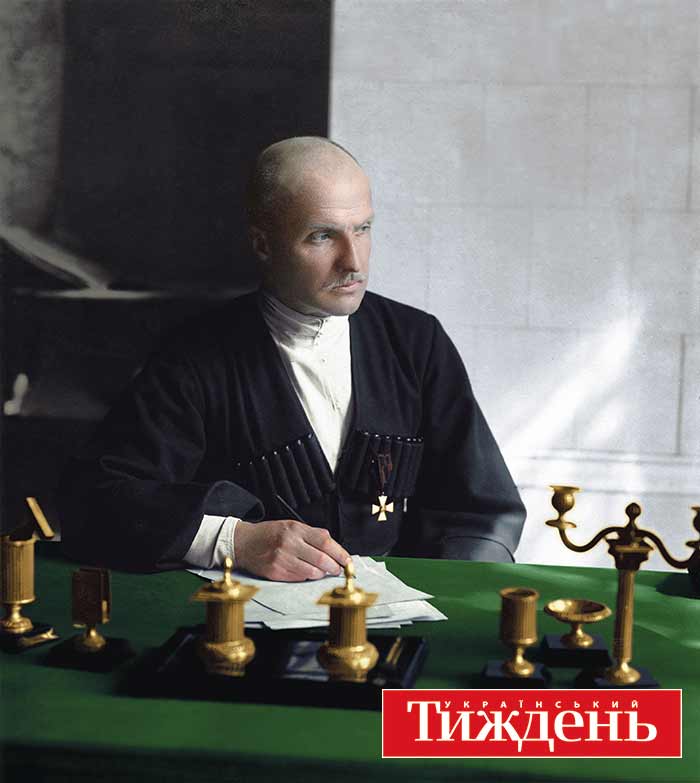

In his “Missive to the entire Ukrainian nation” of April 29, 1918, Pavlo Skoropadsky started by saying that “the previous Ukrainian leadership,” meaning the Central Rada, “had failed to build the state of Ukraine because it was quite incapable of doing so. Rioting and anarchy continue in Ukraine, economic collapse and unemployment increase with every day, and this once richest Ukraine is now faced with the terrible specter of famine. The current situation, which threatens Ukraine with a new catastrophe, has deeply shaken the working masses who had stood up and demanded in no uncertain terms that a proper government be immediately established that was capable of ensuring its people peace, law and the opportunity to engage in fruitful work. As Ukraine’s faithful son, I have decided to respond to this challenge and to temporarily take on all the powers. With this missive I declare myself Hetman of All Ukraine.”

In deciding to establish the nation’s statehood in its traditional historical form, Pavlo Skoropadsky was taking on a very difficult task: a hetmanate, unlike the socialist orientation of the Ukrainian Central Rada, was supposed to serve the interests of the entire nation, an not one particular class or social group. As it turned out, the Hetman did not meet with understanding or support from the liberal-socialist majority of Ukraine’s political class on this thorny path. Skoropadsky and the Hetmanate he established were the subject of biased political depictions for a very long time – baseless accusations of treason, unconfirmed negative myths about his actions, and outright falsification.

One of theses myths can often be heard even today, stating that the Hetman was a federalist and that his political actions in 1918 were driven by a desire to restore pre-revolutionary Russia. In fact, his position was the outcome of a deep conviction that Ukraine needed to establish state institutions rationally and assert its independence. In 1918, the main threat to Ukraine’s independence was very clearly bolshevism. Hence the historic mission announced by the Ukrainian State – to unite around it all the colonized states that were newly independent and were threatened by Russian bolshevist expansion – became a major objective of the Hetmanate. In the process of state building in Ukraine, Skoropadsky made anti-communism a core doctrine, which carried with it the effort to establish a union with the peoples who had been yesterday’s imperial colonies.

Moscow saw the threat to Russia’s establishment of a unitary state not in the slogans of national patriotic speeches and declarations by Ukrainian socialists but in the actual existence of a Ukrainian State. The most profound assessment was made by Vladimir Lenin, when he said that the continuing existence of Skoropadsky’s Hetmanate would shrink Russia’s state to the size of 15th century Muscovy.

RELATED ARTICLE: Lilly, The Hetman's Daughter

The question whether Skoropadsky favored federation with Russia or not is primarily connected to the so-called “federative missive,” and it requires the Hetman’s political position to be more broadly interpreted – something those who oppose him, of course, don’t do. From the very start of his political activity and until the appearance of this document, Skoropadsky never showed any inclination towards federalist arrangement. On the contrary, he more than once talked about the viability of the prospects and development of a Ukrainian state. Indeed, Ukrainian socialists were supporters of the idea of a federation with Russia – and extremely consistent ones at that.

Even after the announcement of the Third Universal of the Ukrainian National Republic, they did not reject the idea of federation and looked at Ukraine as a component of Russia. In the draft UNR Constitution, handling foreign policy, making decisions around war and peace, commanding the armed forces, and more, were all delegated to the Russian central government. The Fourth Universal of the Central Rada announced an independent Ukraine – and still allowed for a return to the concept of federation at some future date.

In contrast to these positions Pavlo Skoropadsky used the term “federation” under the influence of different political events and in different contexts, but believed that any such union had to ensure the economic and cultural development of “the entire Ukrainian nation on a strong foundation of nation-state identity.” The publisher of the Hetman’s “Recollections” in the Russian language, Yaroslav Pelenskiy, was absolutely right in stating, “There is no historical basis for considering Skoropadsky a firm federalist simply because he used this word rather loosely.”

Despite using one term or another to speak about the future of the Ukrainian state, Skoropadsky built real institutions that determined the essence of the statehood of an independent Ukraine. For Ukrainian socialists, by contrast, state-building activity never really moved beyond mere political declarations. And yet, almost from the very start of the Hetmanate, the leaders of Ukraine’s socialist parties began preparing for a rebellion against the Hetman’s rule. In this way, they managed to wreck any constructive tendencies towards state-building in Ukraine.

Mykyta Shapoval and Volodymyr Vynnychenko, the two leaders of the rebellion against the Hetman – Shapoval called them the “machinists of the revolution” – effectively made its coming to the Ukrainian National Union inevitable. In his book, The Rebirth of a Nation,” Vynnychenko admitted that while they were preparing, it was “dangerous to speak of it” with certain members. In his memoirs it becomes obvious that “sympathy for this idea” was lacking among the majority of members of the UNU. When Vynnychenko first brought up such a proposal at a meeting of the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Social-Democratic Workers’ Party, it was rejected as a “pipe dream.” Indeed, when the Central Committee found out about the preparations for an insurrection, it began to demand that Vynnychenko answer on what basis he, as a member of the Committee and despite his decision, was undertaking this step “which could cast a shadow on the party and bring harm to the entire national project.” As he wrote later, Vynnychenko did not deign to offer the Committee an explanation. He announced that he was taking all responsibility on himself and, should no one be found to follow him, he would himself “go to the countryside and call people to rise up.” According to him, the only person in the union that understood the need for a military insurrection against the Hetman was Shapoval. “And our entire secret organization,” he wrote, “consisted of two men: M. Shapoval and I.”

Talks with the three leaders of the Ukrainian Party of Socialist-Federalists, Andriy Nikovskiy, Serhiy Yefremov and Kostiantyn Matsievych, proved fruitless. All three declared the idea adventuristic and refused to participate. There is other evidence that the Ukrainian National Union was, in fact, not properly informed about preparations for the uprising. It organizers did everything they could to manipulate public opinion, and waited for the opportune political moment that they could use to their advantage. And that opportunity came with Pavlo Skoropadsky’s missive about a federation between Ukraine and Russia.

The appearance of the “federative missive” was linked primarily to the position of the Entente towards Ukraine. During a visit by Dmytro Doroshenko to Switzerland, where he met with Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando, and Ivan Korostovets to negotiations in Jassy, Romania, it became clear that the Entente was not prepared to recognize Ukraine as an independent state and saw it only as a part of Russia. Under threat that Ukraine would be treated as an enemy state and insistence that the Hetman announce a federation with the future state of Russia, the Hetman issued his formal act of intent to establish such a federation. In fact, this step actually did not affect the separate existence of the Ukrainian state in any way but offered an opportunity to gain some time to form a regular Ukrainian army. This would have radically changed the alignment of military and political forces in Eastern Europe and ensure the further existence of an independent Ukrainian state, despite its poor foreign policy situation.

For Hetman Skoropadsky, the “federative missive” was a temporary tactical step of a diplomatic nature, forced by a shift in the military and political alignment in Central and Eastern Europe, a revolution in Germany and Austro-Hungary, and the unprecedented pressure of the Entente on Ukraine. At the same time, for Ukraine’s socialists and a large part of its liberals, a federative basis for relations with Russia was driven by absolutely other considerations. And this became to cornerstone of their political positions and the party platforms that formed the basis of their activities.

The Declaration of the Ukrainian State needs to be seen in light of the threat to Ukraine’s sovereignty that had arisen as a result of the ineffectual position of the leaders of the Central Committee. Skoropadsky’s Hetmanate, in fact, was an attempt to overcome the autonomist-federalist vision of relations between Ukraine and Russia that dominated the world views of the liberal-socialist majority of the political class.

The “federative missive” needs to be seen as a step to preserve Ukraine’s statehood under shifting political circumstances. It contained no suggestion that state institutions should be set up jointly with Russia. Being entirely declarative in nature, it contained no specific mention of the integration of the two countries. Hetman Skoropadsky was aware of the danger of the political pressure coming from the Entente but, as he announced in an interview with the editor of the Gazette de Lausanne, “against my own better judgment, I had to bow to the demands of our allies ands announce a federation with Russia.” This was the step that allowed Ukraine to continue to exist as a separate state.

RELATED ARTICLE: The Ukrainian Navy and the Crimean Issue in 1917-18

Skoropadsky wrote later that, under his administration, “Ukraine was not merely in the process of organizing, but was almost a fully established state: its economy was recovering, trade was growing intensely, rail traffic and other transport were almost back to normal.”

At the same time, the Hetman expressed his firm belief that the guarantee of peace in Eastern Europe, success in fighting the corruptive tendencies of extremist movements was the sense of nationhood. “Organized as a state based on a sense of nationhood, in line with the deep desires of all the people to govern themselves,” he wrote, “Ukraine will become the unshakeable support of that peace that the entire world is now seeking.” In this clear and concrete fashion, Pavlo Skoropadsky made absolutely clear his consistent position as a nationally conscious and convinced Ukrainian statesman.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook