Lviv resident Sviatoslav Litynsky has sued Samsung Electronics over the fact that its washing machine does not have labels in Ukrainian. He bought a Samsung washer from an online retailer. When it arrived, he saw that the labels on the control panel were only in Russian. He sent the washer back to the store and sued Samsung for UAH 105. “I spent five hryvnias on the trip to return my purchase, and the remaining 100 hryvnias is moral damages. The very fact that they violate legislation and don’t make labels in Ukrainian should prompt the public to take a closer look at how international brands and corporations treat the Ukrainian language,” Litynsky says. The trial is scheduled for March and is set to become a precedent that will force businesses to give the matter some thought.

READ ALSO: Russification Via Bilingualism

Litynsky’s lawsuit is a vivid example of what ordinary Ukrainians are doing to defend their linguistic rights. Another effective method is voting with the hryvnia, and it is being practiced by many citizens. For example, in autumn 2012, a victory was scored over the Roshen corporation. Roshen had replaced Ukrainian-language labels on its packaged sweets with Russian ones, citing economic concerns: it exported its products to the Russian Federation, so why not use a language understandable in both countries. However, Russian-language labels triggered a storm of outrage in social networks and an information campaign against Roshen. In November 2012, Ukrainian-language labelling was partly restored.

FEEDBACK: Activists email companies requesting them to respect the rights of Ukrainianspeaking consumers. Many accept the demands eventually

Another example is the language of service in restaurants, cafés, and eateries. In January 2013, the Tanuki restaurant came under scorching criticism: its waiters spoke only Russian, which triggered a scandal of nearly international dimensions. Members of the “Don’t Be Indifferent” movement raised alarm after the staff of a Tanuki restaurant rudely refused to speak Ukrainian to a female client. The Internet community urged for a boycott of the restaurant. In late February, a reporter for The Ukrainian Week went to Tanuki and found that despite the menu still being only in Russian, the waiter spoke Ukrainian as he accepted the order.

BOYCOTTING AS A COUNTERMEASURE

“I have been ignoring products without Ukrainian-language labels as well as restaurants without a Ukrainian-language menu for nearly three years now,” says Dmytro Dyvnych, a private Kyiv-based entrepreneur. He is an activist of the “They’ll Get it Anyway!” movement on Facebook which will soon be marking its first anniversary. Its members send appeals, letters and complaints demanding that businesses respect the interests of Ukrainian-language consumers and use Ukrainian when they operate in Ukraine.

In addition to restaurant service and product labelling, other problematic areas are the Internet and software. “My observations show that Ukrainian is most often ignored in retail chains, Internet businesses and delivery services. None of the brands represented in Ukraine whose products involve the use of software can be considered fully oriented towards Ukrainian consumers,” Dyvnych says. Most software companies whose products are present on the Ukrainian market have Ukrainian-language versions. However, Ukrainian is often not available on electronic gadgets, even if they have officially registered IMEI numbers. For example, Kyiv resident Andriy Svitly bought an HTC desire X but decided not to keep it because the smartphone did not have Ukrainian as one of its supported languages. The Internet store where the purchase had been made agreed to take it back or replace with another smartphone. When Andriy called the Ukrainian office of HTC, he was told that the language package of this model did not include Ukrainian and advised him to try and tinker with the gadget himself. The official explanations of IT businesses boiled down to the claim that they did not have the ability to dynamically introduce Ukrainian in all models or on websites.

READ ALSO: When Language Matters

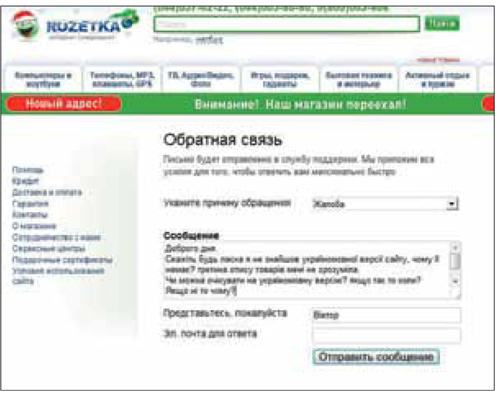

Moreover, many corporations lack Ukrainian-language versions of their websites or communicate in Russian online. The blacklist of the “They’ll Get it Anyway!” movement has a category entitled “Facebook page not in Ukrainian” which includes around 90 international and Ukrainian companies many of which are notable brands that have been on the Ukrainian market for a long time. These include, among others, ASUS Ukraine, Becherovka Ukraine, Brocard, Chrysler Ukraine, Dove Ukraine, Honda Ukraine, JEEP Ukraine, KIA.UA, Lancome Ukraine, Levi’s Ukraine, Mercedes-Benz Ukraine and Nokia UA. According to activists, some business representatives have reacted positively. For example, about 20 of them (FIAT Ukraine, Toyota Ukraine, Hyundai Ukraine, Philips UA, PocketBook and others) have accepted the demands. The category of companies that do not have a Ukrainian version of their websites also includes dozens of businesses, such as the Rozetka online appliance store, the Foxtrot chain, Sportlife, Oriflame, Faberlic, Citroёn, Semki and Air France. Members of social movements who engage in active correspondence with these enterprises note that some of them have promised to fix things by the end of the year, while others flatly refuse to introduce Ukrainian in their online resources. Tellingly, a Hewlett Packard representative replied that the company was not planning to open a Ukrainian-language version of its website and cited the fact that Russian had been raised to the status of a regional language. Outraged consumers launched a protest on Facebook, urging others to boycott HP products, and were finally heard by the company, which promised to take their position into account.

ECONOMIC ARGUMENTS

Marketing expert Roman Matys, who founded the “They’ll Get it Anyway!” movement, believes that most brands represented in Ukraine have Russian-language website start pages because of a stereotype: “For some reason, businesses doubt the purchasing power of Ukrainian-language consumers. Moreover, market specialists assure that the website of a brand which operates in Ukraine will be readable in the entire territory where Russian is used. This evidently has an effect on decision makers, so marketing budgets are being spent inefficiently. If you look at it through the eyes of a consumer, why would an auto group that sells its cars in Ukraine target the entire Russian-speaking space? Its cars will not, in any case, be purchased in Belarus or Tatarstan because these countries have their own offices for the same brand!” Matys offers businesses an argument that debunks the myth about Ukrainian-language marketing being inefficient: “The most money is spent on TV commercials. When I ask why spend so much on supposedly inefficient Ukrainian-language commercials, I usually draw a blank.”

READ ALSO: A Slippery Slope

However, after the so-called law on languages was passed, the situation changed for the worse. Article 26 of the law specifies that “advertisement statements, messages or other forms of audio and visual advertisement products are executed in the state language or in another language of the advertiser’s choice.”

“Unfortunately, this law prompts [advertisers] to turn a blind eye to the language of advertisement and install billboards with Russian texts. Therefore, this situation leaves only one way to influence players who ignore language – refuse to buy their products that are not labelled in Ukrainian,” Artem Zeleny, CEO of GreenPR, says.

Representatives of the “They’ll Get it Anyway!” movement have tried to calculate the effect of consumer protection of the Ukrainian language. According to Matys’ estimates, brands that ignore Ukrainian-speaking consumers are losing up to five per cent of their sales volumes even now. “When this level rises to 30%, many businesses will begin to pay attention to the interests of people who want to live in a Ukrainian-language environment,” he sums up.

Pay attention. On its Internet page, the “They’ll Get it Anyway!” movement posts visual proof of the rights of Ukrainian-speaking consumers being violated.