Over the past few years, the role of state-owned oil and gas company Naftogaz in Ukrainian politics has changed dramatically. Until 2015, it was one of the biggest headaches for all governments, which regularly had to look for opportunities to cover the company's multibillion-dollar deficits. It has now turned into the most profitable state asset. Even though the prices at which the company sells gas to households and local heating companies are still far below market value, the narrowing of the gap between these numbers has allowed the monopolist to become highly profitable. In 2016, it had net profit of 26.5 billion hryvnias (~$920m) compared to 27.7 billion hryvnias in losses in 2015.

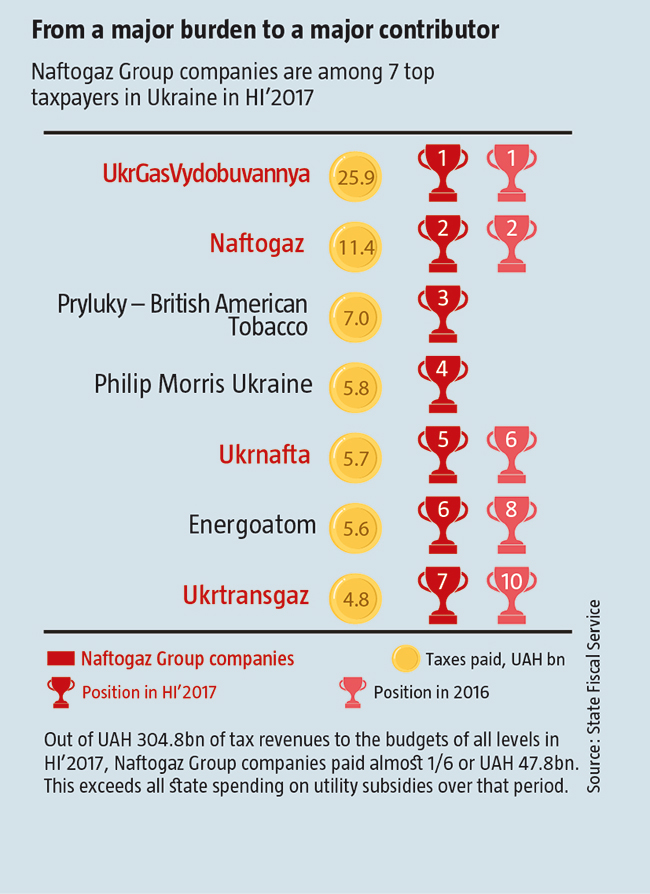

Naftogaz is now the largest company in the country, ranking first in terms of net profit and the amount of taxes paid to the state budget. Naftogaz Group includes four of the top seven taxpayers in Ukraine (see From a major burden to a major contributor). Put together, they provided almost one sixth of tax revenues for the consolidated budget in HI’2017 – 47.8 billion hryvnias. Based on these figures, as well as its number of employees, Naftogaz significantly exceeds the private empire of any Ukrainian oligarch in size.

At the same time, the success of Naftogaz and the prospect of managing multibillion-dollar cash flows and defining the future architecture of the highly profitable oil and gas market have predictably become one of the key themes for conflict in the conglomerate of power.

Who is in charge?

The improved financial position of Naftogaz and its subsidiaries is a consequence of reforms to the energy sector following the Maidan. The upscale of gas prices towards market levels, as well as reforms in corporate management that limited the government's ability to micromanage state-owned oil and gas assets have naturally led to greater commercial success for Naftogaz and its subsidiaries. For this very reason a five-member supervisory board was formed in spring 2016: one representative each from the Cabinet of Ministers (currently First Deputy Minister of Economic Development and Trade Yulia Kovaliv) and Presidential Administration (ex-Minister of Energy and the Coal Industry Volodymyr Demchyshyn), as well as three "independents" – Marcus Richards, Charles Proctor and Paul Warwick from the UK.

The improved financial position of Naftogaz and its subsidiaries is a consequence of reforms to the energy sector following the Maidan. The upscale of gas prices towards market levels, as well as reforms in corporate management that limited the government's ability to micromanage state-owned oil and gas assets have naturally led to greater commercial success for Naftogaz and its subsidiaries. For this very reason a five-member supervisory board was formed in spring 2016: one representative each from the Cabinet of Ministers (currently First Deputy Minister of Economic Development and Trade Yulia Kovaliv) and Presidential Administration (ex-Minister of Energy and the Coal Industry Volodymyr Demchyshyn), as well as three "independents" – Marcus Richards, Charles Proctor and Paul Warwick from the UK.

