A massive shift in the European natural gas market has been pushing prices down in the past few years. Ukraine sees this positive trend in the quotations on key European gas trading platforms and in the changing rates for commercial consumers at home. At first sight, this trend seems to be having a positive effect on Ukraine’s economy. But it hides serious challenges for Ukraine’s energy security and plans to expand domestic gas extraction.

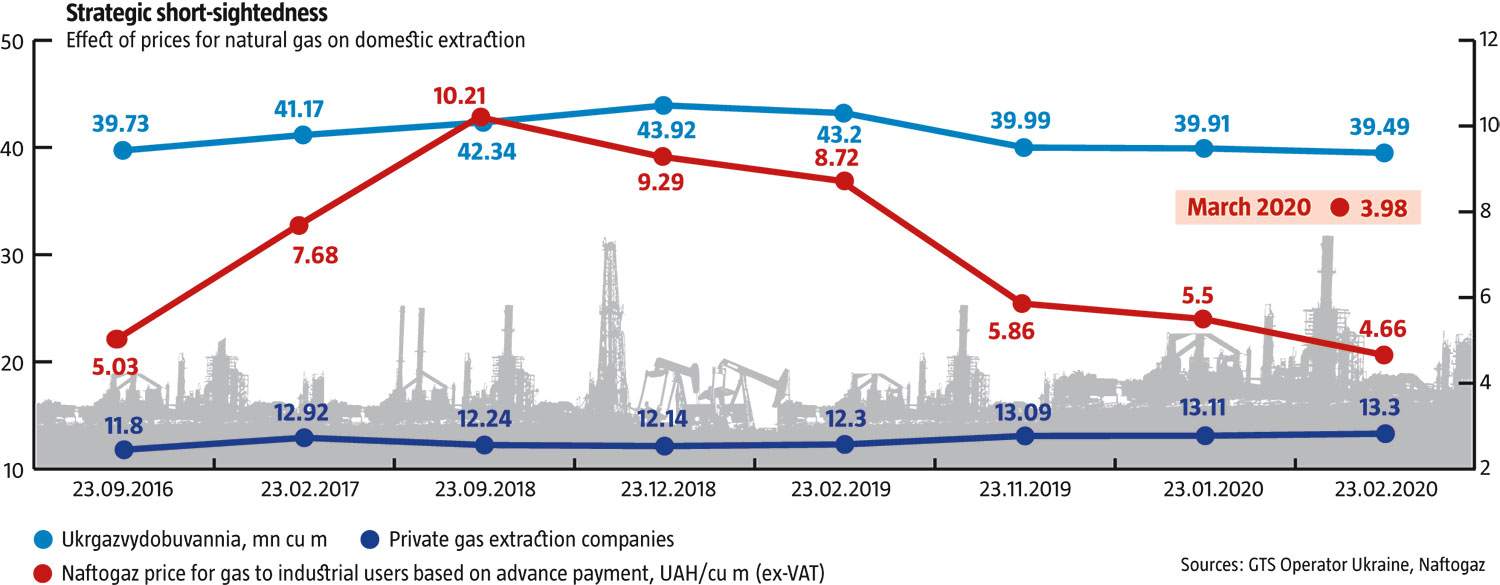

Unlike household users, commercial consumers in Ukraine have long been buying gas at prices shaped by the European market. At first, prices skyrocketed, going from a minimum of UAH 5/cu m ex-VAT in September 2016 to over UAH 10 in 2018. Then, prices started falling, going below UAH 6/cu m by the end of 2019 – and they are expected to go lower still, below UAH 4/cu m, in March 2020. At the current exchange rate, this is slightly above the traditionally subsidized price at which Russia sells gas to Belarus, US $127 at the border – although Aliaksandr Lukashenka reports that Russia is insisting on US $152 – and significantly below the US $173 at which Gazprom sells directly to Moldova.

In general, this nosedive on the global market stopped the growth of domestic household gas rates and even pushed them down a little. The price set for February was UAH 3.95/cu m ex-VAT plus transit or distribution costs, which is way below the UAH 4.27–4.28/cu m price in October or December 2018. But unlike commercial customers, Ukraine’s households barely noticed any change in rates, because the Government had, in 2017, kept household rates down at 50-65% of rates for commercial consumers relative to the 2016 heating season.

The 20% drop in gas rates for commercial consumers in just over a year was the result of a mix of circumstances: the EU and Ukrainian companies stocked up record-breaking volumes of gas in their storage facilities in anticipation of a gas war between Ukraine and Russia, and the winter was unprecedentedly warm. By early January 2020, stocks were still at 90 billion cu m, more than half the volume of gas that EU countries purchase from Russia yearly. A third factor was a longer-lasting trend of growing competition on the EU market between pipeline and liquefied gas as more LNG is produced around the world. Shipments of liquefied gas to the EU almost doubled in 2019, compared to 2018.

A honeytrap

These factors are likely to continue to make a difference for some time, but the trend could easily reverse down the line. Firstly, the weather could easily get colder and low consumption could gradually exhaust the record-breaking stocks. Secondly, times of plummeting prices and dumping tend to come with a redistribution of the market. Once this is completed, prices will go up again.

So where will Ukraine find itself after these balmy days of cheap gas? How much stronger or weaker will it be when the situation ends? Gas prices in the EU and Ukrainian markets have been going down in the past six years because of declining domestic extraction (see Strategic shortsightedness). According to Derzhstat, Ukraine’s statistics bureau, Ukraine extracted 10.04bn cu m or 3.4% more gas in H1’2019 than the 9.65bn cu m it extracted in H1’2018, but in H2’2019, extraction was down 13.6%, from 11.17bn cu m in 2018 to 9.65bn cu m.

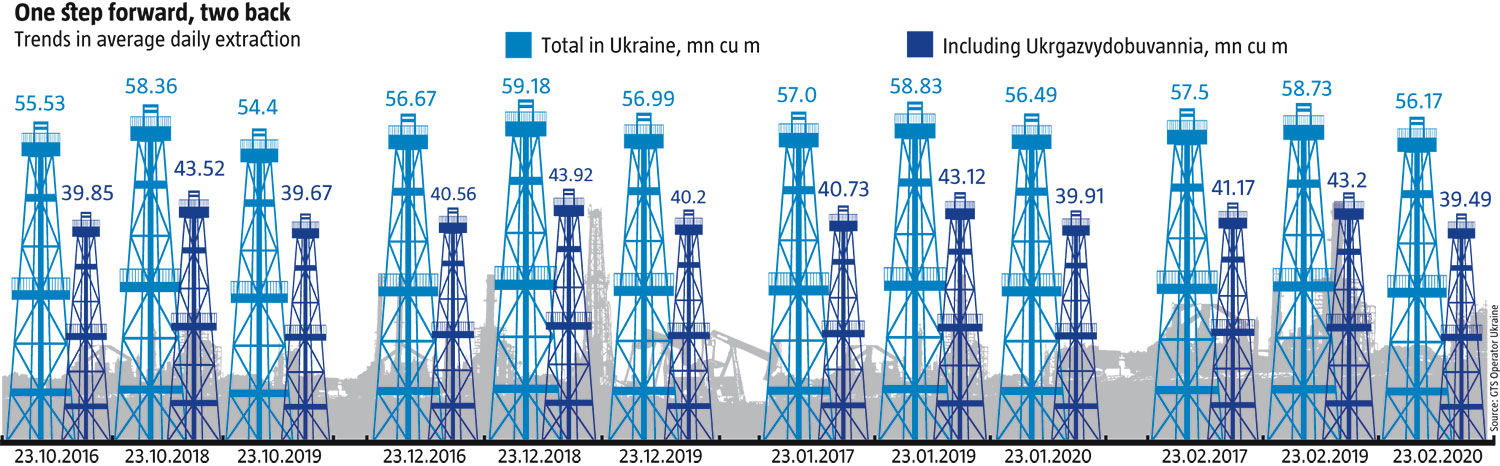

Naftogaz companies, including Ukrgazvydobuvannia, the extraction arm, and UkrNafta, were responsible for most of the decline. Ukrgazvydobuvannia produced 3.9bn cu m of gas in Q1’2019, an average of just 1.3bn cu m a month, and an even lower 3.6bn cu m or 1.2bn cu m monthly in the fall, for a gap of 10% between 1.33bn cu m in March and 1.19bn cu m in November. Where Ukrgazvydobuvannia was extracting 44mn cu m daily in December 2018, it was down more than 10%, to 39mn cu m recently (see One step forward, two back). This means 1.5-2bn cu m lost on an annual basis, by contrast to the increase of extraction, even if slow, in the previous years. Moreover, this is not the result of the depletion of gas fields.

As a result, in 2019, Ukrgazvydobuvannia’s extraction rate was back at 2015 levels, despite its plans to increase extraction to 20bn cu m by 2020 according to the 20/20 program announced in 2016. Meanwhile, private gas companies have continued to increase extraction, even if more slowly than in the past years, or maintaining levels, despite declining profits.

The worst thing is that top managers at Ukrgazvydobuvannia decided last year to prioritize current financial performance and profitability by sacrificing domestic extraction. Their rationale seems to be that as prices and profitability decline, extraction is no longer the priority. When Andriy Favorov, the newly-appointed head of the gas division at Naftogaz, presented the new strategy for Ukrgazvydobuvannia, he stated that the company’s priorities had shifted: “… we are no longer interested in cubic meters. We need to decrease the risks of drilling in new fields and increase the certainty of successful extraction. We will thus not increase extraction, but we will make the company more profitable.” Naftogaz’s Supervisory Board approved this strategy, which led to a steep decline in extraction, especially in H2’2019.

RELATED ARTICLE: Gas clinch

This has created a situation in which Ukraine will import more gas and make quick money on it. Gas imports by private traders grew almost as much in H2’2019 as domestic extraction dropped, compared to last year. ERU-Trading developed by Andriy Favorov before he joined Naftogaz was the biggest importer of gas until H1’2019, accounting for almost 25% of total imports by private companies.

Other major private importers included a number of Ukrainian companies allegedly linked to Dmytro Firtash and Ihor Kolomoisky through Azerbajiani Socar and the international Axpo group. But this started to change in H2’2019 when private companies began to import far more gas and EnergoTrade, a previously little-known second-rate player suddenly moved to the top. EnergoTrade nearly doubled imports compared to H1’2019, overtaking the two other biggest private importers.

Refocusing on gas imports instead of developing domestic extraction is the dangerous path of easy money for Ukraine’s energy sector. If this approach continues, Ukraine’s dependence on gas imports and the share of imported gas in overall consumption will grow. When the era of cheap gas ends, this will inevitably create new challenges for Ukraine as it becomes vulnerable to prices and sources of gas. These could lead to worse than just a likely rate hit for commercial consumers and households.

The rationale for shifting from domestic extraction to imports seriously threatens to revive the addiction to Gazprom gas, which is best placed to take over the Ukrainian market by dumping gas prices. What’s more, Naftogaz and the newly-established GTS Operator appear to already be preparing Ukrainians to accept the idea of direct purchases of gas from Gazprom through traders, claiming that there are no barriers to drawing up such a contract. Arranging to directly supply gas to certain Ukrainian consumers will provide the necessary instruments for the Kremlin to reach key political objectives in its hybrid war. By engaging top Ukrainian officials in these schemes and offering attractive discounts to industrial customers who are loyal to “Russkiy Mir,” the Russian world, the Kremlin will be able to count on their support in its ultimate aim of subordinating Ukraine.

Under the whip?

A wave of criticism for the failure of the 20/20 program and the decline in gas extraction in 2019 forced Naftogaz to quickly change the strategy that had been approved by the Supervisory Board just last year. On February 17, Andriy Favorov presented Trident, a new program whereby Ukrgazvydobuvannia would increase extraction. At its presentation, Naftogaz officials tried to explain why the previous 20/20 program failed and how the new one would deliver more volumes in just a few years.

The reasons for the failure offered by those in charge were mostly self-inflicted ones that could have been avoided or fixed with a bit of political will: “Red tape and politics blocked new licenses,” “Cheaper gas undermined the economies of extraction,” “25 years of poor investment in people and technology,” and “Energy consumption remains high.” The only objective ones included a simple claim that the biggest fields were depleted. All this might explain why 2018 output was lower than planned in the 20/20 program, but what it does not explain is why extraction mostly slipped in 2019-2020, especially after the company’s strategy changed in H2’2019.

In short, Naftogaz management offered nothing new. All they had to say was tired old rhetoric about how “Ukraine can no longer count on a steep rise in the extraction of hydrocarbons in the current fields with the available tools. We have come to the point where we need to launch a new project, about which there was only talk in the past.” Their conclusion? “If we get going today, we should have the first results in two-three years.”

The question is, why waste time on changing a strategy, prioritizing profitability over volumes? Naftogaz offered no explanation. The Trident program is based on extra-deep drilling, fracking and more proactive offshore exploration. The bet on shale gas extraction could prove problematic in Ukraine, given the opposition of environmental activists. A bet on offshore drilling could be equally risky, given how close it is to the Ukrainian platforms stolen by Russia in the Black Sea. It is also unclear what prevented Naftogaz from implementing an extra-deep drilling project all these years and successfully implementing the targets outlined back in 2016.

To avoid accountability for the failure of the 20/20 program, Naftogaz management has stated that both plans to increase extraction and plans to reduce consumption have failed. What is happening on Ukraine’s gas market deserves a closer look and a better response in state energy policy, including energy-saving policies. So far, the Government is doing nothing of the sort.

The data on consumption by various groups of users has shown no correlation whatsoever for years, and 2019 was no exception. For example, while household consumption went down more than 25% as a result of the warm winter, power companies used just 4% less gas in 2019, although natural gas is also used for heating purposes. And it is an important resource to reduce consumption of in a situation where most of the gas is used basically for heating purposes. Meanwhile, the volume of gas used to produce electricity soared, even though this type of power is far more expensive, while the generation of cheap electricity was limited during the year.

RELATED ARTICLE: Energy policy: stupidity or crime

For the government not to reinvest the lion’s share of profits from domestic gas extraction by Ukrgazvydobuvannia in expensive projects like extra-deep drilling to expand extraction is equally abnormal. Instead, the money is being pumped into the state budget through taxes and dividends. Over 2016-2018, UAH 40bn of investment was allocated to increase gas extraction, including just UAH 18.7bn for drilling. In 2019, Ukrgazvydobuvannia paid UAH 46bn in taxes ex-VAT, including UAH 13.6bn in dividends and UAH 23.5bn in rent.

Ukraine’s government gas policy should, first and foremost, offer solutions for the country to produce enough natural gas to meet domestic needs. A good balance of extraction and consumption is the only option for keeping gas rates for Ukrainian consumers, as that would allow Ukraine to replace the “EU hubs plus transit” formula with an “EU hubs minus transit” one. Most importantly, the domestic gas market would no longer be hostage to the Kremlin’s geopolitical games.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook