Ukraine is facing its next, eighth, round of Verkhovna Rada elections. In its relatively brief modern history, the country’s legislature has seen its role wax and wane, depending on the political situation, but there has never been a point where it had no power and functioned in a rubber-stamping capacity. On the contrary, over time its influence has essentially continued to grow.

1994: The great mix-up

The first VR elections in independent Ukraine took place on March 27, 1994. This snap election was called when both President Leonid Kravchuk and the legislature agreed to reboot the government: there had been a massive miners’ strike in 1993 that led to a political crisis. The VR election was then scheduled for the spring of 1994 and the presidential one for the summer.

The 1994 campaign was organized in a manner typical of the era and was marked by the kind of sloppiness and confusion that was common in the mid 1990s. The decision was made to elect deputies on a first-past-the-post (FPTP) basis with 450 “majoritarian” ridings, as they are called in Ukraine. Voting was to take place in no more than two rounds: if no candidate picked up at least 50% +1 in the first round, then the top two vote-getters would run off against each other in a second round. But even then, the winner was declared only if that person managed to get at least 50% +1 of the votes cast. Because voters were given a third option, “None of the above,” this requirement was not easy to meet in some ridings. Moreover, no winner was declared if less than 50% of voters turned up to vote in a particular district. In that case, a third round was officially called.

These difficult rules made it impossible for the 1994 election to result in a complete Rada. In the first round, only 49 candidates won outright, while 401 ridings underwent a second round. But even there, 114 ridings failed to declare a winner—and many of the third rounds also did not manage to come up with clear winners. The process was protracted and by early 1995, with 45 vacant seats, the Rada was still only 90% full. In the end, some districts did not have a sitting MP until the following election.

The result of this idiosyncratic election in 1994 was a very mixed-bag legislature. A total of 15 political parties gained seats and the majority of deputies were independents.

RELATED ARTICLE: Election Rules

1998: The Red comeback and its henchmen (and women)

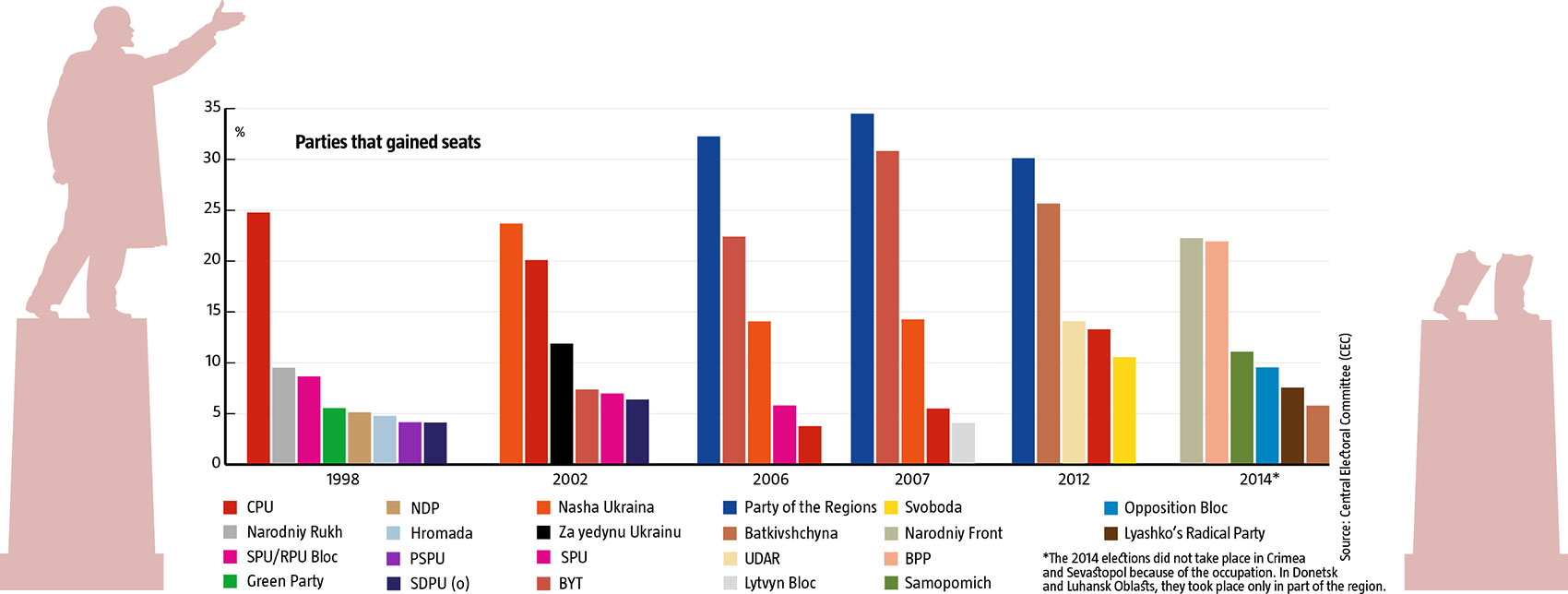

The 1998 VR election was the first “proper” election in the sense that Ukrainians know today. Voting, as now, was based on a mixed FPTP and proportional system: half of the deputies were elected based on party lists and half in “majoritarian” ridings. To gain seats in the Rada, parties had to reach a 4% threshold and eight parties met this requirement.

