The fiscal and economic problems facing unreformed post-soviet countries in recent years have grown worse because a significant portion of the working-age population is evading taxes and social contributions. Despite the switch to a market economy and capitalism, they all continue to live inside a soviet bubble: countless social benefits and “free” education and medical services are something that the state is “supposed to” provide. Yet too many able-bodied individuals don’t contribute to the funds that are supposed to be financing all this. Even those who do, often only do so on a portion of their real incomes—and that a very small one.

Taxing the freeloaders

The first “tax on freeloaders” was instituted last year by Belarusian President Alyaksandr Lukashenka. In April 2015, he signed a decree according to which all able-bodied citizens living on the territory of Belarus who are unemployed and have not paid any taxes for six months will have to pay a fee worth 20 basic units, currently €200 or be subject to fines or even suspended sentences requiring them to carry out community work.

This year, the idea was picked up by Russia. This past spring, Deputy Labor Minister Andrei Pudov announced that his Ministry was discussing the possible introduction of a tax on able-bodied individuals who were officially unemployed. When this announcement caused a stir, the Ministry’s press service clarified that such a tax was only being discussed “at the expert level and in the context of studying the impact of this practice in Belarus.” Still, at the end of September, Russian Vice Premier Olga Golodets announced to the upper house of the RF legislature that a bill that would make unemployed citizens pay for their use of social infrastructure was being drafted, after all.

Still, it’s actually Ukraine that faces the worst problem in this area, with nearly half of its working-age population neither contributing to the Pension Fund and other social services, nor paying taxes to the budget that finances their medicine and education.

Twixt past and future

In soviet times, the priority was to provide for as many of the basic needs of the population as possible by redistributing state resources through what was called social consumption funds. The Ukrainian SSR Constitution of 1978 included, beside the provision of free services and social benefits, Art. 23, which declared that the state “with the purpose of more fully satisfying the needs of the soviet people, shall establish social consumption funds. With the broad support of community organizations and labor collectives, the state shall ensure the growth and fair distribution of these funds.”

In soviet times, the priority was to provide for as many of the basic needs of the population as possible by redistributing state resources through what was called social consumption funds. The Ukrainian SSR Constitution of 1978 included, beside the provision of free services and social benefits, Art. 23, which declared that the state “with the purpose of more fully satisfying the needs of the soviet people, shall establish social consumption funds. With the broad support of community organizations and labor collectives, the state shall ensure the growth and fair distribution of these funds.”

Such social funds were the instrument for solidarity funding of a majority of most people’s needs. For instance, the social consumption funds ensured that education and professional development were free, as were medical services, pensions and student allowances, and vacation pay, that rest cures to sanatoria were either free or deeply discounted, that children had pre-school institutions that took care of them, along with a slew of other benefits and discounts.

These funds were generated by the citizenry, whose incomes were under the state’s watchful eye as everyone, without exception, worked for the state or in the ‘collective’ sector, meaning enterprises and organizations where any income earned by the workers was automatically transferred to the state. In the USSR, it was a crime to “evade socially useful work” because then the state would lose the ability to control a significant portion of the added value that its workers were supposed to be generating on its behalf.

RELATED ARTICLE: The daily life of cartels: On competition and state anti-monopoly policy in Ukraine

Soviet law, in fact, made it a crime punishable by incarceration up to two years or correctional labor between six and 12 months if a citizen “evades socially useful work and lives on non-labor-generated income more than four consecutive months or for four months during the course of a single year and has been issued, in this regard, an official warning about the unacceptability of such a lifestyle.”

Still, in a capitalist system and market relations, things are very different. With the owners of assets and employers generally private individuals and companies, while the state is now just one of many players, contributions into the “social consumption” funds are based on deductions from reported incomes. Moreover, there is no obligation to work or criminal investigation if it is avoided.

Instead, we have the far more effective principle of mutual dependence on participating in contributing to these social funds—in the form of insured medical, pension and other state and private funds—and strict liability for evading the payment of taxes to budgets at all levels of government. Based on this model, when someone fails to contribute to the various social funds, they and their family members have no right to draw on the services that are financed by such funds—even if that person were to die as a result.

Moreover, in a capitalist economy, such funds play a much lesser role because it replaces soviet collectivism with individualism, which means that everyone tries to give away as little as possible of their income to any common funds and to independently manage as much as possible of that private income. And that is certainly true of most Ukrainians today. However, among Ukraine’s citizens, this attitude is, paradoxically, not accompanied by an awareness that if you want something to be free, that is, medicine, education, decent unemployment benefits, sick leave and pensions all financed by public funds, then this has to be done by contributing 50% and more of your own real wages. The other option is to reduce the role of social mechanisms for funding education, healthcare, pensions and other social benefits and increase the role of the individual’s own efforts.

RELATED ARTICLE: An expert on Ukraine's anti-monopoly policy about changes in it today and the role of oligarchs in limiting its capacity

What we can see today in the attitudes of most Ukrainians can only be called social schizophrenia. People stubbornly hang on to the soviet mentality that expects the state to pay for all their needs in these areas, but equally categorically reject the notion of giving up a major portion of their incomes for public funding to pay for all these benefits.

Double indemnity

The Consolidated Single Contribution (CSC) that was introduced on January 1, 2011, replaced four separate contributions: to the Pension Fund, the Unemployment Insurance Fund, the Temporary Disability Fund, and the Workplace Accidents Fund (known as Workers’ Compensation in some countries). This contribution was cut steeply as of January 1, 2016, from 36-43% to 22%, of which around 18% goes to the Pension Fund and 4% to the State Service for unemployment and other social benefits to cover those same cases.

Since Ukraine does not have medical insurance and public funding of healthcare will continue to come out of the budget, personal income tax (PIT) until such time as medical insurance is fully instituted, the PIT is a kind of quasi-insurance payment in support of these services for the time being. The PIT is around 18%, but healthcare services actually cost the government a bit more than 50% of its PIT revenues: in 2017, UAH 77bn has been earmarked for this purpose out of anticipated PIT revenues of UAH 150.6bn.

RELATED ARTICLE: The prospects of Ukraine's agricultural sector

The real problem is that, since the CSC was cut back, PIT revenues don’t even cover the shortfall in the social insurance funds that are funded by the CSC. The shortfall is expected to reach UAH 172.9bn in 2017. Based on the current number of contributors, even just to cover expenses for the social insurance funds and public funding of healthcare, the CSC or PIT rate would have to be raised from the current 40% to at least 46-47%. The only real solution is to radically increase the tax base.

A numbers game

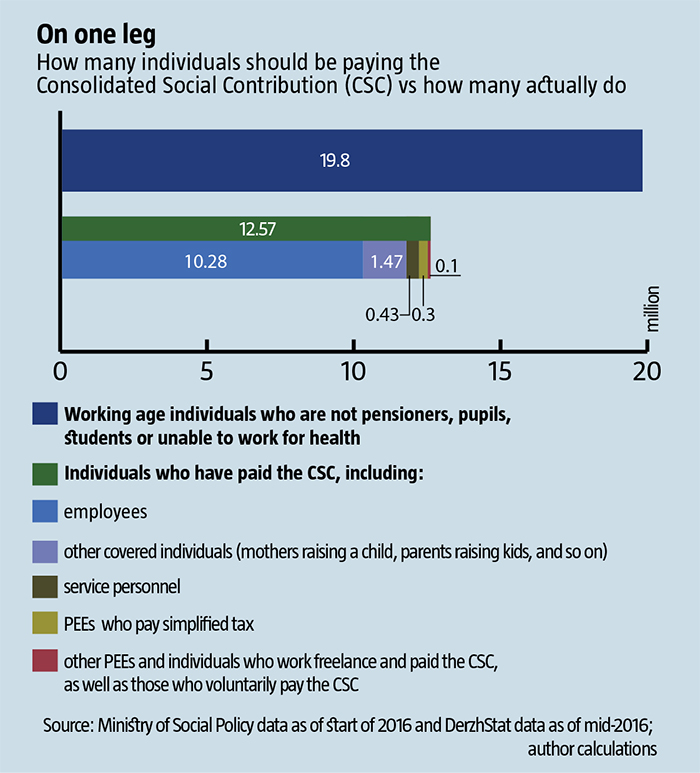

The Ministry of Social Policy data from the beginning of QII 2016 illustrates just how critical the situation is, in the correlation between those receiving pension benefits and those who pay the CSC. Currently, some 9.35mn pensioners across Ukraine receive this benefit due to their age, 1.4mn due to disabilities, 0.73mn due to the loss of the breadwinner, 0.66mn due to years of service, and 0.1mn for other reasons. But only 10.28mn individuals, including 0.61mn who are sole entrepreneurs,[1] pay the basic pension contribution. In addition, there are 0.43mn insured service personnel. Of the 609,000 FOP covered by the simplified tax, only 431,100 are insured and 130,000 of those are of retirement age or disabled. Of the 609,000 FOP in the general tax system and effectively self-employed, 225,000 did not contribute to the Pension Fund. Finally, 1.49mn Ukrainians belong to other categories of nominally covered individuals, but also did not contribute at all to the Pension Fund, including stay-at-home moms, foster parents, and so on.

For comparison, Social Policy Minister Andriy Reva says that Poland has 22mn contributors based on the same demographics. In Ukraine, there should be approximately the same number paying the CSC. According to Derzhstat, the state statistics bureau, only 17.35mn Ukrainians were registered as “economically active individuals of working age.” The actual number of able-bodied Ukrainians is much higher, because official statistics only include as “economically active” those who “are working or actively looking for work and prepared to start working within two weeks.”

RELATED ARTICLE: How the ban on land sale affects small owners of land, farmers and big agribusinesses

Moreover, “working-age” individuals means men and women age 15 through 59, so it’s hardly surprising that, in Ukraine’s situation, the 10.9mn who are “economically inactive” include mostly pensioners, pupils, students and individuals who cannot work for health reasons. Still, among them are 2.2mn of those who are “engaged in managing the household and are supported,” another 0.25mn of those “who don’t know where and how to begin looking for work” or “who think there aren’t any suitable jobs available.”

This already adds up to 19.8mn Ukrainians of working age who are not pensioners, pupils, students or unable to work for health reasons. This number pretty well matches the number of payers of social contributions in neighboring Poland, which has approximately the same population as Ukraine without the population of the temporarily occupied territories. The difference is that nearly half of this group in Ukraine contributes nothing to the budget or the social funds while at the same time expecting that they and the members of their families should have free medical and educational services, as well as at least a minimal pension in the future.

The social contributions and PIT base for individuals includes two groups of the employed: 5.1mn full-tie employees in the private sector at enterprises with at least 10 employees, and nearly 3.5mn public sector employees, whose salaries are paid by the budget. Another nearly 1.5mn are engaged in micro businesses where there are fewer than 10 employees or are registered sole entrepreneurs. The number of self-employed Ukrainians who pay taxes and social contributions is insignificant. Moreover, most FOPs paying under the general tax system and self-employed individuals are in fact not paying the social contribution.

Freddy Freeloader and the gang

The problem is that a fairly broad range of individuals are considered formally employed in Ukraine when, in fact, they are not. Based on this, the state is delaying the resolution of a large-scale problem with hidden unemployment. Millions of people refuse official status as unemployed and the support for real job searching that goes with it. For instance, the largest group of nominally employed in agriculture is around 2.5mn country dwellers who have family farmsteads and gardens. Given the problems with finding jobs, especially in rural areas, they actually grow, or have the potential to grow a certain amount of produce for their family’s to live on and sometimes a portion of that is sold. In most cases, however, we are talking about a scale that is far from the one needed in order to consider this kind of activity as a viable source for keeping families alive.

At the same time, most of these people have undeclared income because they are working under the table in other towns in Ukraine or abroad, forming a major portion of the multi-million strong Ukrainian migrant labor force. Some of them may also be taking care of households or keeping the livestock while other members of the family work for money.

This does not mean that their problems with getting jobs that are more effective and stable should be taken off the agenda.

But they simply have no basis to avoid paying, together with other Ukrainians of working age, into those funds that will finance, at one time or another, medical services and pension benefits for them and members of their family, and unemployment or disability benefits. Otherwise, these benefits will have to be paid by the 11mn Ukrainians who do make these contributions, even though they are often no better off than those who work under the table.

RELATED ARTICLE: Finance Minister Oleksandr Danylyuk on tax reform

The notion that the oligarchs will pay for this has no basis in reality. The budget, let alone social funds, is based on the contributions of all citizens. For instance, the latest report from the Finance Ministry for 2015 shows that revenues from the profit taxes of all corporations, public and private, were only UAH 39bn. The bulk of revenues came from ordinary citizens: the PIT contributed UAH 90.8bn, while the CSC brought in another UAH 185.7bn.

The fact that those Ukrainians who pay their CSC and PIT end up “sponsoring” not just their own needs but the needs of those who are avoiding paying these taxes tends to kill incentive, leading them to resent: “Why should I pay for benefits that others get anyway, even without contributing a single kopiyka?” and to understandably cut the number of contributors who keep paying without getting their fair share even more.

This vicious cycle can be stopped in a number of ways. One would be to refuse any state benefits to those who are not contributing to the Pension Fund, for example. But this is unlikely: if such voters end up at risk of dying of hunger and the cold, enough populists will pop up to lobby for such “freeloaders” to get paid at least some minimal amount of benefits from the state budget, including medical services and pensions—even if these individuals never paid a kopiyka of PIT or CSC to the budget.

Making the system fairer

A large portion of individuals who officially are unemployed and are not contributing to the Pension Fund or paying the PIT are revealed by tax inspectors when they review companies on a regular basis. Just over January-August 2016, some 105,000 unofficial employees were discovered this way. For instance, in August, a review of a company making hanging chairs in Bakhmut County of Donetsk Oblast showed that, although it officially reported only four employees, in fact nearly 130 were working there.

Still, this kind of approach is unlikely to resolve the problem at a systemic level. Such companies may be forced to officially hire their under-the-table staff and pay the necessary payroll deductions, but a month or two or five months later, these same people will be laid off while the company itself closes down and reopens under a different name, and so on.

The government needs instruments that will at least minimize the incentives to work in the shadows—even if they are unlikely to eliminate them altogether. The inevitable measure here seems to be the requirement to pay a minimal CSC and PIT, as the PIT has ended up “subsidizing” the CSC after it was significantly reduced. Eventually, mandatory medical insurance will be introduced, whose contributions will completely cover those basic services that are provided at no cost. The contribution to this kind of insurance should be at the level of at least 50% of the current PIT rate.

RELATED ARTICLE: Reforms in Ukraine's banking sector

These contributions need to be made by all working-age citizens, whether they are working for pay or taking care of their household, living off rental fees or interest on deposits, or have other income from property that they own. To be employed or to simply make these contributions are everybody’s business. For instance, if one of the spouses considers that it makes more sense for their partner or one of their parents to stay at home and take care of the household rather than be hired somewhere outside the home, that person should pay their minimal CSC and PIT for them. This would guarantee that this person receives the minimum in pension benefits, medical services, and so on, so that this burden is not transferred to other taxpayers and CSC payers.

After all, even if someone is relatively well off today and has income from properties or is a member of a wealthy family, there’s no guarantee that their life won’t change significantly in five, 10 or 25 years and they might need public assistance in the form of a pension or basic medical services. For humanitarian reasons, it will be impossible to refuse them these benefits. Contributions above the minimal amount, of course, would be treated as voluntary.

Any changes in financing medicine will have to go both ways and motivate medical professionals to have a better attitude towards their patients. Since they will be making mandatory contributions through the PIT and medical insurance, individuals should then have the right to independently determine which state or private facilities they wish to frequent, based on their contribution to the funding.

Propositions to cover shortfalls

Today, there are about 39 million people living on territory under Ukraine’s control. Average annual budget spending per person for medical services is about UAH 2,000, based on the 2017 Budget Plan. This means that a family of 3-4 that has gone over to private medical facilities because of the unsatisfactory services provided by public ones has no way to make use of its UAH 6,000-8,000 share. If we only consider those families whose members are paying the PIT, then we are talking about an even larger sum. Of course, going to private clinics on a regular basis means paying considerably more than these sums. But at least part of this cost will be covered by the amount that such families are currently simply “donating” to public clinics that they are forced to avoid.

MinFin’s draft 2017 Budget provides UAH 77.0bn for healthcare, UAH 161.6bn to subsidize the Pension Fund, and UAH 11.3bn to support the unemployable, which adds up to UAH 249.9bn. Yet only UAH 1506bn is projected to be taken in from the PIT. In short, the shortfall in direct contributions from the working population is already UAH 99.3bn. If those 10 million Ukrainians who currently are paying nothing by way of PIT or CSC, or are paying them on nominal salaries that are below the minimum wage, were to make at least the minimal contribution to both, more than 80% of this deficit would be covered. The Social Policy Ministry proposes eliminating the remaining shortfall by relieving the Pension Fund of responsibility for paying out certain pensions, such as those based on years of service and other social benefits that the state has delegated to it.

RELATED ARTICLE: An attack on NBU Governor Valeria Hontareva: What's behind the discreditation campaign

There remains one serious problem. A lot of time has been wasted and there are millions of citizens in Ukraine today who have not contributed to the Pension Fund for decades, yet who expect the state to provide them with at least a minimal pension when they retire. Even if they start to contribute today, many of them will never attain the necessary years of contribution to get a pension at this point. At the same time, at the same time, it would be a social injustice to pay them even the subsistence minimum for pensioners that will also be paid out to a large portion of those who paid in all those decades.

In this situation, in order to not increase the retirement age across the board because of a particular group of citizens, a higher benchmark should be set for those who have not been contributing the necessary amount of time to the Pension Fund. If there is no indicator that there was a health issue—because that’s a different case where the need to receive a pension can arise well before retirement age—, the individual who is not vested because of not contributing long enough can and should be provided with pension benefits at a level that reflects their previous earnings and continue to work, if the pension isn’t enough to live on. The standard minimum pension can then be given at 70 or even 75, if no other health issues prevent them from working in the meantime.

In the meantime, increasing requirements to pay both PIT and CSC for those individuals who are either not contributing at all or are registered as officially unemployed should be accompanied by an active policy of incentivizing the creation of new jobs, especially in the manufacturing sector, particularly in depressed regions. The Ukrainian Week has more than once discussed the kinds of measures that might lead to this. If not, the country will be faced with a situation where a significant proportion of those who are genuinely unemployed will find themselves in a hopeless situation.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook

[1] Physical persons who are registered enterpreneurs, called FOP in Ukrainian.