In this article for The Ukrainian Week, Viktor Kozyuk, Doctor of Economics and Head of the Department of Economics and Economic Theory at the West Ukrainian National University, along with Yaroslav Sydorovych from the European Cooperation Agency, delve into the complexities of international sanctions imposed on Russia, exploring their shortcomings and loopholes, and shedding light on how Russia has managed to gain access to billions of dollars despite the imposed restrictions.

As Russia’s full-scale invasion enters its third year, Ukraine is grappling with significant challenges. Its air defence resources are dwindling, Western weapons deliveries are delayed despite promises, and Russian forces are escalating attacks, shelling, and causing widespread destruction to civilian and energy infrastructure.

On April 12, 2024, the Council of the European Union approved a directive on minimum penalties for violating or circumventing EU sanctions in member states. This development is good news and demonstrates consistent support for Ukraine’s fight against the aggressor country.

The adoption of the draft law on criminal liability in the form of imprisonment and fines for violation of EU sanctions has been prepared and discussed since December 2022. After the legal act enters into force, member states will have another 12 months to incorporate the provisions of the directive into their national legislation. It is encouraging to see EU institutions adopting laws that bolster the effectiveness of sanctions. The next step will involve removing immunities from the reserves of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation, thereby depriving the terrorist state of ownership of these reserves as a form of financial punishment for its military aggression in Ukraine.

The bad news is that the sanctions imposed on Russia since February 2014 have not had a significant impact on its economy, failing to compel it to end the ongoing conflict and liberate the occupied territories of Ukraine.

On April 10, 2024, during the consideration of the Annual Report of the Central Bank of Russia for 2023, the Russian State Duma made a noteworthy observation: “The initial actions taken by Washington and Brussels to undermine our country targeted the financial system, particularly the banking sector. Despite these challenges, not only did our financial system survive, but it also emerged stronger than before.

In 2023, Russia’s GDP increased by 3.6% after a 2.1% decline in 2022. According to IMF data, the GDP growth in other countries was as follows: UK—0.6%, Italy—0.7%, Germany—0.9%, Japan – 1.0%, Australia – 1.2%, the Eurozone (20 countries) – 1.2%, France -1.3%, the EU (27 countries) – 1.5%, the US – 1.5%, and Canada – 1.6%.

The annual inflation rate stood at 7.4%. Meanwhile, Russia’s unemployment rate decreased from 3.9% to 3.2% over the year, marking a record low. The manufacturing sector experienced the strongest demand for workers, indicating potential significant growth in Russia’s military-industrial complex.

The Bank of Russia proudly announces that the issuance of replacement bonds and the conversion of depositary receipts facilitated the transfer of a substantial amount of frozen securities to Russia. The report succinctly states: “The volume of unblocked assets of Russian investors exceeds 3 trillion rubles.”

It is worth recalling the joint statement of the G7 leaders on December 6, 2023: ‘We reaffirm that consistent with our respective legal systems, Russia’s sovereign assets in our jurisdictions will remain immobilised until Russia compensates for the damage it caused to Ukraine. It is not acceptable for Russia to determine if or when it will address the damage it has caused in Ukraine.

How is it that the Russian central bank, which has been under sanctions imposed by Canada (February 28, 2022), the United States (March 1, 2022), the United Kingdom (March 1, 2022), Japan (March 1, 2022), Switzerland (March 1, 2022), the EU (March 2, 2022), Australia (March 3, 2022), and New Zealand (April 4, 2022), managed to unblock assets worth the equivalent of more than 33 billion US dollars, and the G7 countries did not prevent it?

Against the backdrop of a shortage of financial resources and arms supplies to Ukraine, the aggressor state is able to withdraw assets from Western sanctions equivalent to the value of 10 million 152-155 mm shells.

This is not the only troubling economic news. At a time when Ukraine is grappling with a shortage of resources in its fight against Russian aggression, the Ministry of Finance of the Russian Federation reported: “In December 2023, a portion of the National Wealth Fund’s funds held in accounts with the Bank of Russia, totalling 114,947.6 million Chinese yuan, 232,584.5 kilograms of gold, and 573.7 million euros, was sold for 2,900,000.0 million rubles. The proceeds were credited to the unified account of the federal budget to finance its deficit. Consequently, following these conversion operations, the account of the National Wealth Fund’s funds in euros with the Bank of Russia had a zero balance.

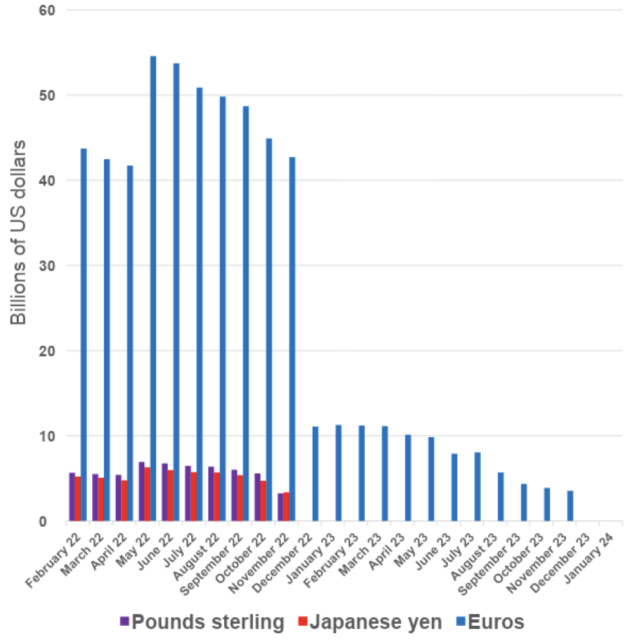

This marks the conclusion of the process to liquidate the Russian National Wealth Fund (RNWF) accounts, totalling 51.59 billion euros, 5.40 billion pounds sterling, and 809.81 billion Japanese yen, equivalent to 67.33 billion US dollars. It is deeply concerning that such substantial amounts of foreign currency assets did not simply vanish but were successfully transferred through correspondent accounts in reputable banks in Germany, France, Japan, and the UK. These funds were then utilised to procure machinery, devices, and electronic components from respected Western companies, ultimately contributing to the production of weapons used in Russia’s aggressive war against Ukraine.

Transformation and disappearance of foreign currency savings in the RNWF (in $ billion). Source: Authors’ infographic based on data from Russia’s Ministry of Finance

The “hellish sanctions” imposed on the Russian Ministry of Finance and its National Welfare Fund by Ukraine’s partners – USA (February 22, 2022), Canada (February 28, 2022), Australia (March 18, 2022), EU (February 25, 2023), Switzerland (March 2, 2023), Japan (May 26, 2023) – failed to prevent the disposal of these assets. The transactions involving a vast sum of funds held in the bank accounts of the sanctioned Central Bank of Russia could not have gone unnoticed by the banking systems of Brussels-Frankfurt, London, and Tokyo.

It is disheartening to acknowledge, but in total, the Central Bank of Russia and the RNWF have unfrozen foreign currency assets worth over $100 billion in equivalent (RNWF – $67.33 billion, Central Bank of Russia – $33 billion) over the past two years, thereby bolstering Russia’s military potential. Many observers of this situation may express frustration and offer lengthy explanations as to why this occurred and why it was challenging to prevent. However, what has happened cannot be changed, and it is crucial to focus on the future to prevent similar mistakes from occurring again. It is essential to heed the insights of experts who conduct thorough research and make informed decisions so that we can avoid the need for explanations in the future.

Experts in international law, economics, and finance from governmental and non-governmental organisations in many countries have been actively discussing the issue of confiscating Russian assets for some time. One of the outcomes of these discussions is a recent study available on the European Parliament’s website titled “Legal Options for Confiscating Russian State Assets to Support the Reconstruction of Ukraine.” This research serves as a reference for members and staff of the European Parliament to aid them in their parliamentary work. The paper thoroughly analyses the options for confiscating Russian state assets under international law to support the reconstruction efforts in Ukraine. The study focuses on the assets of the Russian central bank, of which $300 billion are frozen in various jurisdictions. It examines four methods to overcome Russia’s immunity from enforcement and assesses six proposals currently under consideration based on third-party countermeasures and collective self-defence. In general, the legal analysis covers four categories of property related to Russia, including Russian state property, assets of the Central Bank of Russia, Russian sovereign wealth funds and Russian oligarchs’ assets.

The document mentions the sanctioned National Welfare Fund (RNWF), managed by the Russian Ministry of Finance, and the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF), established as a political instrument at Putin’s initiative, are classified as “state-owned or controlled investment funds.” These funds are often financed by the sale of natural resources such as oil and serve various purposes, including “maximising returns with the same objectives, methods, and timeframes as private investment.” Unlike traditional central bank assets, the assets of these funds are not protected by relevant sovereign immunities. Therefore, it is crucial for Russians to unblock them.

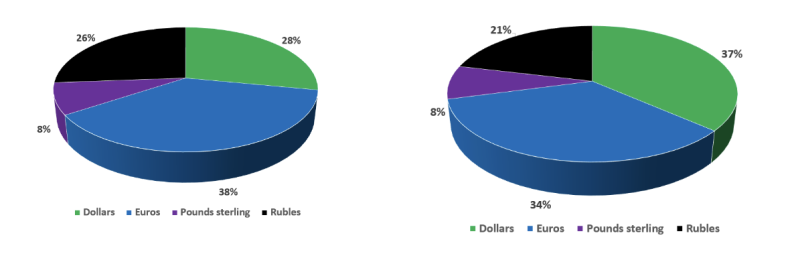

The RNWF was established in 2008 and is replenished with oil and gas revenues from the federal budget. An analysis of its structural transformations through the lens of historical events may suggest that decisions were made in the Kremlin long before these events occurred. US dollars, euros, and pounds sterling received from the export of oil products formed the basis for the regular replenishment of the RNWF. Even after Russia annexed Crimea and parts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions, and despite the sanctions imposed by Western countries, the accumulation process remained unchanged. In July 2019, there was a significant three-fold increase in currency inflows to the fund: from $15.33 billion to $45.53 billion, from €13.47 billion to €39.20 billion, and from £3.30 billion to £9.58 billion.

RNWF: February 2014 ($87,25 billion) and February 2020 ($123,14 billion). Source: authors’ infographic based on data from Russia’s Ministry of Finance

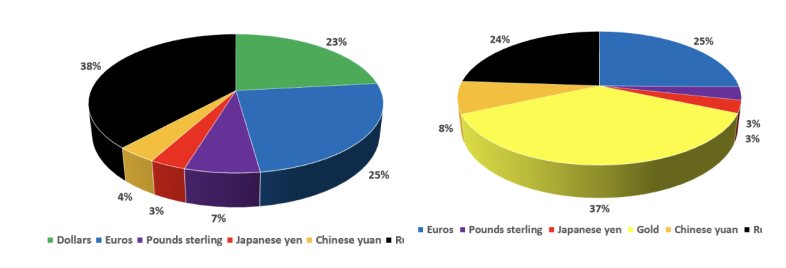

Since February 2021, the NWF has been replenished with the Japanese yen and the Chinese renminbi.

RNWF: February 2021 ($182,06 billion) and February 2022 ($154,82 billion). Source: authors’ infographic based on data from Russia’s Ministry of Finance

Certain political decisions in May 2021 can be inferred from the abrupt replacement of assets in US dollars with monetary gold and the resetting of the RNWF’s US dollar account to zero in July 2021. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the imposition of additional sanctions did not prevent the RNWF from receiving euros, pounds sterling, and Japanese yen, which continued until December 2022.

