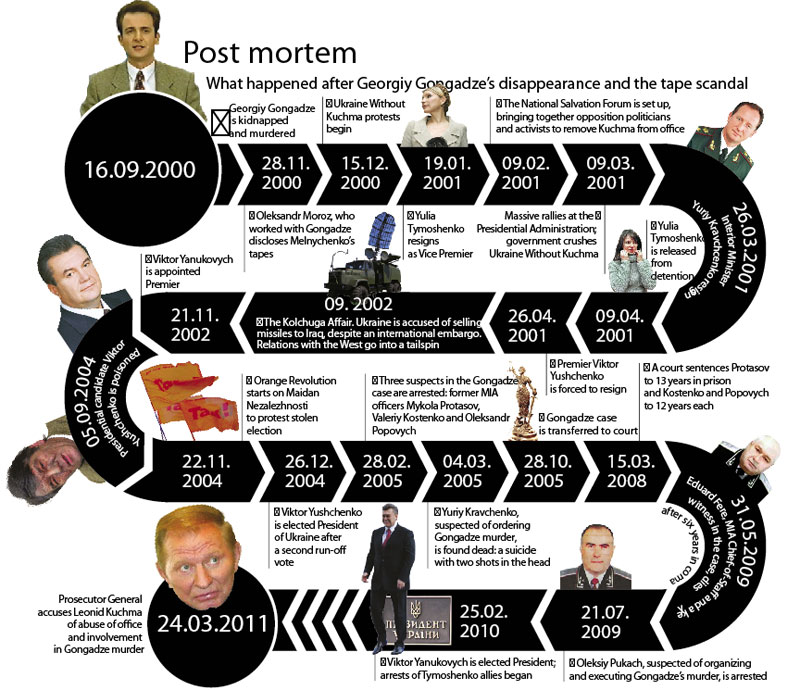

A new act in the play called “The Gongadze Affair” has taken the media by storm. Ukrainians immediately forgot about buckwheat, growing utility bills and rising food prices—even Yulia Tymoshenko’s long-anticipated trip to Brussels and her passionate speeches about dictatorship coming to Ukraine. All this has paled by comparison with the question buzzing around the entire nation: who will go to jail—or not?

The show’s scriptwriters have done a good job, there’s no question about that: they tossed their media megabomb with perfect timing and can now expect the audiences to keep watching mesmerized for some time to come. Yet, all this is at a very distant orbit from the central purpose for which the entire show was actually planned.

Launching a combination

Ukrainians are extremely discontent, social tension is growing as the deficit surges, and mere white noise alone cannot distract voters from their daily concerns. They can listen endlessly to stories about fighting corruption and growing GDP but nobody believes any of it after a visit to the nearest store. This kind of stuff can keep voters distracted for two or three days. An investigation and arrest are expected to have a longer run. This looks all too much like a well thought-out, nicely staged middlegame combination.

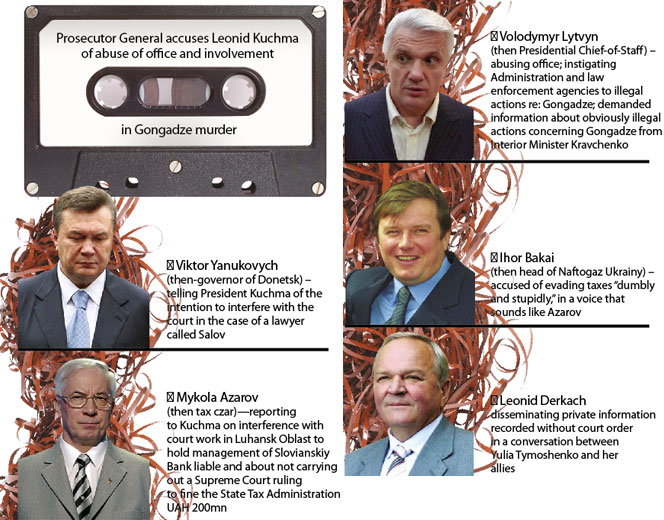

It is obvious from the way the prologue has been played strictly according to script that the play is backed by plenty of financial, organizational, media and other resources. Rumors have it that, in addition to Leonid Kuchma, Volodymyr Lytvyn and other people could also be brought to court. Yulia Tymoshenko has even suggested that Mr. Kuchma’s son-in-law, Viktor Pinchuk, is under pressure and more.

This media fog will likely continue. Yet, that’s all it really is: a fog. Simultaneous protests suit the script to establish social tension. The issues, the broad implementation, and the cynical approach to those involved all hint at who is directing from behind the stage. It has all the markings of the same people who orchestrated Kuchmagate I, back in 2000-2001. Then, too, the options for Ukraine’s government were suddenly very limited and any hopes of progress in relations with the West killed.

Continuous options…

The public, meanwhile, is being tossed red herrings to skillfully switch its attention. But the closer one looks at them, the more obvious their false nature becomes. Take the Pinchuk angle. It’s fairly easy to take his media and pipe-making empire away from the ex-President’s son-in-law. Both Ukraine and Russia offer plenty of similar stories. Maybe somebody even wants to do so, but lacks the reach. But to do so would cause so much trouble and lead to such predictable consequences that it isn’t worth the effort.

Firstly, Viktor Pinchuk is an international player. He is known in influential Western financial and political circles. As his father-in-law famously wrote, Ukraine is not Russia: Kyiv can’t even risk imagining that which Moscow easily allows itself. A step like this would be catastrophic for Ukraine, especially the financial sector, even if it’s not immediately apparent. Who’s going to invest in Ukraine after an attack this aggressive? Especially, since Pinchuk has no direct connection to the Gongadze case. The legal implications for Kuchma are not entirely clear: indeed, it’s not obvious whether a court case will happen at all. As a political figure, the one-time president has no value whatsoever, so discrediting him offers few political points. If the government takes it too far, people will just feel sorry for the victim. So the fusillade risks being a blank.

Secondly, if Kuchma goes to a public trial—and this is the only available option—, when he finds himself up against the wall, the former president could start saying things weren’t at all in the script. And then those running the show could find themselves with a caricature of the Reichstag Trial on their hands, where morally the future head of the Comintern, Georgiy Dimitrov, who was charged with arson in 1933, switched from being a defendant to being a plaintiff. Stalin wisely took into account the mistakes of Germany’s Parteigenosse and did his best to avoid this in the purges of 1937–1938. Obviously, the current government lacks the leverage that the best friend of soviet sports fans had—and Ukraine today is not the USSR then. This—and the fact that Viktor Pinchuk is hardly faint of heart and has enough clout to protect himself—makes the Pinchuk scenario very unlikely.

Volodymyr Lytvyn is a different matter. The leash he is held on is already too short. But the problem is that his party, especially its regional branches, is increasingly discontent with the role of something running underfoot with Party of the Regions. Mr. Lytvyn already complained about this in a recent speech to PR activists—not that this bothers PR, but they hardly need more opposition. So, they just tell the right people not to play with fire. An experienced politician like Lytvyn also knows that he could well be sacrificed as a stringer in any play to demonstrate how equal everybody is before the law.

A coup?

Thinking that the government wants a fine performance of “The Triumph of Justice” and “Just Desserts for the Guilty,” not only in the tragedy of Georgiy Gongadze, but in many other affairs, would be completely naпve. Nobody in Ukraine believes this. What is happening now has all features of a coup d’état. But without seizing the Winter Palace, the Bastille or the Baltic marines, the theatrics of it are different and the director seems to have considerable applying them in Ukraine.

This time it looks like the director’s has found an entry point in an extremely nasty struggle inside the President’s inner circle. Much ink has been spilled over how many folks were very unhappy with the way Mr. Yanukovych handed out posts after his victory. The President’s attempts to put all influence groups at an equal distance from himself have also failed: he ended up having to make his choices anyway, moreover under visible pressure from outside the country, where other folks thought that the redistribution of power in Ukraine did not meet their expectations, either.

Lo and behold! various scandals are back in the limelight. But, of course, the goal of this coup is simply to gain influence over the President. If he understands this and has entered into complicated relations with various interest groups, the audience could have some exciting entertainment in store. The intermediate goal is the President—and not necessarily the current one. The final goal is to run Ukraine in the right direction. To deprive a nation of its sovereignty is a complicated task and takes time. Meanwhile, elections are drawing closer and preparations have already started.

All this looks well-scripted and nicely performed, so far. And the director has several different acts up his sleeve, keeping in mind what Helmut von Moltke once said, “No plan survives contact with an enemy.” So far, the President has been persuaded to make some dramatic moves, partly by fuelling his desire for revenge over 2004. In this situation, subjective and situational aspects and motives do not matter much. More importantly, such a major contretemps among Ukraine’s top politicos risks escalating to a real war, easy to start but hard to finish, as the Roman historian—and politician—Gaius Sallustius Crispus once put it.

In short, there is no guarantee that the bullets will hit only the planned targets. A society that trusts no government is fatal and a State cannot survive like this for long. Did the instigators and organizers of this conflict understand or anticipate that they were establishing an extremely dangerous precedent for themselves, in the first place? If they really want to purge those in power, they are acting against themselves. But if they are trying to use the judicial noose against their rivals, they should remember the many historical examples of how this could end. Under different circumstances, a process like Kuchmagate can be turned against the scriptwriters and backstage directors. Is that what this witch hunt is for? Not likely.

Purging those in power by running a coup under the guise of judicial and prosecutorial procedure can succeed. The actors can change. But household budgets could fail to match market prices. As Napoleon put it, “War is a series of unexpected events.”