This year marks the 20th anniversary since Ukraine’s symbols of state were officially approved. They are young but have deep historical roots

THE ORIGINS OF NATIONAL SYMBOLS

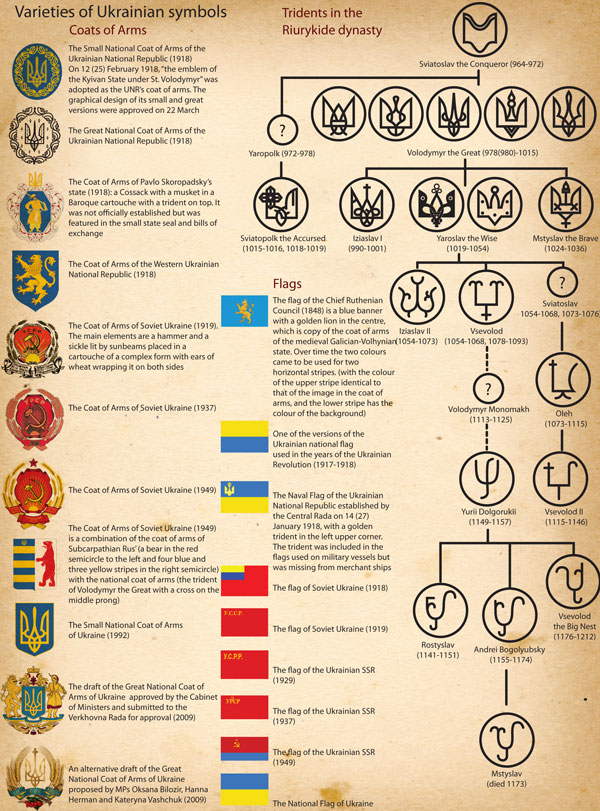

Ukraine’s national coat of arms, the trident, goes back to the times of Kyivan Rus' and the Rurik dynasty. Its original meaning has become obscured over time and now there are dozens of academic papers to explain it. Some see it as a code for the Greek Βασιλεύς(Vasileus, or tsar), and others believe it represents a church candlestick, a gonfalon, the portal of a church building, an anchor, a hawk, the upper part of a sceptre or three natural elements. One thing is clear: the trident was featured in princes’ seals in pagan days, so it should not be viewed through the prism of Christianity. At the same time, it could not be a purely pagan symbol, because it continued to be used long after Kyivan Rus' was Christianised.

The Ukrainian national flag as a symbol for the masses (unlike banners that were identified with specific individuals or groups) emerged together with the Ukrainian nation which had a clear desire for political self-determination, societal self-consciousness and a standard language. The Chief Ruthenian Council, the first political organisation of Ukrainians in Galicia founded in May 1848 in Lviv, was instrumental in establishing the blue-and-yellow flag. On 2 June 1848, it was presented at the Slavic Congress in Prague and was quickly and widely adopted by Ukrainians in Galicia and later in regions along the Dnieper, thus turning into a true national symbol.

The words to the national anthem ‘Shche ne vmerla Ukraina’ (Ukraine Has Not Yet Died) was written in autumn 1862 by the poet Pavlo Chubynsky and the music was composed a year later by Greek-Catholic priest Mykhailo Verbytsky. The first public presentation took place in 1864 in the Ukrainian People’s Theatre in Lviv. The song became immensely popular and so widely known that Chubynsky’s friends had to defend his authorship and prove that it was not a folk song.

Ukraine’s national symbols were conclusively established during the Liberation Struggle of 1917-21 when the national emblem and flag were legally fixed and the anthem obtained de facto recognition (see Varieties of Ukrainian symbols).

After Ukraine lost its statehood, these three national symbols were not forgotten or lost. On 15 March 1939, when Carpathian Ukraine in Transcarpathia was proclaimed an independent Ukrainian state, it adopted them as its state symbols. The UPA and underground fighters also used them, and after the Second World War they became truly national symbols of all Ukrainians in the “free world.”

SOVIET SYMBOLS

During the period of over 70 years of Soviet rule, the Ukrainian SSR had its own state symbols which differed little from the Soviet state's symbols and underscored its dependent condition: a red flag with the abbreviation “USSR” or a hammer, sickle and star, and a narrow blue strip was added in 1949. The Ukrainian SSR did not have its own anthem for a long time. One was produced — also in 1949 — by composer Anton Lebedynets and poet Pavlo Tychyna.

Ukrainian national symbols were banned in the USSR, and their use was punished as “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.” Heorhiy Moskalenko and Viktor Kuksa were convicted of this crime when they raised a self-made blue-and-yellow flag in Kyiv on 1 May 1966 (see The Ukrainian Week, Is. 27/2011).

THE TURBULENT PERESTROIKA DAYS

Opportunities for reviving national symbols came only with the start of democratic changes in the USSR. The trail here was blazed by the Baltic states – Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania adopted their pre-war flags as national (but not yet state) symbols in 1988. Moldovans, Georgians, Armenians and Azeris followed their lead.

The conservatively minded leadership of Ukraine, however, protected the Soviet symbols. The Commission of the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR for Patriotic and International Education and International Relations held a meeting in summer 1989 and decided that the Soviet symbols could not be abandoned during perestroika. For example, writer Yuriy Mushketyk, who is now a Hero of Ukraine, noted resentfully that certain individuals carried blue-and-yellow flags during Shevchenko Days in Kyiv. “We should not replace the proletarian colours of our flags, the communist symbols … [because] the people’s government fought and put the ideas of the Great October into life under them,” he emphasised.

Leonid Kravchuk, chairman of the Commission and head of the Department for Ideology in the CC CPU, summed up the prevailing position: “The blue-and-yellow colour in the history of our Republic, to say nothing about the Bandera era in western regions of Ukraine, is compromised. Everyone has concluded that it is tainted with fighting and resistance against our red-and-blue flag… These dirty and bloody symbols are alien to the Ukrainian people. They have always been equated with exploitative statehood.”

ON THE WAY TO ADOPTION

Despite the convulsive ideological gestures of the party nomenklatura, Soviet symbols in Ukraine were doomed. In spring 1990, blue-and-yellow flags were raised in Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil regions after the opposition forces led by Rukh obtained a majority of seats in the local councils there. On 23 July, the Ukrainian national flag appeared next to the Soviet Ukrainian red-and-blue flag in front of the Kyiv City Council.

In the last years of the Soviet Union, the issue of national symbols in Ukraine was more than a debate about colours and emblems. It became a kind of battlefield between two models of identification and visions of future development. Society essentially split into the hammer-and-sickle camp and the supporters of the trident. The former demanded keeping Ukraine in the USSR, while the latter called for independence.

After the failed Moscow coup, opposition MPs solemnly brought a large-sized blue-and-yellow flag into the session hall of parliament on 23 August 1991. (The National Flag of Ukraine holiday was instituted in 2004 to commemorate this event.) Ukraine declared its independence the next day. The operation of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was banned in Ukraine and the Communist Party of Ukraine temporarily suspended its activities.

The utterly compromised Communist Party symbols were soon seeing their last days. On 4 September 1991, under the insistence of Verkhovna Rada Speaker Kravchuk, who quickly read the situation, MPs passed a resolution to raise “the historical blue-and-yellow flag that symbolises the peace-loving Ukrainian state through the colours of a clear sky and a field of wheat” over parliament. As of 18 September, this flag could be used in all official events. Parliament completed the rehabilitation process after the 1 December 1991 referendum by establishing the blue-and-yellow banner as Ukraine’s national flag on 28 January 1992.

Settling on the national emblem turned out to be more complicated. Most MPs agreed that it had to include a trident but disagreed on its specific design. Parliament adopted a compromise resolution on 19 February 1992, and fixed this historical symbol as Ukraine’s Small Coat of Arms, which was supposed to become the main element of the Great Coat of Arms. The existence of two coats of arms is fixed in the Constitution, which says: “The Great National Coat of Arms of Ukraine shall be established incorporating the elements of the Small National Coat of Arms of Ukraine and the Coat of Arms of the Zaporizhia Host”. However, the country still do not have a Great Coat of Arms.

In more than 15 years since the Constitution was adopted, four government commissions were formed to prepare and hold competitions to design the Great National Coat of Arms, but only a handful out of hundreds of submissions reached the stage of a draft bill.

A somewhat similar situation arose in adopting the national anthem. The Presidium of the Verkhovna Rada adopted only Verbytsky’s music as the score for the anthem in the intersession period on 15 January 1992. It was played, but not sung, for 11 years. (The anthems of Russia, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Spain were also wordless.) The text was finally adopted on 6 March 2003. The communists, inspired by the restoration of the Soviet anthem in Russia, had tried to do the same in Ukraine, but the Ukrainian parliament passed a bill sponsored by President Leonid Kuchma. The words of the anthem consisted of the first verse and the refrain of Chubynsky’s song. However, the first line was slightly modified: “Ukraine has not yet perished, nor her glory, nor her freedom” became “Ukraine’s glory and freedom have not yet perished”.

Today, we are still in the process of adopting our state symbols. We still lack a law on the National Flag and the National Coat of Arms. Their use is so far regulated by parliament resolutions. We need to finally put the issue with the Great Coat of Arms to rest and fix one standard for the colours of the flag. This is especially true of the upper stripe which varies from sky blue to navy blue.

THE DANGER OF REINCARNATION

Unfortunately, in the 20 years Ukraine has been independent, its national symbols have failed to consolidate society. Despite its chief mission of uniting the country’s citizens regardless of their nationality, religion or political preferences, they are still viewed by many as a modern invention and are used mechanically, without any emotional link to history. On the one hand, there has been a positive trend since the fall of communism in that society no longer has negative or openly hostile reaction to the blue-and-yellow flag and the trident unlike in the early days of independence. On the other hand, a change of colours does not mean that Ukrainian political elites, which evolved from the old party nomenklatura and the red proletariat, truly accept the national symbols as markers of our separation from Soviet past.

There have been increasingly frequent attempts in the past two years to restore the old Soviet symbols. The communists are no longer alone in their cause. In May 2010, the Verkhovna Rada passed a law on the Victory Flag, and a wave of attempts to revive totalitarian symbols swept across Ukraine. Contrary to a Constitutional Court ruling which pronounced these actions illegal, red banners are hung out next to blue-and-yellow flags on the local council buildings in eastern Ukraine, and not only on May 9, but also to mark days when the Nazis were driven out of individual settlements, as well as on June 22, the day when Germany attacked the USSR. For example, this practice was recently introduced on the regional and city levels in Luhansk Region.

With the current government promoting communist symbols, we can only hope that the more nationally conscious football fans will be rooting for our national team under blue-and-yellow, rather than red, flags.