the entire truth about these events is still a question for historians to answer.

Radicals on both sides, of course, have their own version of the truth. To one side, it was and remains an attempt at a riot instigated, just like the Orange Revolution, by the hirelings of the almighty American forces. The other side believes the events were provoked by special security services. Representatives of this side differ only as to who exactly executed the provocation. Not surprisingly, the left accuse the ultra-right activists, while the latter pin the blame on police provocateurs who infiltrated the crowd.

Could the events have taken a different course a decade ago? There is no clear answer, because such riots resist external control regardless of plans drawn up by cabinet strategists.

The situation was no doubt controlled at the highest level — by President Kuchma. And he was in a dire situation. He faced powerful pressure from oligarchs inside the country, who were pressing for the resignation of Mr. Yushchenko’s “reformist” government, and the awakening of the active part of society. The situation was no better outside the country. On the one side was Russia whose new leader, Vladimir Putin, began a “land-collecting” operation, trying to bring under his control the countries through which Soviet oil and gas pipelines ran. On the other side was the West in whose eyes President Kuchma was afraid to emerge as another Lukashenko.

From the viewpoint of the government, the Ukraine Without Kuchma movement had to be crushed as soon as possible but without excessive severity in order to avoid international isolation and triggering a true revolution sooner or later. And initially it seemed that goal had been reached.

However, Kuchma did not avoid falling out of favor with the West in the long run: 2002 was marked by a scandal surrounding the sale of Ukrainian Kolchugasystems to Iraq. At the NATO summit in Prague, he was demonstratively seated away from the world leaders — to achieve that, the French, rather than the customary English, alphabet was used for seating. In 2004, social discontent which had been temporarily driven under the lid exploded in the vivid colors of the Maidan. In this sense, the Ukraine Without Kuchma movement indeed turned out to be, as its participants on all sides agreed, a rehearsal for the Orange Revolution, which was absolutely peaceful. The lessons of 9 March 2001 were learned by both sides, but the protesters did a better job of learning theirs.