However, the formation of the supervisory board, completion of the first stage of reforms to the company's management system and increase of gas prices to market level coincided with the change of Prime Minister from People's Front Arseniy Yatsenyuk to Petro Poroshenko Bloc’s Volodymyr Hroisman. Andriy Kobolev, who was appointed as part of the People's Front quota, continued to lead Naftogaz. Ever since, however, the conflict between the government and the company has intensified.

At present, Naftogaz is a vertically integrated company that carries out the full range of field exploration and development operations, production and exploratory drilling, transportation and storage of oil and gas, as well as the supply of natural and liquefied gas to consumers. The management of Naftogaz insists that it should continue to operate as a vertically integrated company like the Polish PGNiG or Norwegian Statoil; it should incorporate at the very least gas production, storage and the sale of fuel to its end-users. Current Naftogaz chairman Andriy Kobolev argues that it will be easier for a large company to attract cheap credit resources abroad and therefore implement planned projects to increase the production of natural gas. In addition, the company's management sees it primarily as a large commercial player in state ownership, rather than a tool for solving the government's socio-political tasks.

However, the autonomous, vertically integrated company that the current leadership from the People's Front desires would prevent the Hroisman government from micromanaging the sector and restrict its freedom to use the company for achieving its political goals. An example of this is gas prices for the households and regional heating companies. Naftogaz insists on the full liberalisation of the gas market and the sale of fuel at market prices, rightly considering any subsidies to be a matter for the government and the state budget (to which it is the largest contributor). The company is well aware that separating the gas transmission operator from the rest of the group will reduce its EBIDTA by more than half, hoping to compensate for this by liberalising the gas market and keeping hold of its production arm.

However, the government, observing the growth of Naftogaz's profits, is seeking to reintroduce the practice of cross-subsidising for household customers. In other words, the gas price for certain categories of consumers is set artificially low due to the monopolist's resources that it receives from other activities and which with normal administration would, after taxes are paid, be reinvested or transferred to shareholders as dividends (in the case of Naftogaz, there is only one – the state). The policy of cross-subsidization led both Naftogaz and the gas sector of the country as a whole to the catastrophic state they found themselves in prior to the Maidan.

Immediately after his appointment, Hroisman promised that the rise in utility rates for the households at that time would be the last and the government has for two years blocked their indexation to match the prices on the European market. As a result, due to the devaluation of the hryvnia and rising gas prices in Europe, the fixed gas prices for household consumers in Ukraine are again lagging further and further behind market levels with each passing year. Consequently, continued keeping down of the prices artificially instead of annual indexation to match inflation over several years will inevitably provoke another sharp increase in the future. Just like in 2014-2016, when they had to be raised 6-10 times over.

RELATED ARTICLE: National champions wanted: How likely is it that companies with a global reach will emergy in Ukraine to become the drivers of an economic breakthrough?

For a long time, Naftogaz also opposed proposals to separate its gas transportation operations, despite the fact that the government passed a resolution to create a new company, Trunk Gas Pipelines of Ukraine. In recent years, potential problems that may arise for the Ukrainian side in Stockholm have been cited as the formal argument for blocking the division of Naftogaz and removing Ukrtransgaz, which is responsible for the transport of fuel across Ukrainian territory, from its control. An arbitration tribunal in Stockholm is considering Gazprom's and Naftogaz's complaints against each other regarding conditions for gas supply and transit. According to Cabinet of Ministers Resolution No. 496 dated July 1, 2016, the gas transmission operator should be separated no more than 30 days from when the final judgements take effect in the arbitration between Naftogaz and Gazprom. However, in mid-November, it became known that the tribunal had once again moved the deadline in the gas supply and transit cases to December 30, 2017 and February 28, 2018 respectively.

Despite the apparent disagreement over the approaches to further reform of the company, the conflict around Naftogaz is above all just one of the fronts in the war for key assets and levers of influence in the country that is being fought for by representatives of the various groupings that are in power. The issue is which faction will have authority over the largest state asset, which has recently been growing more and more profitable. Depending on the chosen scenario for breaking up Naftogaz in the course of its reform, the rivals of the People's Front have differing chances of gaining control over its constituent parts and related financial flows.

In July, Deputy Prime Minister Volodymyr Kistion, a close associate of Hroisman from his time in Vinnytsia who supervises the energy sector in the government, announced the preparation of a government decree On the approval of expected performance targets for the Supervisory Board of Naftogaz. The government did not have to wait long for a response – all three independent members of the supervisory board walked out in protest. Charles Proctor announced his resignation almost immediately (his powers were suspended in September), whereas Paul Warwick and Marcus Richards followed him a month later. Warwick directly pointed to government intervention in the activities of Naftogaz's subsidiaries as one of the reasons that influenced his decision.

After the supervisory board was incapacitated in this way, the government started to perform its functions, seemingly reaching its desired goal. However, tensions have since deepened between Ukraine and her Western partners, which have expressed concern that the situation could slow down the reform of the energy sector and pose risks for continued access to cheap credit resources from international banks. In September 2017, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) released an appeal to overcome delays in reforming Naftogaz and noted "with regret" that a situation had arisen in which the independent members of the supervisory board had no choice but to resign.

RELATED ARTICLE: Prime Minister Volodymyr Hroisman on challenges and plans in 2018

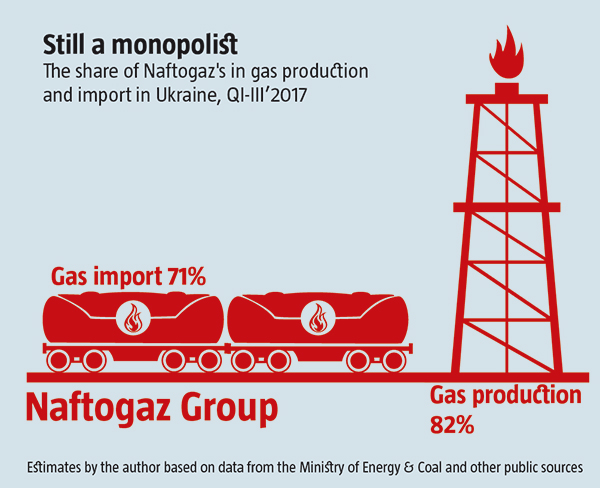

Meanwhile, Hroisman went further. On November 10, 2017, a government resolution abolished the competitive selection process for candidates to be independent members on the Naftogaz supervisory board. It also obliged the Ministry of Economic Development, to which Naftogaz is subordinate, to submit proposals to the Cabinet of Ministers with candidates for the positions of both independent members and representatives of the state. The Antimonopoly Committee joined the “war” on the government's side – the authorities probably intend to use it to increase pressure on Naftogaz on the grounds that it is a monopolist. At the beginning of November, Naftogaz stated that the results of analysis conducted by the company using standard European methods (the SSNIP test) suggest that it no longer holds a monopoly position following the integration of the Ukrainian gas market into the European one. However, the Antimonopoly Committee has requested evidence of this and announced the launch of its own investigation of natural gas markets in order to understand the competitive environment. "The committee will take measures set out by law according to the results of this investigation," read a statement.

The fight for the end user

Representatives of Western structures are increasingly lamenting that reforms in the Ukrainian energy sector, although they have begun, have not yet led to the necessary market liberalisation or the creation of conditions for competition in the wholesale and retail trade of gas with access to both the commercial and domestic end user. Among other things, this holds back Western traders from fully entering the Ukrainian market and, most likely, gaining dominant positions there. After all, they currently have to sell fuel mainly through Naftogaz or companies belonging to local oligarchic groups.

The strong expansion of private traders in the segment of gas supply for industrial consumers that has been continuing in recent years shows the scale of private companies' interest in the Ukrainian market, provided it is fully liberalised. Indeed, in QIII’2017, the number of private companies importing the fuel to Ukraine reached 40. Their share in the import of gas to the country reached a third of the total volume. In addition, foreign companies such as ENGIE, SOCAR, Trafigura and Vitol began to store gas in Ukrainian facilities. The Polish PGNiG also showed an interest in similar cooperation.

The largest non-state-owned gas importers remain companies that publicly available sources link with the main oligarchic groups in Ukraine. For example, structures close to Rinat Akhmetov, ERU Trading and DTEK Trading, continue to hold first place. Over the first three quarters of 2017, ERU Trading imported more than 0.53 billion cubic metres of natural gas. DTEK Trading accounts for another 20 million. Not too far behind Akhmetov's structures are companies associated with the Firtash-Liovochkin group (Promenergoresurs, Metida, RGK Trading and, most likely, VTP Energy). All of them bought fuel from the Swiss-registered company Nafta-Gaz Trading. Almost a quarter of a billion cubic metres of natural gas were also imported over this time by companies associated with Mykola Martynenko, a People’s Front MP, and more than 100 million cubic meters more by those linked to Mykola Zlochevskyi, former Minister of Ecology and Natural Resources in the Yanukovych era.

Over the first three quarters of 2017, ERU Trading imported more than 0.53 billion cubic metres of natural gas. DTEK Trading accounts for another 20 million. Not too far behind Akhmetov's structures are companies associated with the Firtash-Liovochkin group (Promenergoresurs, Metida, RGK Trading and, most likely, VTP Energy). All of them bought fuel from the Swiss-registered company Nafta-Gaz Trading. Almost a quarter of a billion cubic metres of natural gas were also imported over this time by companies associated with Mykola Martynenko, a People’s Front MP, and more than 100 million cubic meters more by those linked to Mykola Zlochevskyi, former Minister of Ecology and Natural Resources in the Yanukovych era.

However, alongside companies controlled by the main oligarchic groups, subsidiary companies of well-known foreign enterprises – the transnational Trafigura and ArcelorMittal, the Azerbaijani SOCAR and the French ENGIE – are also leaders in gas imports to Ukraine by volume. Although most of them only began to import gas to Ukraine in 2017, they are already among the largest players on the market. Indeed, Trafigura Ukraine imported nearly a quarter of a billion cubic metres in the first three quarters of 2017, SOCAR Ukraine over 200 million cubic metres and ENGIE Energy Management Ukraine and ArcelorMittal Kryvyi Rih around 100 million cubic metres each. It is obvious that the interest of European and transnational traders in the complete liberalisation of the Ukrainian gas market, the completion of the Naftogaz reforms and the end of state price regulation is much more considerable than that of local oligarchic groups that are already able to sell fuel to connected or dependent consumers in Ukraine.

However, these volumes are many times smaller than the market with regulated rates that Naftogaz continues to control. Since the beginning of last year, it has bought gas for its consumers from over ten European suppliers, which, of course, would have preferred direct access to the market. However, this is hindered by the administered prices for the households and the monopolistic position of local gas supply and distribution companies, most of which are associated with the Firtash-Liovochkin group.

RELATED ARTICLE: How energy efficiency helps energy security and saves for the future: the case of Ukraine

At the same time, the only thing that could ensure a new lease of life for Naftogaz if Ukrtransgaz and especially UkrGasVydobuvannya are taken away from it is the transformation of the company into a full-fledged gas supply structure with the ability to reach its end consumers. This refers to the public and the small and medium-sized commercial structures that currently buy fuel from local supply companies. The latter, though formally separated from the gas distribution companies, are in fact controlled by the old monopolists on the retail gas market, mainly from the Firtash-Liovochkin group.

Naftogaz has indicated that existing gas supply companies take advantage of the preservation of regulated (lower than market rate) gas prices for the population and municipal consumers to prevent competitors from entering this segment, which is currently the largest on the Ukrainian gas market. Therefore, the key demand of its current management for the reform of the gas market remains the real demonopolisation of retail fuel sales and access to end users for both Naftogaz itself and alternative traders. After all, if the artificial monopoly of Firtash's companies is not removed, Naftogaz's room for manoeuvre (and incidentally that of any private foreign gas traders) will be reduced to the role of "intermediary between the intermediaries". Its position will weaken rapidly following reforms.

Despite the multifaceted motives behind the struggle for the future and probably the legacy of Naftogaz, it is important that Ukraine end up a winner and not a loser as a result of competition between various internal groups of influence and external lobbyists for market liberalisation. It is in the national interest to create a highly competitive market without room for artificial monopolies, where various suppliers compete for the right to sell fuel or provide services for its transportation and distribution to both households and commercial consumers. At the same time, national security issues cannot be ignored. Gazprom has long wanted to enter the Ukrainian retail gas market and take control of it. Reducing the role of Naftogaz in the process of liberalising gas trade could increase the share of private companies associated with pro-Russian oligarchic groups in Ukraine.

In addition, European companies could, under certain conditions, decide (or be forced) to sell their Ukrainian sales subsidiaries to entities linked with Gazprom. Therefore, in the process of further reforming the sector, it is important to provide safeguards to prevent the Russian monopolist or related local oligarchic groups from taking over the Ukrainian market.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook