Perched atop a 20-meter-high hill overlooking the 15-thousand-strong town lies the Ostroh Castle, dating back to the 14th century. This castle served as the ancestral seat of the princely family who derived their surname from the city’s name. Some 600 years ago, Ukrainian Prince Danylo Ostrogski laid the foundation of the castle, characterised by its singular donjon tower—a fortress where one could both reside and defend. The adage “my home is my fortress” undoubtedly rings true for the princes of Ostroh.

Exhibition halls of the Ostroh Castle.

In 1916, spurred by the local intelligentsia, a museum was established within the castle walls, initiating a collection effort that spanned the centuries. Over the museum’s tenure, more than 78,000 artefacts were amassed, offering insights into the life and culture of the region from 4 million years BC to the present day. Notably, the art collection showcases the evolution of Ukrainian art from the 10th century to modern times, featuring works ranging from icon painting to the masterpieces of Maria Pryimachenko and Mykola Hlushchenko.

Of particular intrigue is a collection of icons crafted by an anonymous artisan from Ostroh in the 18th century, renowned for his unique depiction of biblical figures—a style now immortalized as “smiling saints.” Equally captivating are the household items from medieval and early modern Ostroh, including the possessions of the Ostrogski princes, many of which survive as singular artefacts. The portrait gallery, situated in the castle’s grandest hall—a former reception room for esteemed guests—reveals the mysteries behind the portraits of the elite from bygone eras, offering a glimpse into the lives of those who once graced these historic halls.

Andriy Bryzhuk, Deputy Director for Research at Ostroh Castle, explores ten different artefacts currently housed in the castle’s museum, each symbolising the mysteries and glory of that era.

***

The icon of Prince Fedir Ostrogski.

The icon of Prince Fedir Ostrogski. The icon, painted on a copper plate, holds significant historical and religious importance. Prince Fedir Ostrogski, a renowned warrior and a “devout servant of God”, was chosen to lead the Volyn contingent of the army in the decisive Battle of Grunwald in 1410. This battle marked a turning point in the “Great War” between the Teutonic Order and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania on one side and the Kingdom of Poland on the other. Later in life, Fedir renounced secular pursuits and became a monk at the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra, taking the name Feodosiy. He resided in the remote Theodosius Cave until his death, where he remains buried to this day. In the late 16th to early 17th century, Prince Fedir was canonised.

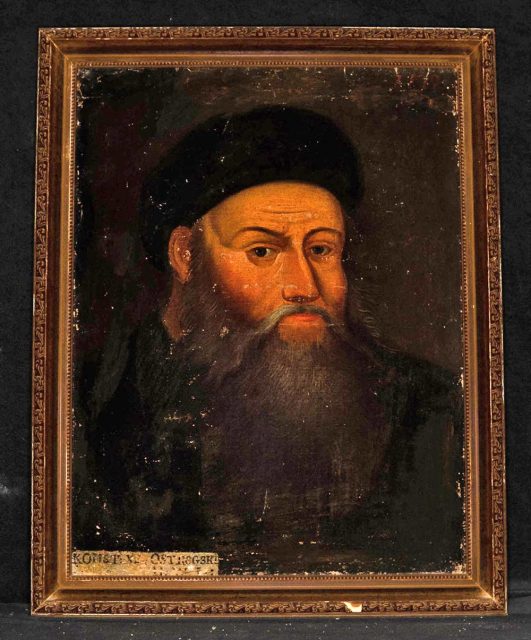

Portrait of Kostiantyn Ostrogski.

Portrait of Kostiantyn Ostrogski. He achieved remarkable success in military endeavours, winning an impressive 63 out of 65 battles. One of his most notable feats occurred in 1514, during the Battle of Orsha, where he famously defeated a significantly larger Muscovite army. Employing a tactic of feigned retreat, Ostrogski’s forces led the Muscovites into a trap, with cannons strategically positioned to inflict heavy losses. The Muscovite left flank was driven into a swamp and decisively defeated. In recognition of his significant achievements, Kostiantyn Ostrogski was granted the rare privilege of sealing documents with “red wax,” a right previously reserved for royalty. This privilege was subsequently passed down through generations of the Ostrogski family. On a portrait, Kostiantyn is depicted with a long grey beard, dressed in dark attire and a cap, and is inscribed with “Konst. xi Ostrogski 1529” at the bottom left; the portrait’s dating was long assumed based on this inscription. However, recent chemical analyses of the whitewash and paint suggest it was actually created at the end of the 18th century.

Portrait of Vasyl-Kostiantyn Ostrogski.

Portrait of Vasyl-Kostiantyn Ostrogski. He stood as the most illustrious figure of the Ostrogski lineage, earning the moniker “the old prince” and carving out a legacy unmatched by his peers. As the younger son of Prince Kostiantyn, esteemed for his vast wealth and influence as the starosta [senior royal administrative official – ed.] of Volodymyr, marshal of Volyn land, voivode of Kyiv, and senator of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, he transcended mere political and military realms to become a revered cultural patron. His ambitions extended beyond personal gain, dedicated to the advancement of Ukrainian lands. Under his stewardship, the city of Ostroh flourished, ascending to prominence as one of the foremost cultural hubs in Ukrainian territories. His affluence and authority were so formidable that posterity hailed him as the “uncrowned king of Ukraine-Rus.” In a revealing portrait, the prince dons a regal hat atop his oval face, adorned with a full beard, clad in a kuntush, a type of outer garment adorned with fur, buttons, and clasps. Clutching coins in his grasp, he gestures towards his wealth, a display reminiscent of modern-day rap videos where lavish spending is flaunted. Vasyl-Kostiantyn invited Ivan Fedorov, who printed his most famous books there, to Ostroh.

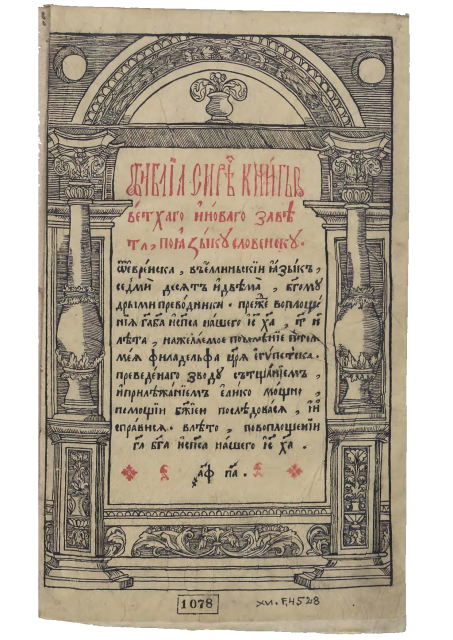

The famous Ostroh Bible.

The famous Ostroh Bible is among them. The Bible’s original copy is presented in the showcase. The Ostroh Bible is unique because it is the first complete Bible printed in Old Church Slavonic. In addition to the Holy Scripture, the book contains several poems, prefaces, and afterwords. In one of the poems, Vasyl-Kostiantyn’s accomplishments are compared to those of Volodymyr the Great, thus placing the owner of the Ostroh Castle in the history of Ukraine-Kyivan Rus’: “Volodymyr baptised his people, and Kostiantyn enlightened them with his wisdom of writing.” Prince Vasyl-Kostiantyn was perhaps the greatest defender of the Orthodox Church in the second half of the 16th century. Therefore, church delegations and famous church figures often visited the city. Among them was a representative of the Patriarch of Constantinople, Nikifor Kantakouzin, who, according to the legend, brought another famous icon to the city. You can scroll through this Bible online by clicking here.

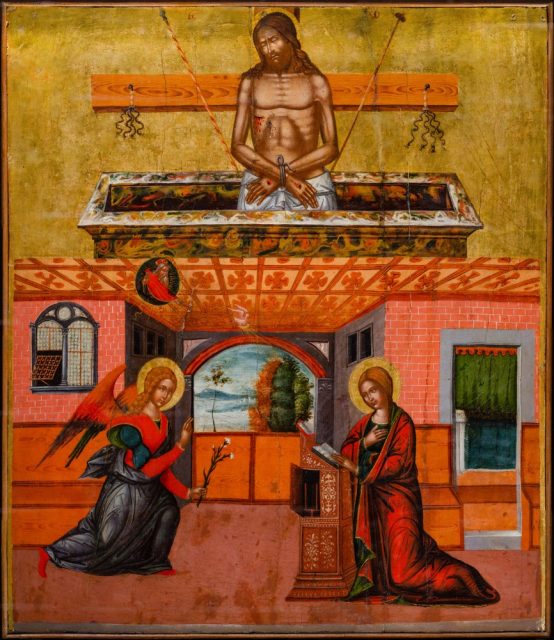

The Icon of the Annunciation.

The Icon of the Annunciation can be viewed in the museum hall. The icon is intricately divided into two sections, each conveying profound symbolism. The lower portion portrays the Annunciation, a pivotal event in Christian theology. On the left side, the figure of the Archangel Gabriel descends, bearing the divine message to the Virgin Mary regarding the birth of Jesus Christ, the Savior of humanity. Symbolising purity and grace, Gabriel holds a lily flower in his hand. Opposite him, Mary kneels in reverence beside a scriptorium—a medieval fixture used for reading and copying manuscripts. In the upper left corner, God the Father watches over the scene from heaven, extending his hand towards Mary. Meanwhile, at the centre, a dove—the Holy Spirit—hovers, representing divine presence and guidance. Above, the icon depicts the resurrection of Christ, emerging triumphant from the tomb, a potent symbol of redemption and eternal life. Mykhailo Hrushevsky referred to Vasyl-Kostiantyn Ostrogski’s activity as the “first national revival of Ukraine.” Thanks to the Prince’s initiative and backing, Orthodox culture quickly advanced to parallel Western European culture.

The portrait of Oleksandr Ostrogski.

The portrait of Oleksandr Ostrogski. This artwork exemplifies Sarmatian portraiture, renowned for its intricate detail and symbolic richness, typical of the nobility of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Originating from the myth of noble “descent” from the Sarmatian tribe, initially embraced by the Polish, it later found its way into the Ukrainian gentry. The portrait of Oleksandr Ostrogski showcases a round, full face with a downward-pointing moustache, exuding elegance. His right hand rests on his belt, while the left hand grasps the sword’s hilt. Draped in a reddish tunic resembling a red mantle adorned with black fur trim and precious clasps, his attire features a distinctive black fur hat with a red top and a large black brim embellished with a sizable black jewel clasp. The coat of arms of Ostrogski princes, displayed on a red background with gold accents beneath a princely crown, imparts an elite aura to the portrait. At the bottom, on a white field, the inscription reads: “Alexander Dux in Ostrog Palarinus Valhinia Parens Fundatricis,” denoting his title and role as the voivode of Volhynia.

The portrait of Prince Janusz Ostrogski.

The portrait of Prince Janusz Ostrogski. The portrait captures the essence of Janusz Ostrogski, a prominent magnate and politician of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Presented in profile with a quarter turn to the left, he exudes authority and influence. Adorned in a regal red tunic and a black fur mantle, symbolising his high status, Ostrogski’s right hand rests on a belt adorned with metal decorations, while his left hand holds a commander’s baton, signifying military prowess and leadership. The Ostrogski coat of arms and the initials “IPDOCIF” flank the portrait, with the inscription “Janussius Dux in Ostrog” at the bottom, denoting his princely title.

Janusz Ostrogski, the eldest son of Vasyl-Kostiantyn Ostrogski, distinguished himself through his education in Vienna and active engagement in the political and military affairs of the Commonwealth. From participating in Henry Valois’ coronation to defending Dubno from Tatar incursions and contributing to the Polish-Moscow War, Ostrogski held notable positions such as Castellan of Kraków, underscoring his influence among the magnates of his era. Though his legacy is complex, his political journey remains a compelling chapter in national history. The wealth and splendour of the princely court are confirmed by the several subsequent exhibits.

The five-arm bronze candelabra.

The five-arm bronze candelabra. Crafted in 1575 by Gdańsk master Friedelund Lukas under commission from the Ostrogski princes, the bronze five-arm candelabra is a majestic piece weighing 272 kilograms. Despite its weight, it exudes elegance, resembling a symmetrical tree with a broad crown. Akin to its counterpart at Dubno Castle, this candlestick stands on three lions, echoing the symbolism found on the tombstone of Kostiantyn Ostrogski in the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra.

The portrait of Beata Kostelecka.

The portrait of Beata Kostelecka. This female portrait intricately captures the elegance of Beata Kostelecka’s attire and accessories. She is depicted in profile, her head turned slightly to the right, wearing a sumptuous black dress with puffed sleeves adorned with opulent golden embroidery. Noteworthy is the embroidered collar, symbolising courtly traditions. Adding to her allure are a delicate cap atop her head and three strands of pearls adorning her neck. In her hands, she holds a small roll of paper, possibly signifying education or patronage. The inscription at the bottom of the dark background identifies her as “Beata Kostelecka Eliae Ducis in Ostrog Conjunx” (Beata Kostelecka, wife of Illya Ostrogski, prince in Ostroh). Beata’s life was marked by intrigue and drama. Born into the family of a royal favourite, she was raised at the court of Queen Bona Sforza. Her marriage to Illya Ostrogski and the birth of their daughter Halshka unfolded against the backdrop of the tumultuous “Magnificent Century.” After their wedding at the royal court, the young couple arrived at Ostroh, their ancestral estate. However, their marriage was short-lived. In 1539, they attended the wedding of Isabella Jagiellon and the Hungarian King John Zápolya. During the knightly tournament held as part of the festivities, where Ilya participated directly, he was thrown from his horse by Prince Sigismund-August. This incident led to Ilya’s death on August 19, 1539. Later that same year, in November, the widow Beata gave birth to their only daughter, Halshka (Elisabeth) Ostrozka. She would later become a benefactor of the Ostroh Academy, supporting educational initiatives spearheaded by her uncle.

The portrait of the “Unknown in the Red Coat”.

The portrait of the “Unknown in the Red Coat” from Ostroh, dating back to the latter half of the 1600s, offers a glimpse into the opulence and influence of its subject. This enigmatic figure, renowned for his distinctive red coat, epitomizes luxury and authority within the societal norms of that era. Serving as a poignant emblem of our Renaissance, the artwork captures a lifelike psychological portrait: the piercing gaze and austere countenance hint at a disposition of power, keen intellect, and uncompromising character. These traits are meticulously reflected in the intricately detailed red coat, symbolising wealth and dominance during that epoch. Moreover, the significance of the red hue extends beyond mere aesthetics. With Hernán Cortés’ introduction of cochineal dye extraction, the colour red gained prominence across Europe, becoming synonymous with nobility and authority, as elegantly portrayed in the portrait of the “unknown.” The distinctive “Cossack” hairstyle further enriches the composition, serving not only as a hallmark of Cossack fashion but also as evidence of its prevalence among the nobility, highlighting the symbiotic relationship between Cossack culture and the aristocracy. Despite the passage of time, the identity of the depicted individual remains shrouded in mystery. Contemporary researchers increasingly lean towards the hypothesis that it may depict Bogdan Suslo, a courtier of Janusz Ostrogski, associated with the legendary tales of feasting in Ostroh.

Portraits depicting the princely Ostrogski family and their court serve as a rich repository of insights into a pivotal era in Ukrainian history. These artworks not only capture the physical likeness and demeanour of historical figures but also offer glimpses into their refined tastes, social standing, and cultural predilections. Across centuries, the Ukrainian socio-political elite, epitomized by the Ostrogski princes, bore significant societal and military responsibilities. Their active involvement in campaigns and battles was instrumental in solidifying their privileged status within society.

These “warrior nobles” demonstrated their right to lead both their people and the state apparatus through their military exploits, thereby establishing and consolidating their influence and authority. The nobility exuded by these figures is palpable in the portraits, where meticulous attention to costume details, elegant poses, and facial expressions all underscore their elevated social standing and cultural sophistication. This elite stratum played a pivotal role in shaping early modern Ukrainian society and indirectly contributed to the formation of a distinct Ukrainian national identity, thereby becoming an integral part of Ukraine’s cultural and political heritage.

Through a careful examination of these portraits, we not only unravel chapters of history but also gain fresh insights, liberated from the myths and propaganda perpetuated by the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union.