The Ukrainian Week continues a series of articles about ancient peoples that once populated Ukrainian lands, leaving behind unique cultural heritage. Following articles about the Celts, the Goths, the Alans and the Saka, this instalment focuses on the Yotvingians, Baltic tribes that left their mark on Ukraine’s topography. Below, read why the Soviet special services made an attempt to artificially “revive” the Yotvingians in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The Yotvingians were a Baltic people that lived in what is now Volyn, Ukrainian and Belarusian Polissia, the Podlachia region of Belarus and Poland, and the Narew and Neman River basins. They were divided into three tribes and populated a territory known as Yotvingia or Sudovia (“terra sudorum” in the earliest Western sources). Their language was close to Latvian, Lithuanian and the now-extinct Old Prussian. Chroniclers describe Yotvingians as being quick as animals, fierce and extremely courageous. They spent most of their lives fighting wars or hunting. Yotvingian tribes were involved in the genesis of several nations in the region: Lithuanians, Latvians, Belarusians, Poles, and even Ukrainians.

THE INTRACTABLE BALTS

Back in the 10th century A.D., Yotvingians served in the armies of Kyivan princes. In 945, a Yatviag Hunarev travelled to Constantinople with other ambassadors of Kyivan Prince Ihor.

The Poles and Rus’ wanted to conquer their lands, and in 983 Prince Volodymyr attacked and subjugated them to Kyiv. Together with his warriors, he sacrificed many captives and captured cattle to pagan gods. In 1009, Bishop Bruno of Querfurt, a German missionary, tried to baptize the Yotvingians and convert them to Christianity at the request of Polish King Boleslaw the Brave and thus subjugate them to Poland, but he was killed. In 1038, Yaroslav the Wise was quite successful in fighting the Yotvingians who were a nuisance to trade connections along the Western Bug River. However, chronicles claim that he did not capture their towns, unwilling to sacrifice his men to fight their fortifications. Instead, he seized a large number of cattle and other booty in the countryside and returned home. As can be seen, living amid forests and marshes, the Yotvingians had fortified towns which the Rus’ armed forces were reluctant to take by assault. Yaroslav made two more raids in 1040 and 1044.

As the ancient Rus’ became increasingly fragmented, the Galician and Volhynian principalities picked up the baton in battling the Yotvingians. In 1112 and 1113, Volhynian Prince Yaroslav Sviatopolkovych made two successful raids against them, which are briefly mentioned in a chronicle. The Tale of Ihor’s Campaign, likely written in 1185 by Volodymyr, the son of a Galician prince, mentions Yotvingia as a land hostile to Rus’.

In 1196, Prince Roman Mstyslavovych also sent an expedition against the Yotvingians, who attacked the Podlachia region. While the Yotvingians hid away in Prussian forests and marches, the militant ruler of Galicia plundered their land. In response, the Lithuanians and Yotvingians ravaged Turiisk in Volhynia in 1205, and in 1227 Yotvingian forces advanced as far as Volodymyr but were eventually repelled. They also attacked regions around Pinsk and Brest in Belarus, Poland and the lands controlled by the Teutonic Order. In 1248, when the Yotvingians assaulted towns in the Chełmarea, Prince Vasylko set out from Volodymyr and forced them to retreat. Their leaders, Borut and Skomond, were killed. The latter was known also as a priest who foretold the future by watching birds fly. The Rus’ warriors put his head on a stake according to an ancient custom. In 1251, princes Vasylko and Danylo, as well as the Polish Prince Siemowit I of Masovia defeated the united Yotvingian-Prussian forces, and Prince Danylo of Galicia subjugated them completely in 1256. But the recalcitrant Balts continued to rebel on occasion.

MARTENS IN EXCHANGE FOR CROPS

Chronicles not only contain a record of military events and the names of Yotvingian leaders (known as Kunigas) – Nebr, Stegut Zebrovych, Nebiast, Komat, Steikynt, Myntel, Mudeiko, Pestylo, Shurpa, Shiutr, Mondunych, Ankad and Yundil – but also tell us about their everyday lives and needs. In 1279, the Yotvingians sent ambassadors to Volodymyr-Volynskyi asking to be saved from starvation. They asked for crops in exchange for which they were happy to offer wax, silver and the fur of squirrels, black martens and beavers. Volodymyr Vasylkovych sent boats loaded with crops down the Bug River.

The Yotvingians were perhaps the last people of the region to still hold on to their pagan faith. According to Polish chronicler Wincenty Kadlubek, they believed that death was not to be feared because the soul would reincarnate in a more noble living being. Some would reincarnate as newborn children, others as beasts.

Yotvingian chiefs were forced to accept Christianity after they were defeated. In the late 13th century, northern Yotvingia came under the control of the Teutonic Order. It was plundered and many locals moved to Lithuania. But after the defeat of the Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Grunwald in 1410 and the Treaty of Melno in 1422, Sudavia, the entire territory the Yotvingians possessed, was incorporated into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. They left a number of traces in Ukraine such as in place names: the village of Yatviahy in Lviv Oblast, Yatviahy and Yatviaz in Volyn and Yatvizh in Chernihiv Oblast. The name of Lake Pulmo in Volyn is also thought to have Yotvingian origin. Until recently, place names were nearly the only source of data about the language of this people, because all or almost all Yotvingians had converted to Christianity by the 17th century and were assimilated by the Lithuanians, Latvians, Belarusians, northern Ukrainians and Masovian Poles. One copy of a dictionary of the Yotvingian language survived, although the original was tragically lost.

PAGAN DIALECTS FROM NARVA

The history of the Yotvingian dictionary – purportedly lost – traces back to the summer of 1978 when Viacheslav Zinov, a young man from Brest who collected antiques, travelled the Białowieża Forest in search of items to add to his collection. When he inquired about antiques with an old man from a remote hamlet, the man showed him several items from his own home. One book, a compilation of prayers in Latin with a few handwritten pages added to it, caught Zinov’s eye, and he purchased it. Once home, he realized that the manuscript was older than the book itself and it was actually a dictionary – a list of words in Polish and an unknown language. A note at the beginning of the dictionary said “Pagan dialects from Narva”. Some letters in the manuscript had faded, so Viacheslav carefully copied them into a notebook to decipher the text. He translated Polish words easily, yet despite all of his efforts, he was unable to make sense of the strange unknown language.

Before long, Viacheslav was enlisted in the army. While he was away, his parents who disliked his hobby went through his things and destroyed the icons and religious books out of fear that their son might become religious himself. The Latin prayer book with the curious handwritten dictionary was also destroyed. All that remained were the fragments that Viacheslav had copied into his notebook before he left for the army. When his service was over, he continued to research his discovery. After finding out that the Białowieża Forest had once been inhabited by pagan tribes that spoke a language similar to Lithuanian, he contacted researchers at the University of Vilnius. The notes shocked them: they now had a dictionary of the lost Yotvingian language that preserved it for future generations and revealed the culture and habits of this ancient people.

Yotvingian words from Zinov’s notes trace borrowings from Gothic, Alan and Slavic languages. Phrases found in the chronicles of Hieronymus Meletius that date back to the mid-16th century and allegedly stem from the Sudovians (a branch of Yotvingians often falsely attributed to Prussians) are also a blend of Baltic languages and Slavic elements. Baltic researchers are now using these fragments to recreate the Yotvingian-Sudovian language. Years prior, however, politicians attempted to create a Slavic Yotvingian language.

FEARLESS PEOPLE

“The Yotvingian people reside in the North, bordering with Mazovia, Rus and Lithuania; has a language greatly similar to the language of Prussians and Litvins, and understandable to them. The tribes are wild and warlike, so hungry for glory and renown that a dozen of them fought with a hundred enemies encouraged only by the hope and knowledge that, after their death, their compatriots would honour them with songs of their heroic deeds. This character led to the demise of the Yotvingians, as small groups were defeated by more numerous units and virtually all were killed because of their inability to flee from such unequal battles.”

-Polish chronicler Jan Dlugosz (1415-1480)

A YOTVINGIAN CHIEF FROM THE KGB

How the communist special services tried to drive a wedge between Ukrainians and Belarusians by reviving a separate Yotvingian people in Western Polissia

The rapid rise of Ukrainian and Belarusian national identity during perestroika in the 1980s and the growing interest of these two peoples in their native languages, history, ethnography and folklore made the KGB and the communist government nervous. Several political projects were launched to counter this trend. These were based on the constructionist idea that a nation is an “imagined society” created by intellectuals. The thinking was that it could be fragmented and new, loyal nations could be forged from it. One of the most vivid, exotic and, at the same time, abhorrent actions was the revival of the “Yotvingian people” and the “Yotvingian language” in the Ukrainian and Belarusian parts of Western Polissia.

A POLITICAL REINCARNATION

Mikola Sheliagovich, poet, journalist, teacher at the Minsk Police Academy and a KGB agent, was the leader of this political movement. In April 1988, he set up the Polisse Cultural Union which promoted “the revival of the Western Polissian language and culture” and the recognition of residents of Western Polissia as a distinct nation. He argued in the press that they were not Belarusians but, rather, descendants of the Balts, “Yotvingians”, and had their own “Yotvingian” language.

Since 1989, the Zbudinne (Awakening) newspaper was published as an organ of the Yotvingian revival movement. It was a biweekly publication written in a weird mixture of Ukrainian and Belarusian in which brand new coinages predominated. It should be said that Sheliagovich’s initial appeals attracted the interest of Ukrainian intellectuals in the Polissia region. They were ready to lend him a hand and act together. But once the Polisse Union was founded, it became clear that it sought separatism rather than the promotion of folk culture, so the Ukrainians severed contacts with Sheliagovich.

The political mission of the self-styled Yotvingians was completely pro-communist and pro-Russian. Their union received assistance from government ministers and Belarusian MPs, party functionaries, CEOs of government organizations, directors of leading factories and plants, newly rich businessmen and the almighty KGB. This handful of separatists were well-financed.

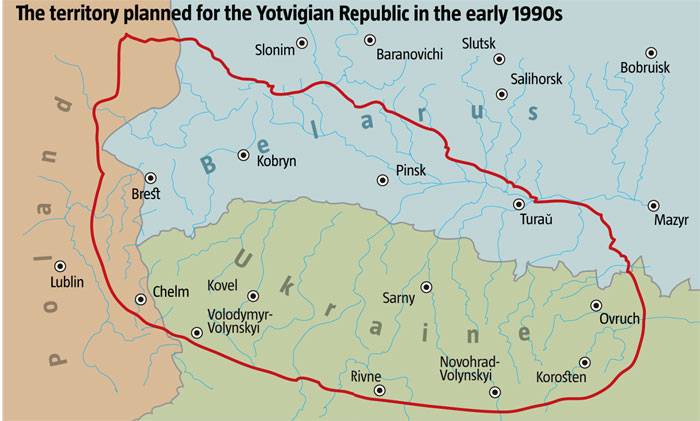

The chief of the “Yotvingians” made several claims: there was no Belarus; it could not have one language and culture; Belarus did not and would not have intellectuals or its own state; all things Belarusian were temporary, accidental and incomplete, while nationalists were the main enemy. His organization was effectively promoting the secession of Western Polissia from the republic. As a more radical option, Sheliagovich suggested forming a Belarusian-Polissian federation. There were even calls to set up checkpoints and a local national guard, but these remained on paper only. There were also territorial claims made against Ukraine.

In April 1990, a Western Polissia (Yotvingian) scholarly conference was held, declaring that the populations of the Brest and Pinsk regions of Belarus, the Volyn region of Ukraine, and the Podlachia and Chełm regions of Poland had the right to form an independent ethnic group. The conference was scheduled to take place in Pinsk, but the city turned out to be unprepared for the event, so it was moved to Minsk. Some presentations were made in “Yotvingian”. This gathering of separatists was made to appear more authoritative when it received welcoming addresses from Nikita Tolstoi, a leading Soviet Slavicist and specialist in the folk culture of Polissia, and his students Aleksandr Dulichenko from Tartu, Oleg Poliakov from Vilnius and Fyodar Klimchuk from Minsk. Five years later, Tolstoi participated in a congress of Ruthenian separatists in Slovakia where he welcomed the codification of the “Carpatho-Ruthenian literary language”. He was joined there by Dulichenko, another ardent advocate of the Ruthenians and the compiler of a two-volume dictionary of Russian obscenities.

FROM THE “YOTVINGIAN” LANGUAGE TO RUSSIFICATION

In contrast, some Belarusian public activists and authors such as Nil Gilevich and Zianon Pazniak, were very critical of Sheliagovich and his statements, correctly perceiving him as a KGB operative that threatened the territorial and national integrity of Belarus. Meanwhile, ethnographers proved that all Belarusians, rather than one particular group, had Baltic roots. The Polisse Union gradually fell into decline, failing to drum up the support of Polissia residents themselves, who found the artificial “Yotvingian” language foreign and barely comprehensible. Only one book – a chess handbook – was published in this language to date. Attempts to create a Movement of Western Polissia Residents, a Yotvingian National Party and a Western Polissian Regional Party all fell through.

In 1991-92, Sheliagovich still participated, with Tolstoi’s support, in congresses of Slavic cultures in Ljubljana as a representative of “Yotvingian culture”, while the odd Zbudinne newspaper, which experimented with the Latin script, was still available in newspaper kiosks in Brest Oblast and Minsk. Sheliagovich later distanced himself from the Yotvingian idea and became one of the most successful businessmen in Minsk. In 1994, he ran for president and later moved to Kaliningrad Oblast in the Russian Federation.

As soon as Alexander Lukashenko rose to power in Belarus and forced Belarusian-language and bilingual schools to teach in Russian, the “Yotvingians” mysteriously disappeared as if they had never existed. Not one supporter of their idea or speaker of the “West-Polissian literary language” remained. It seems they were all a mirage created by the KGB and the FSB in the first place. Lukashenko once defended the Polisse Union against nationalists at a meeting of the Belarusian Supreme Council, but he recently claimed credit for having prevented the division of the country and the creation of the Polissian Republic. The revival of the Yotvingians, aimed at dividing the Belarusian and Ukrainian nations, never came to pass.