RNWF: February 2023 ($147,24 billion) and February 2024($133,53 billion). Source: authors’ infographic based on data from Russia’s Ministry of Finance

It should be understood that Russia’s RNWF continues to be replenished in accordance with the “budget rule” from oil and gas revenues, particularly from oil, gas, and gas condensate. However, the primary filling assets now include yuan, rubles, and gold, along with possibly the currencies of some “friendly” countries. Consequently, it is evident that Russia still possesses sufficient resources to finance the war against Ukraine and further develop the military-industrial complex.

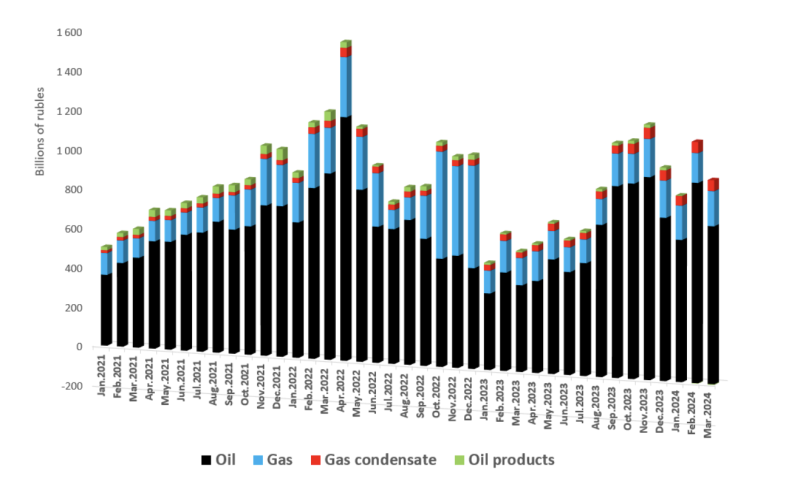

Dynamics of oil and gas revenues of Russia’s federal budget. Source: authors’ infographic based on data from Russia’s Ministry of Finance

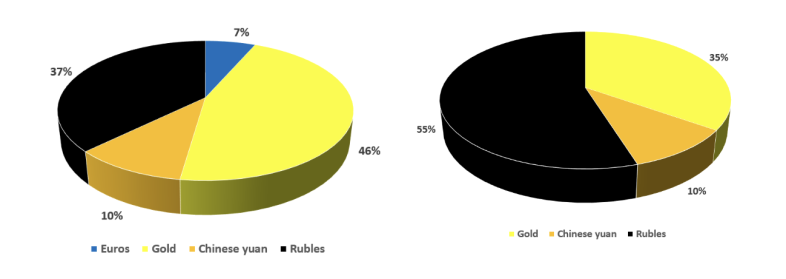

The dynamics of oil and gas revenues show a significant increase in the latter half of 2023, attributed to heightened oil sales and increased sales of gas condensate, which is not currently subject to sanctions. It’s worth noting that Russia, after eliminating assets in the RNWF denominated in US dollars, euros, pounds sterling, and yen, continues to use these currencies while gradually transitioning to others.

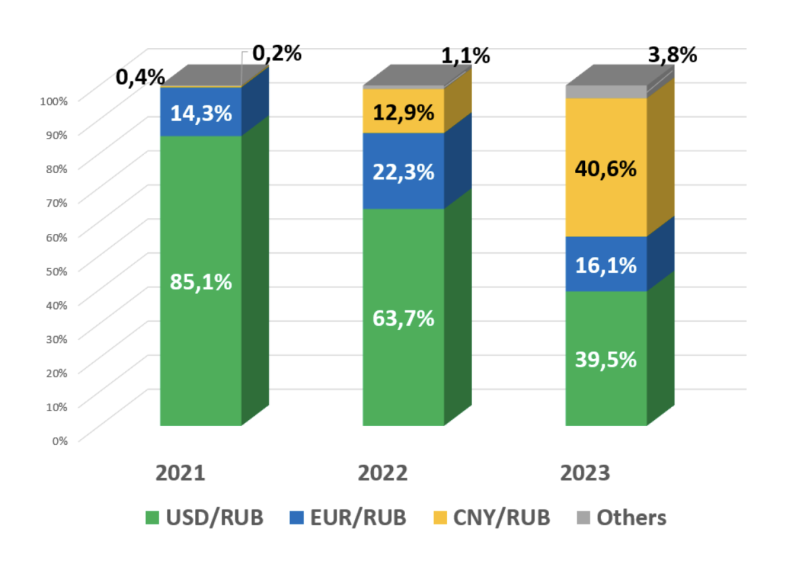

Share of currency pairs in Russia’s domestic foreign exchange market (%). Source: authors’ infographic based on data from Russia’s Ministry of Finance

In 2023, the US dollar accounted for 39.5% of the Russian domestic foreign exchange market, while the euro represented 16.1%. This raises reasonable questions regarding the nature of these transactions in light of sanctions restrictions and the impermissibility of creating asset withdrawal schemes to evade sanctions.

Currencies of the so-called “friendly” countries are actively traded on the Moscow Exchange spot market, including the Chinese yuan, Hong Kong dollar, Belarusian ruble, Turkish lira, Kazakh tenge, Armenian dram, Uzbek soum, Kyrgyz som, Tajik somoni, and South African rand. Additionally, the domestic foreign exchange market facilitates transactions in Indian rupees, UAE dirhams, and other currencies from a total of 32 “friendly” countries. Currently, Russian statistics employ criteria distinguishing between “friendly” and “unfriendly” countries, particularly in terms of the currencies used in export and import transactions.

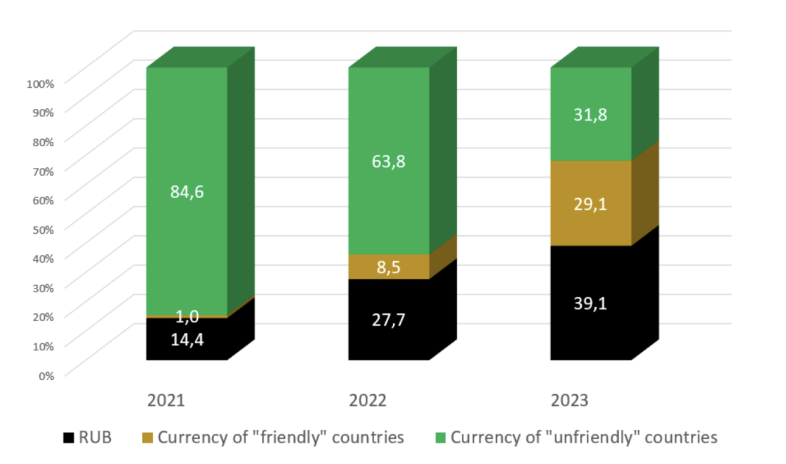

Currency structure of payments by the Russian Federation for exports of goods and services with all countries (in %). Source: authors’ infographic based on data from Russia’s Ministry of Finance.

Currency structure of payments by the Russian Federation for import of goods and services with all countries (in %). Source: authors’ infographic based on data from Russia’s Ministry of Finance.

Since 2022, the government of the Russian Federation has legalised the list of what it considers “unfriendly countries,” which is continuously updated. Hungary was added to the list in May 2023. As of April 2024, the list includes 49 states: Albania, Andorra, Australia, Bahamas, Canada, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Japan, Liechtenstein, Micronesia, Monaco, Montenegro, New Zealand, North Macedonia, Norway, San Marino, Singapore, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Korea, Switzerland, Taiwan, Ukraine, United Kingdom (including the British Overseas Territories (Anguilla, British Antarctic Territory, British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, British Indian Ocean Territory, Gibraltar, Cayman Islands, Falkland Islands, Montserrat, Pitcairn Islands, St. Helena, Ascension, Tristan da Cunha Islands, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, Akrotiri and Dhekelia, Turks and Caicos Islands) and the Crown Dependencies (Guernsey, Isle of Man, Jersey)), United States of America (including the U.S. Virgin Islands), European Union (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden, Czech Republic, Croatia, Denmark, Greece, Slovakia, Slovenia, Hungary).

It stands to reason that these states, akin to the Ramstein meetings where defence ministers of Ukraine’s partner countries convene to synchronise and expedite the provision of military aid to counter a full-scale Russian invasion, could establish a ‘Financial Ramstein’ format to address the issue of depriving Russia of financial and economic resources necessary to sustain the war.

The inefficacy of international economic sanctions against the Russian Federation, which has been in place since 2014, and the inadequacy of monitoring their compliance represent a significant challenge. Experts in international law, finance, and economics have long highlighted that mere asset-blocking sanctions are insufficient to deter Russia from its aggressive intentions. They advocate for the confiscation of sanctioned assets, including those of the reserves of the Central Bank of Russia.

Democratic countries adhere to the rule of law and act in accordance with laws and procedures. To date, only two countries in the world—Ukraine (May 21, 2022) and Canada (June 23, 2022)—have enacted laws allowing for the judicial confiscation of assets in civil proceedings of individuals and legal entities involved in facilitating Russian aggression against Ukraine. However, these laws currently do not permit the confiscation of assets protected by international agreements on sovereign immunity and mutual protection of investments. The bitter truth is that currently, no country in the world has a ready-made legal mechanism to confiscate Russian assets shielded by sovereign immunities.

This indicates that none of the countries that have frozen the assets of the Russian Central Bank reserves are prepared for the conclusion of the war in Ukraine and lack compelling arguments to compel Russia to compensate for the damage incurred. There is little hope for Russia’s voluntary agreement to pay compensation for all the losses, which, according to the third updated assessment of the World Bank, European Commission, and United Nations Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment (RDNA3), amount to USD 486 billion.

This figure does not include the damage inflicted by the aggressor country between February 19, 2014, and February 23, 2022, in the occupied territories of Crimea, Donetsk, and Luhansk regions. According to a comprehensive study by experts from the Kyiv Scientific Research Institute of Forensic Expertise, the damage caused to Ukraine as a result of Russia’s annexation of Crimea as of the end of January 2022 exceeded USD 106 billion.

To compel Russia to end the war, strong arguments should be presented in the form of laws adopted by Ukraine’s partner countries, creating legal mechanisms to overcome immunities and deprive Russia and its residents of their assets. The G7’s promise that “Russia’s sovereign assets in our jurisdictions will remain immobilised until Russia pays for the damage it caused to Ukraine” should be backed by a plan “B”: if Russia refuses to pay for the damage, the expropriation of all immobilised assets from the Russian Federation and its residents should be carried out and sent to the International Compensation Fund in The Hague.

In democratic countries, laws do not have retroactive effects, and adopting laws on the confiscation of Russian assets after the war ends may be too late and unfeasible.

The historic Summit of Heads of State and Government of the Council of Europe, held in Reykjavik in May 2023, established the Register of Damages Caused by the Aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine (RD4U), an important international legal framework with a high level of recognition of the proposed international mechanisms that will ensure fairness in compensation for war damage, increase trust between partners and reduce corruption risks. On April 2, 2024, at the 4th meeting of the Conference of the Register of Damage Participants within the framework of the Ministerial Conference “Restoring Justice for Ukraine” in The Hague, it was announced that applications for compensation for damages caused by Russian aggression were opened. Experts estimate that the Register will receive between 6 and 8 million applications from individuals, legal entities and government agencies.

However, the problem of filling the Compensation Fund, which should be carried out mainly at the expense of Russian assets, remains critical. We are confident that the 44 states that have created the Register of Losses will eagerly embrace the ‘Financial Ramstein’ format, including Australia, New Zealand, Taiwan, Singapore, the Republic of Korea, and other states intending to establish a new precedent for justice and financial accountability for state military aggression. The international Compensation Fund, currently under discussion, could be assigned broader tasks: compensating Western companies whose businesses have been suppressed by Russian authorities, managing the Fund’s assets for issuing securities, providing loans secured by these assets, and offering risk insurance, including transport logistics for goods and foreign investments, to aid in rebuilding and developing the Ukrainian economy.