The last three years have been extremely difficult and extraordinary for Ukraine and changes have touched every aspect of life here. Economically, the difficulty is not that Ukrainians have lived through a lengthy crisis, but that this crisis was not a classical one. Unlike the crisis-driven decline in overall demand in 2008-2009, this time, business and investors are running into the destruction of infrastructure by armed conflict and plain theft—the confiscation of assets in occupied Crimea and Donbas—, the loss of traditional markets and the search for replacements, and the need to eliminate the economic imbalances that have accumulated and stand in the way of a better future.

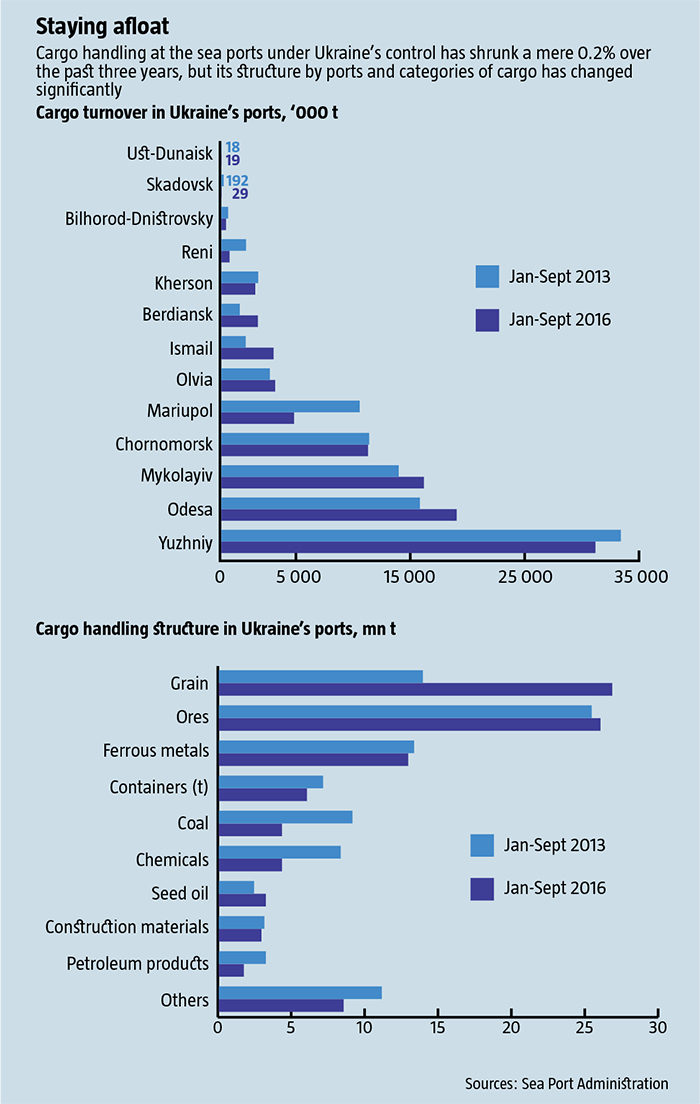

Developments in Ukraine’s seaports are a very good illustration of the economic trends of the last three years. Having lost their Crimean harbors and undergone a real logistic revolution due to the military, geopolitical and economic events going on, this sector has barely lost anything on key indicators and is now gradually focusing on plans for growth.

Ukraine’s ports: Working under capacity

Ukraine has 13 functioning commercial sea ports. Last year, they handled 145 million tonnes of cargo. According to data from the Port Authority of Ukraine (PAU), their turnover capacity is 51mn t of liquid cargo, 180mn t of dry cargo, and 3mn t of TEUs.[1] This means that the ports were working at only 23%, 59% and 16% capacity in 2015, low numbers that were driven by a series of bottlenecks in their various systems.

Of the handled volume, last year 72% of cargo went for export, 12% was being imported, 11% was in transit, and 5% was cabotage, that is, transferred between domestic ports by vessels from another country. The relative share of export to import cargo that is handled in the ports is based on the fact that raw materials, which Ukraine predominantly specializes in producing and exporting, is cheaper and heavier while the finished products that Ukraine imports and consumes are lighter yet more expensive because of their relatively higher added value. The small share of transit cargo suggests that there is untapped potential there. Since 2012, its share has shrunk by half from an already-low 23%, although even then it as far less than its potential. The problem, of course, is not just related to the stand-off with Russia, which is probably the main reason why transit cargo has gone down so much in the last-3-4 years, but in other, deeper issues.

RELATED ARTICLE: Ukrainian approach to paying taxes explained

When Russia took Crimea, it also took five ports, which handled 7.6% of Ukraine’s total cargo shipments. Since that time, the traditional routes for shipments have undergone noticeable changes. The occupied peninsula’s docks have lost pretty well all of their cargo traffic from mainland Ukraine and in 2014, their turnover fell by 67%. Eventually, Russia picked up the slack, amounting to 9.6mn t in 2015.

However, it’s not practical for the Federation to handle its cargo in Crimean ports because, first of all, the only land connection is to mainland Ukraine and Russians are avoiding transiting through Ukraine. Secondly, the Russian press reports that port fees in Crimean ports are three times higher than similar fees in Russian ports. The excuse provided is that they need to pay people wages. So of that volume, the biggest share, 7.8mn t, went to Kerch last year, although its documented capacity is only 6.9mn t. Prior to the takeover, the Kerch port had been working at 33-50% capacity. The Kerch harbor is being overused in order to supply Crimea, which from Russia’s point of view is an island, with all its basic needs. Cargo turnover is growing: in the first nine months of 2016, it had already handled 7.1mn t, which was 32% more than in the same period of 2015. Still, the remaining Crimean ports are barely surviving and if the current geopolitical situation doesn’t change, they are pretty much doomed. Since the international legal status of Crimea remains unresolved, the services of its ports will only be able to be used by Russians, for whom they are economically pointless.

Après le déluge, nous

Harbors in mainland Ukraine have also undergone major changes. The export orientation of cargoes that are handled in domestic poets has led the main indicators for these ports not only to maintain their levels but to even increase in the last two years: figures for 2016 show that they are back up to 2013 levels. For Ukrainian producers and exporters, it’s clearly more convenient to ship through Chornomorske or Odesa than to Constanta, let alone Novorossiysk. For some it may now be more expensive that it was when they could ship through Crimean or Azov ports, but that is unlikely to change, for now, leaving the two Ukrainian ports as the optimal solution. The same is true for imports.

As a result, mainland Ukraine’s ports have been almost to maintain the same level of cargo handling over the last three years. Of the millionaire cities, only Mariupol’s port has suffered serious losses, due to the difficulty receiving and shipping with a conflict zone just outside the city and Russia’s complete control over the Kerch Strait. In short, the decline in cargo handling volumes since 2013 at mainland Ukrainian ports due the economic crisis and a fall in production has been compensated by the reorientation of cargo flows from Crimea to these ports. This has helped the docks to not feel the crisis, for all intents and purposes, and to continue to draw up and implement development plans.

RELATED ARTICLE: The daily life of cartels: On competition and state anti-monopoly policy in Ukraine

The balance of cargos handled in these ports has also shifted significantly. In tandem with the general trend towards growth in the farm sector, the volume of grain and oils handled has dramatically risen. The destruction of Donbas has led to a decline in the handling of coal, coke, chemical and metallurgical products, but growing volumes of foodstuffs have compensated for these losses, tonnage-wise. The volume of petroleum and petroproducts has gone down as these shipments were reoriented towards deliveries to neighbors that are accessible by surface transport—Belarus, Poland and Romania—, while transit traffic has gone to Russian ports.

Fixing what’s broke, financing a future

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s seaports have a number of problems and bottlenecks that are being worked on all the time. Moreover, this started well before the Euromaidan. The main changes took place in 2013, when the Law “On seaports in Ukraine” was adopted and then a Strategy for the Development of Ukraine’s Seaports for the period through 2038 was drawn up. At the beginning of 2014, prior to Viktor Yanukovych’s absconding, a separate strategic plan was approved for each of the harbors. At the time, rumors had it that these changes were meant to foster the “privatization” of the ports by the Yanukovych “Family.” Fortunately, the Yanukovych regime never got that far, but the various transformations launched by it set up a chain reaction of some extremely necessary reforms.

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s seaports have a number of problems and bottlenecks that are being worked on all the time. Moreover, this started well before the Euromaidan. The main changes took place in 2013, when the Law “On seaports in Ukraine” was adopted and then a Strategy for the Development of Ukraine’s Seaports for the period through 2038 was drawn up. At the beginning of 2014, prior to Viktor Yanukovych’s absconding, a separate strategic plan was approved for each of the harbors. At the time, rumors had it that these changes were meant to foster the “privatization” of the ports by the Yanukovych “Family.” Fortunately, the Yanukovych regime never got that far, but the various transformations launched by it set up a chain reaction of some extremely necessary reforms.

For starters, this law separated the administrative and commercial functions of the sea ports, the latter being delegated to the Port Authority of Ukraine, as a state enterprise that has a branch in each of the ports and manages them all. The PAU also owns the marine shelves, hydrotechnical structures, docks, approaching roadways and service networks. The commercial side is handled by a state enterprise of the same name and stevedoring companies whom the DAU leases out port infrastructure. With the opening up of access to stevedoring operations for private entities, this segment has seen competition grow and investment projects to expand the quantity and variety of port capacities. The logical consequence of all this has been the gradual loss of market share for state stevedoring operators handling cargo.

Right now, there are a number of bottlenecks in the operation of Ukraine’s harbors. First among these is the regulation of the ports, which the Ministry of Infrastructure is actively working to transform. A number of measures have been taken to deregulate ports, the number of procedures and oversight agencies has been reduced, electronic document use has been instituted and radio control automated, and mandatory control of insulated ballast has been dropped. All these steps are making it easier and cheaper for cargo to ship through Ukrainian ports and increasing their competitiveness at the international level.

RELATED ARTICLE: The prospects of Ukraine's agricultural sector

Another problem is the inadequacy of port infrastructure to the requirements of the times: most older infrastructure is depreciated by 75-80% and many parameters, such as the depth of the port channels, the number of docks, the number and quality of warehouses, roadway approaches, are suitable neither to the economy today nor to potential transit volumes. The Infrastructure Ministry, PAU and private companies are working on resolving this through local investment projects. The first efforts to systematize this kind of work were the previously mentioned strategic plans. However, since the Euromaidan, when private stevedoring felt the maximum of support from the state to attract investments, the quantity and quality of such investment projects that have been completed has skyrocketed, while the original plans have been adjusted substantially. That portion financed by the PAU has been growing steadily as well, thanks to the growing profitability of the company. In 2015, the Authority’s net profits were around UAH 3bnm, as opposed to UAH 647mn in 2013. The company receives its payments in hard currency but pays its expenses in hryvnia.

Consequently, plans in 2016 were for capital investment of UAH 3.5bn, five times more than in 2015. This money will go to such projects as building docks, reloading complexes, slipways for ships, and marine entry channels, freconstructing existing channels, including deepening this channel at Yuzhniy to 21 meters, and acquiring ships, cars, computer equipment and so on. Investments of one size or another are going to go into nearly every single port.

Dozens more investment projects are being financed by private companies. For instance, the strategic development plan for the port city of Chornomorske through 2018 approved in August 2015 includes 26 projects, mostly to develop reloading, warehousing and processing complexes, which will all be financed by private investors. Plans to develop the Odesa port include 12 points, only three of which will be financed by PAU and the rest by private independent investments, either solely or jointly with PAU.

The third problem is the actual sea ports are just one part of all the transport infrastructure in Ukraine whose state is far from what it should be. Roadways and railways need to develop in unison with the ports. This is extremely necessary if Ukraine wants to actualize its nationwide transit potential. In this instance, only the state, as the regulator and organizer of capital investment flows is in a position to do anything.

Promising strategies

Today, it’s clear that the process of developing the nation’s sea ports is underway and is picking up pace. This is being helped not only by changes in regulating and managing the sector, which has made it possible to attract private stevedoring companies and significant investments in improving port infrastructure. Another positive change was the considerable profitability of state enterprises: not only PAU has seen its profitability rise as a consequence of hryvnia devaluation, but the state ports themselves have too. For instance, in the nine months of 2015, Yuzhniy received UAH 796mn in net profits, whereas for all of 2013 it had only UAH 164mn.

Still, even all the good financial indicators, state ports are less mobile within the market and are realistically losing the competition to private stevedoring companies as their share of cargo handled shrinks. This process will continue, which means the profitability of state harbors is expected to go down. This means that Ukraine will gradually lose the value of these assets, but will gain greater quality of port services in exchange, better overall competitiveness of its ports, and growing volumes of transporting in the future.

RELATED ARTICLE: Ukraine's economic outlook in 2017

This exchange will benefit the country, but not necessarily the state. And so there are a lot of complaints these days about state ports being squeezed out of the market. Given the current situation, it is the best time to privatize them all. Realizing this, the Infrastructure Ministry submitted a bill to the Verkhovna Rada in August in which it proposes removing the state ports from the list of assets that may not be privatized. If passed, they could become the prizes of next year’s privatizations.

Still, in the long run, a number of more complicated issues also need to be resolved. Experts say that these investment projects could still be too little to bring Ukraine’s transit potential to the necessary level. The country needs to think about how to radically increase port territory. And this means that adjacent farmland will have to be rezoned and effectively sold to the ports. That is a serious issue that has not been resolved, due to the continuing moratorium on the sale of agricultural land in Ukraine.

With the signing of the Association Agreement with the EU, Ukraine could become the sea trade entryway into Europe for many countries in Asia. This was already noticed by China which signed a memorandum on building deep-water ports in Crimea with a throughput capacity of 140mn t of cargo per year. Those plans never materialized, but they have not been removed from the agenda. Inquiries from the Central Kingdom indicate that Ukraine needs to think of increasing the capacities of its ports and other transport infrastructure severalfold. Establishing branches of the Silk Road through the Black and Caspian Seas to bypass Russia confirm this once again. Ukraine needs to take advantage of this opportunity.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook

[1] Twenty-foot equivalent units measure the capacity of a container ship.