Photo: The poster at a rally says "Away with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union!"

According to a recent survey carried out by the Democratic Initiatives Foundation jointly with the Kyiv International Institute for Sociology on 12-21 September 2014, 3% of potential participants in the parliamentary election would vote for the Communist Party, which is 4.6% of those who have formed a clear electoral preference by now. Thus, the communists risk failing to cross the five-per cent threshold and not making it to parliament. To many, this is a definitive argument in favour of abandoning any active efforts to achieve a court ban on the Communist Party. Let them take away some votes from other pro-Russian projects; they won’t make it to the Verkhovna Rada anyway, these people seem to be thinking.

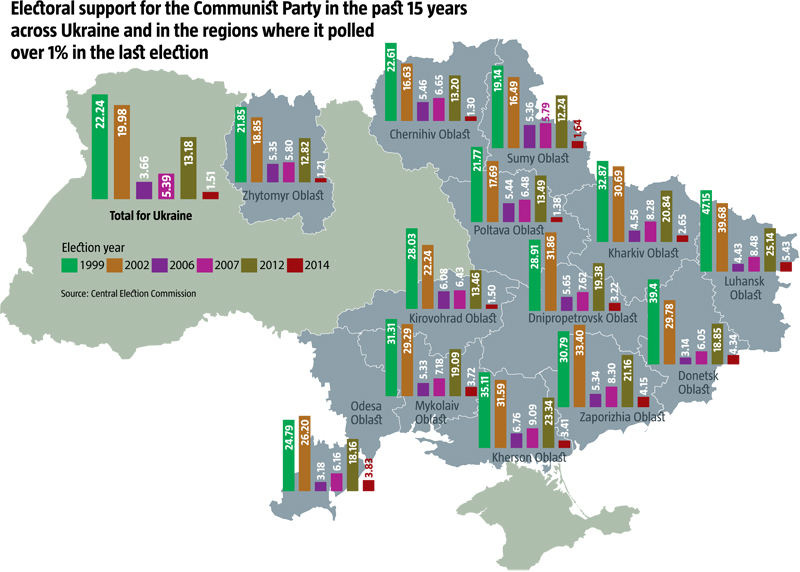

However, the Communist Party has gone through several such swings in the past 15 years – it was said to be close to demise but then rose as a phoenix from the ashes. In the late 1990s, it was the main apparent alternative to the Leonid Kuchma regime, until Nasha Ukraina (Our Ukraine), a national democratic alliance, came onto the stage to take the number one place from the communists in the 2002 parliamentary election. Their popular support dropped from 22% in the first round of the 1999 presidential election to less than four percent in the 2006 parliamentary election, the first one held after the Orange Revolution. The communist ship began to sink, it seemed, but it re-emerged with new strength, collecting over 5% in the 2007 parliamentary election and more than 13% in 2012.

RELATED ARTICLE: The Red Thaw in Eastern Europe

After the Revolution of Dignity (Maidan – Ed.), Petro Symonenko, the leader of Ukrainian communists, barely garnered 1.5 per cent. The communists did not receive many votes from their supporters who are traditionally concentrated in the Crimea and Sevastopol, now annexed by Russia, and in the Donbas territories currently controlled by terrorists. On 25 May, a mere 168,000 voters cast their ballots in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, which is a mere 5% of voter turnout in the past years. The communist nominee traditionally enjoyed the highest support level there in comparison to other regions, but this did little to improve his overall result. Moreover, there was another reason – by closely cooperating with the Viktor Yanukovych regime until the last minute and openly playing into the hands of Russian aggression after Yanukovych’s ouster, the Communist Party lost a good portion of its supporters in most regions of the country, ending up with virtually no followers in central and western Ukraine.

Heading into the last battle?

The party’s chances have risen somewhat now that a number of traditionally pro-communist industrial cities in the Donbas have been freed of terrorists. Moreover, southern and eastern Ukraine is becoming increasingly de-communized as evidenced by the recent demolition of what was Ukraine’s biggest Lenin monument (in Kharkiv). This may be an additional rallying factor for those consumed by nostalgia for Soviet times as it prompts them to vote for the communists, rather than the Opposition Bloc, on 26 October. Finally, the survey mentioned above shows that the communists have the most loyal support group of all the political forces elected to the Verkhovna Rada in 2012: 37% of communist sympathizers are going to vote for the Communist Party again, nearly 20% are still undecided and a little over 20% will not come to polling stations-. This means that the communists may actually obtain twice the number of votes that opinion surveys give them.

Their programme and rhetoric continue to include a typical array of social populist slogans, which, however, are highlighted to a much lesser degree than in previous campaigns: legal nationalization of strategic sectors; a ban on agricultural land sale; “abolition of the pension and medical reform imposed by the IMF and the EU”; repayment of savings; creating a network of state-owned and communal retailers, service providers and drugstores; providing free-of-charge housing to the underprivileged; limiting utilities to no more than 10% of family income, etc. Instead, priority is now given to slogans like “a secure shield against pro-NATO intentions”, “making a pathway for restoring good neighbourly and brotherly relations with the CIS members, above all Russia” and “preserving the unity of the Slavic peoples”. Moreover, “atheist communists” specifically emphasize their “support for traditional denominations” by which they, naturally, mean only one religious group – the Russian Orthodox Church, the religious hand of Russia’s FSB.

The Communist Party is heading into “the last battle” as a typical party appealing to the USSR-nostalgic pensioners. This is reflected in the composition of its list of nominees. Of the top 15 candidates, 10 are aged 61-76 and only three are under 50. The youngest candidate in the top five is the party’s leader Petro Symonenko, 62. Close to the top of the list are such odious fomenters of separatist attitudes as Alla Aleksandrovska (she recently said in Kharkiv that “Ukraine is not a state”), Spiridon Kilinkarov (a leader of Luhansk communists who has actively supported separatists), Yevhen Tsarkov (a Ukrainophobe from Odesa) and others.

Political nature abhors a vacuum

In the 23 years of Ukraine’s independence, political forces which aspired to left-wing status but, in fact, had no constructive social programmes and advocated a return to the Soviet past or preserving its rudiments in the social and economic spheres have been subject to gradual erosion. Ukraine has not been blessed with a normal centre-right political party all this while, but the situation in the left wing has been simply catastrophic. As the social structure of Ukrainian society evolved and nostalgia for Soviet times naturally abated, the communists and the socialists began to yield their spot in the political sun to social-populist political projects sponsored – often with little effort at disguise – by oligarchs.

To use Marxist criteria, modern Ukrainian society is largely “petty bourgeois” or “declassed”. Its social structure is conducive to social populism but not to classic left-wing ideology. In 2013, a lion’s share of voters depended on centralized distribution of the national product through the state budget, pension or other social funds rather than on money earned through employment by private capitalists. The majority of small entrepreneurs are barely making a living and would gladly take a well-paid job instead. 30% of the 10 million “self-employed” citizens are peasants who are, in fact, jobless and survive with the help of subsistence farming and irregular, seasonal employment as internal or external migrant workers. They are focused on surviving and take little interest in the traditional conflict over the distribution of added value between hired workers and employers – if only because this added value is simply not generated.

RELATED ARTICLE: The Right Model for the Right Europeans

Since the Orange Revolution, the traditional left-right electoral division has been increasingly supplanted by a civilizational choice between Russia as a continuation of the USSR and Europe. In these conditions, the choice first made by the communists and then by the socialists has alienated voters in western and central regions that lean towards social populism. In 2006, Natalia Vitrenko’s Progressive Social Party, once popular in central Ukraine, failed to be elected. Symonenko supported Yanukovych during the Orange Revolution, and socialist leader Oleksandr Moroz followed in his footsteps in 2006, which turned both left-wing political parties into junior partners of oligarchic capital in the pro-government coalition.

On 4 August 2007, speaking at a pre-election congress of the Party of Regions, attended by Ukraine’s biggest oligarch Rinat Akhmetov, Symonenko said: “Strange as it may sound, I urge all of us to protect national capital”. It would have made classic communist thinkers turn in their graves. As the Communist Party became more intimately involved with large capital, its programme was increasingly dominated by foreign-policy, rather than social and class, issues. This is no surprise, considering that it shared responsibility for the policies of the “anti-popular government” for more than five years within the span of less than eight years (2006-2014). Without its votes, the Yanukovych government of 2006-2007 and the Mykola Azarov government of 2010-2014 would not have been able to operate.

In these conditions, constituents in central, western and later southern Ukraine, where the existing social structure is more conducive to social populism, have not changed their preferences. The niche which belonged to the communists and the socialists was first occupied by the Yulia Tymoshenko Bloc (even though it tried to formally position itself as a centre-right force) and, after ensuing disillusionment, was penetrated by Svoboda (Freedom) and later Oleh Liashko’s Radical Party. This latter party started to gradually win over Svoboda’s voters. At least 9% of those who supported Svoboda in 2012 now prefer the Radical Party, according to the survey mentioned above.

RELATED ARTICLE: Bringing Eastern Ukraine Back Into the Fold

Closer inspection reveals that Svoboda’s socioeconomic programme and the rhetoric of its spokespersons are patently social-populist. Land to peasants and factories to workers – these familiar slogans are clearly discernible in its agenda. Svoboda insists that the local state administrations be dissolved and their authority transferred to the executive committees of the local councils. Further, it wants to ban strategic enterprises from privatization and restore state ownership of the already privatized ones, including cases when their owners have failed to meet their social and investment obligations. Svoboda is opposed to agricultural land becoming a commodity, wants to reduce the prices of basic goods by taxing luxury goods, legislatively limit interest rates on bank loans, etc.

Liashko’s party programme is even more populist: 10-year loans at a five-per cent interest rate, lower salary taxes and bigger taxes on products manufactured by oligarchs, a crisis tax on oligarchs to fill budget holes and stop the inflation, forcing oligarchs to shell out more for companies they privatized on the cheap, a ban on agricultural land sale and eliminating the illegal land market, a tenfold increase in budget spending on health, setting up primary health centres in every village, etc.

Thus, even as the old left-wing political parties are falling into oblivion, a new generation of politicians is coming on the scene. They are aptly exploiting the fact that a large proportion of Ukrainians lean towards primitive social populism, while still viewing the world through the Soviet lens despite embracing “nationalism” or adopting a “pro-European stance”. If continued, this trend will further erode assets that can still be redistributed to offer an easy solution to citizens’ problems at the expense of “that guy”. Moreover, this is happening precisely at the moment when the country badly needs the bitter truth and an ideology for generating the national wealth rather than dividing its dwindling assets. The positive aspect of the situation is that the programmes and rhetoric of Batkivshchyna (Fatherland), Narodny Front (People’s Front), Hromadianska Pozytsiia (Civic Position) and Samopomich (Self-Assistance) are, by and large, free of social populist elements