Moscow’s propaganda persistently distorts the history of Ukrainian military elites. According to Russian propagandists, whose narratives shift to suit their agendas, these Ukrainian elites either never existed or had exclusively what they call ‘Great Russian’ or even ‘Moscow’ origins from the start. The Ukrainian Week is launching a series of articles on the history of the Ukrainian military community in the medieval and early modern periods, free from Russian imperial stereotypes.

The roots

The discussion about the origins of the Ukrainian military community can begin with the roots of the Ukrainian political class and the state itself. This question was so important to the author of the first text of Ukrainian history, “The Tale of Bygone Years” chronicle, that he placed it in the title: “From where did the Rus’ land come, who first began to rule in it, and from where did the Rus’ land originate?”

The chronicler who worked on The Tale of Bygone Years at the beginning of the 12th century depicted the origins of the Rus’ state in this way: The Vikings, or Varangians—referred to as Rus’ in the chronicle—arrived among the Slavs as carriers of advanced administrative technologies at the invitation of the Slavs themselves. They were led by three brothers: Rurik (circa 830–879), Sineus, and Truvor. From the shores of the Baltic Sea, they swiftly moved south into Slavic lands. That same year, Askold and Dir, two of Rurik’s “boyars”—though notably not his relatives—were already established in Kyiv. They arrived in a city with its own history and founders, unrelated to the Varangians. Askold and Dir remained in Kyiv until 882, even conducting a military campaign against Constantinople. They were eventually overthrown and killed by Oleg (known as Helgi), a relative of Rurik and guardian of his young son, Igor (known as Ingvar). The Tale of Bygone Years asserts that all subsequent legitimate Rus’ princes, who had proliferated by the early 12th century, descended from Rurik.

The chronicle’s account of Ukraine’s early political history continues to spark fierce debates. It’s of particular interest because it clearly postulates the cultural interactions between Viking newcomers and Slavic natives, which led to the formation of the Rus’ state, ruled by Rus’ princes. Since princes cannot exist “in a vacuum,” this also implies the existence of Rus’ military elites.

The Slavs

Byzantine authors describe the Slavs who inhabited Central-Eastern Europe from the 6th to 9th centuries as a colourful tribal community of hardy, unpretentious warriors unburdened by civilisation, wealth, or advanced military technologies. Emperor Maurice, in his military manual “Strategikon,” wrote in the late 6th century: “They are both independent, absolutely refusing to be enslaved or governed, least of all in their own land. They are populous and hardy, bearing readily heat, cold, rain, nakedness, and scarcity of provisions”. Their habitat – “nearly impenetrable forests, rivers, lakes, and marshes, and have made the exits from their settlements branch out in many directions because of the dangers they might face…”.Their weapons reportedly included light spears, shields, and poisoned arrows, and their lives were a constant struggle with both neighbours and nature. However, they were extremely confident on their own turf.

Modern historiography often stereotypes the ancient Slavs who lived in what is now Ukraine as peace-loving. This view is supported by the small number of archaeological finds of weapons, the simplicity of their construction and decoration, and the Slavs’ supposed inability to engage in external expansion. However, anthropological comparisons with modern tribal societies cast doubt on this “peacefulness.”

Applied studies do not confirm the supposed “non-militancy” of tribal societies in Africa, Oceania, and South America. Instead, it highlights high levels of inter-tribal and even intra-tribal violence. These societies often engaged in ongoing raiding wars for ecological niches, aiming for the mass extermination of enemies regardless of gender and age. The lack of clear legal mechanisms for conflict resolution led to a culture of blood revenge, decimating entire settlements, clans, and even tribes. According to 20th-century anthropologists, such conflicts resulted in the deaths of 24% to 35% of the male population aged 15-49, depending on the region. The low level of military technology did not mitigate these losses. This is likely what the chronicler referred to when mentioning “feuds” and “clan uprisings.”

Image: Slavic man with axe and shield, 7th–9th century | Princeton University Art Museum

Due to the high level of internal tribal violence and constant military and economic pressure from nomadic peoples in the Black Sea steppes, the Slavs had little time for distant campaigns or expansionist ambitions. This doesn’t suggest pastoral peacefulness; rather, quite the opposite. Byzantine and Latin writers from the 6th to the 12th centuries regularly hinted at the brutality of ancient Slavs, mentioning widespread traditions of human sacrifice, including children. Therefore, it’s unlikely that customs on the banks of the Dnipro River were any more humane than those in the Amazon rainforest. Prince Igor’s death at the hands of the Drevlians, triggered by his demands for tribute, underscores this point. Leo the Deacon recounts that in 970, several infants were strangled during funeral rituals for Sviatoslav’s warriors near Dorostolon (now in Bulgaria – ed.). It’s no coincidence that the “Rus’ka Pravda” (The Truth of the Rus’) legal code addresses blood revenge in its first article, offering monetary compensation for killings as a more effective alternative to vendettas at the time.

The Vikings

In the 9th century, the Varangians, known as Vikings, ventured to the shores of Ilmen, Ladoga, and the Dnipro River in search of new trade routes and opportunities for profit. Their expansion followed a clear geographical trajectory: from the North to the South, from the Baltic to the Black Sea. It was during this period that Arab and Western European sources started to identify these newcomers as “Rus’.” The primary trade goods of the Rus’ were slaves and plundered items. Success in commerce depended on a steady supply of both, destined for sale in Eastern and Byzantine markets.

Image: The relief depicts a Viking warrior in full gear, including a spear, sword, axe, scramasax, helmet, and shield, and while the unknown artist omitted chainmail, the rest of the equipment strongly suggests that the character’s prototype possessed it.

The Rus’ boasted advanced military technology. Frankish swords and ‘winged spears’ wreaked havoc on unarmored Slavic natives, while metal armour, typically chainmail, instilled confidence in battle. Their ships offered remarkable mobility for the time. However, despite their military prowess, the Rus’ faced numerical disadvantages, and even their most potent weapons often struggled against superior numbers until the advent of firearms. Hence, cooperation with local Slavic elites became crucial.

Caesar Maurice offered a practical solution to this dilemma. Soon as the Slavs “have many princes, who are in constant discord among themselves, it is not difficult to draw some of them to one’s side through negotiations or gifts… and then attack the others, since their continuous enmity prevents them from uniting under one ruler.” Simply put, the emperor’s advice boils down to pitting one leader against another and profiting from the conflicts of tribal warfare. This strategy was commonplace in the slave trade until the 19th century. Byzantine Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus, in the mid-9th century, vividly recounted the Rus’ expedition down the Dnipro River with slaves and goods bound for Constantinople. Along the way, they faced not only the formidable Dnipro rapids but also the threat of marauding nomads, highlighting just some of the challenges on the arduous journey from the Varangians to the Greeks.

“Similarly, much of the expansion to the east was driven by trade and was probably also mostly peaceful. Although the establishment of towns along the Rus` river system may have taken place to facilitate long-distance trade, the introduction of a Scandinavian elite ruling over the mixed population is unlikely to have been completely peaceful, a view supported by the presence of a significant number of warrior graves,” Gareth Williams, curator of the British Museum’s renowned exhibition “Vikings: Life and Legend,” explains. Despite the legendary nature of the accounts in “The Tale of Bygone Years” regarding the beginnings of Rus’ in the mid-9th century, the overall narrative of the chronicle aligns with archaeological evidence.

The melting pot

The genealogy of the earliest Rus’ princes is shrouded in antiquity. In Viking societies of the era, there existed a tradition known as the ‘sea-king,’ a title attainable by any noble descendant who owned a ship and commanded a crew. It is plausible that the legendary figure Rurik emerged from such a context.

Viking expeditions served as a natural refuge for ambitious and warlike individuals facing misfortune at home, and not all participants were of Scandinavian descent. Among the colourful characters aboard longships were exiled monarchs, including Pepin II (823-864), the deposed King of Aquitaine, who was dubbed a ‘companion of Danish pirates’ after being forcibly tonsured by his rival, Charles the Bald. The ‘Annals of Saint Bertin,’ the oldest Western source mentioning the ‘Rus’,’ record that upon the first opportunity, Pepin abandoned the monastery and returned to secular life, renouncing his vows and joining the Normans, integrating himself among them.

At the outset, the Rus’ population is believed to have been rather limited. Ship construction constraints determined the size of their crews, while medieval production and logistical limitations influenced the number of ships they could deploy. Hence, the accounts in the “The Tale of Bygone Years” suggest that the early Rus’ princes made extensive use of local resources for military endeavours and mustered diverse forces—including Varangians, Rus’, Polans, Slavs, Krivichs, Tivercians, and Pechenegs—appear credible.

The Scandinavian newcomers and Slavic natives quickly found common ground in their shared pagan faith, rooted in polytheism, oral tradition, and a tendency for daily violence, which facilitated communication between them.

The relationship between the Pechenegs and the Rus’ wasn’t always hostile. As noted by Constantine Porphyrogenitus, there were instances where the Rus’ traded horses with the Pechenegs. It’s worth mentioning that communication between Kyiv and Constantinople only occurred when there was peace between the two groups. Interestingly, the author of “The Tale of Bygone Years” was well aware of the distinct military practices of the Normans and nomads, particularly the reliance on mounted archery. This is evident from the account of an arms exchange between the Rus’ voivode Pretych and the Pecheneg prince beneath the walls of Kyiv: “The Pecheneg prince gave Pretych a horse, a sword, arrows, and he gave him armour, a shield, a sword.”

It’s important to bear in mind that the unification of these tribes and peoples was driven by the demands of the Rus’-Byzantine trade, especially in the vicinity of Kyiv. Emperor Constantine addresses this in the section ‘Of the coming of the Rus’ in ‘monoxyla’ [dugout boat made from a single piece of timber – ed.] from Rus’ to Constantinople’.

“The ‘monoxyla’ which come down from outer Rus’ to Constantinople is from Novgorod, where Sviatoslav, son of Igor, prince of Rus’, had his seat, and others from the city of Smolensk and from Teliutza and Chernihiv and Vyshegrad. All these come down the river Dnipro and are collected together in the city of Kyiv… Their Slav tributaries, the so-called Krivichians and the Lenzanenes and the rest of the Slavonic regions, cut the ‘monoxyla’ on their mountains in time of winter, and when they have prepared them, as spring approaches and the ice melts, they bring them on to the neighbouring lakes. And since these lakes debouch into the river Dnieper, they enter thence on to this same river, and come down to Kyiv, and draw the ships along to be finished and sell them to the Rus’. The Rus’ buy these bottoms only, furnishing them with oars and rowlocks and other tackle…”

The transition of Rus’ from successful engagement in continental trade with Byzantium to political initiatives was a matter of time. Princes were surrounded by armies. Therefore, the Normans, who presented themselves as princes or kings and had political plans regarding Slavic lands and peoples, had to invest in armed forces. Thus, the princely retinue emerged. These military-commercial collectives traditionally had a diverse composition, both ethnically and socially. Data on the size of princely retinues are scarce and contradictory. Researchers speculated, based on chronicle information, about the number of women that Prince Volodymyr the Great provided to his warriors in service, as well as the size of payments to the retinue. It turned out that during the pagan period of his biography, Volodymyr had 400 fighters, while his son Yaroslav, while in Novgorod, had more than a hundred. The Tale of Bygone Years of 1093 reports that Prince Sviatopolk Iziaslavych had 800 warriors at his disposal, but even this number was insufficient to launch a campaign against the nomadic Cumans.

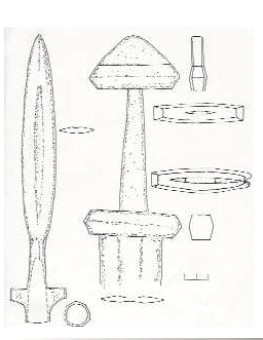

Image: The sword and spear, dating from the 8th to 9th centuries, are of Carolingian origin and were found in modern Cherkasy and Rivne regions.

However, these armed forces proved sufficient for Rus’ princes to periodically harass the Byzantines with maritime raids, aiming to secure more favourable commercial conditions. Oleg’s intervention led to the signing of a detailed agreement on Rus’-Byzantine economic cooperation in 911. By 944, this agreement underwent revision after several years of armed conflict instigated by Oleg’s protégé, Igor. Notably, many of the Rus’ signatories to both documents bore Western names such as “Bruni, Hroald, Gunnfast, Freystein, Ingjald, Thorbjorn…” indicating a Western influence. These texts outlined the rights and conditions for Rus’ merchants residing in Byzantine territories, suggesting that Rus’ Vikings had yet to formulate international political ambitions at that time.

From raiding to politics

Prince Sviatoslav (died in 972), son of Igor, stands out as the first among the Rus’ leaders to reveal political aspirations. Summoned by the Byzantines to aid in their conflict against the Bulgarians, he mustered an army resembling the formidable forces of Viking ‘great armies’ active in Western Europe and embarked on the Danube in 968. According to the Byzantine chronicler and eyewitness to the Rus’ invasion, Leo the Deacon, the invaders were notably numerous, potentially numbering in the thousands, akin to their Western counterparts. The Slavic names borne by both Sviatoslav and his sons indicate the depth of interactions between the Normans and the Slavs. Furthermore, the engagement of the prince’s warriors in Slavic-style bloody rituals, such as the sacrifices near Dorostolon, suggests the prominence of Slavic individuals within Sviatoslav’s ‘great army’.

However, the army travelled by ships and engaged in battle using the ‘shield wall’ formation, adhering closely to Viking customs. The Deacon’s depiction of the initial clash between the Rus and the Bulgarians mirrors narratives of Viking expeditions. “While he was sailing along the Istros and was hastening toward a landing place on the shore, the Mysians perceived what was going on, and, after organising themselves into an army composed of thirty thousand men, they went out to meet them. But theTaurians disembarked from their transport ships, and, after vigorously presenting their shields and drawing their swords, they cut down the Mysians on all sides.”

Leo’s reports on Svyatoslav’s campaign in Bulgaria from 968 to 971 reveal that the Rus were equipped with swords and spears, donned mailshirts and helmets, and wielded large shields that reached the ground—typical gear for the European military elite of that era. While Leo directly mentions that the Rus were not trained in cavalry combat, he also recounts a mounted skirmish involving a robust Taurian [Leo’s term for the Rus newcomers – ed.] and a Byzantine nobleman. Additionally, he describes a cavalry charge by Sviatoslav’s horsemen near Dorostolon, though it was ultimately unsuccessful. This irony noted by the Byzantines underscores a significant shift underway within the Rus’ military elite—a shift common to all Viking conquerors who transitioned from sea raiders to landowning knights. Similar transformations occurred in the Norman Duchy, founded by descendants of the Vikings in the latter half of the 10th century.

Svyatoslav’s campaign in Bulgaria started off on a high note—within a year, he had seized control of northern and eastern Bulgaria and ousted the local ruler, Boris II. Buoyed by these victories, the prince issued an ultimatum to the Byzantine emperor, demanding a withdrawal from the European territories into Asia under threat of invasion if refused. This marked the first instance in history where a Rus’ prince and his retinue placed political dominance over the conquered territories above commercial gains.

Image: Meeting between Emperor John Tzimiskes and Sviatoslav I of Kyiv | The Madrid Skylitzes manuscript, 12th century.

However, Sviatoslav’s campaign came to a tragic end. In 971, Emperor John I Tzimiskes blocked him in the heavily fortified Danube city of Dorostolon. Despite having a smaller army compared to the Byzantine forces, Sviatoslav’s troops suffered several painful defeats, primarily due to the superior Byzantine cavalry. The prince himself narrowly escaped death in battle, saved by his reliable armour. Yet, the Norman tradition of the old order also influenced the outcome. Impressed by the Rus’ martial prowess, the emperor opted to negotiate a treaty for their safe return home with plunder and provisions rather than continue military confrontations. However, on the arduous journey back, Sviatoslav fell into an ambush set by former allies, the Pechenegs, and died there.

The tragic conclusion of the “last Viking ruler of Kyiv” underscored to Sviatoslav’s heirs and their military cohorts that the traditional Viking approach of “fight, loot, retreat, and trade” was no longer effective. With new political aspirations came the need for fresh political, cultural, and military adaptations. Integration into the new Christian world took precedence over confrontation. The reactions to this shift had to be navigated by the armed Rus’ elites and their leaders, the princes, becoming the central storyline in Ukrainian history during the pre-Mongol period.