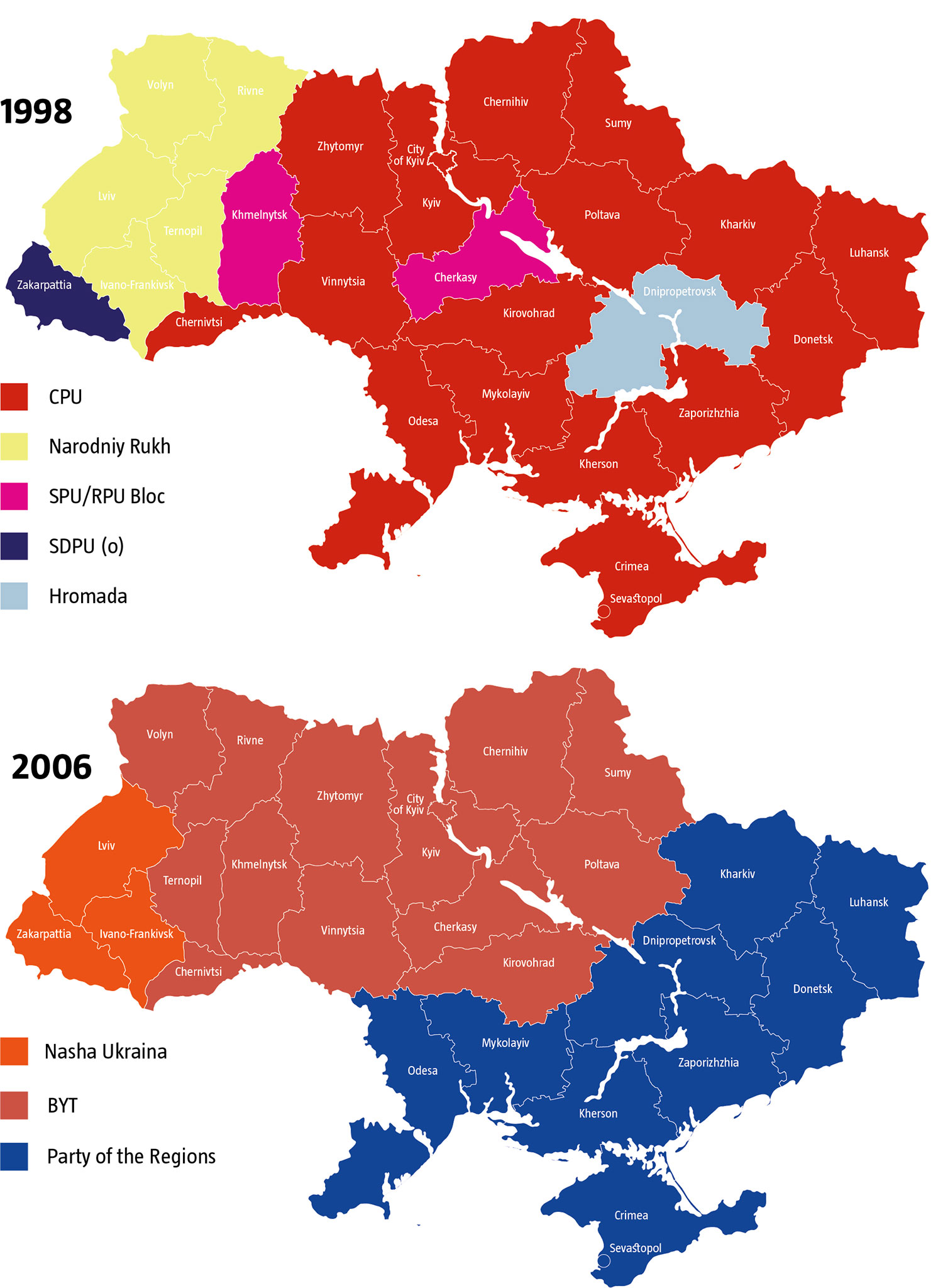

The results of this election from two decades ago would look like an utter disaster for contemporary Ukrainians, as it was a triumph of soviet comeback parties that looked to Russia. The top winner, with a big lead, was the Communist Party of Ukraine (CPU), which took a majority of seats in 15 oblasts, Crimea, Kyiv, and Sevastopol. Today, such an outcome can only be the stuff of nightmares, but 20 years ago, after several years of hyperinflation, and mounting unpaid wages and pensions, this was the reality in Ukraine. The communists came first even in western Chernivtsi Oblast. In two more oblasts, the Rural Party of Ukraine (RPU) and Socialist Party of Ukraine (SPU) won by appealing to the soviet electorate. The Progressive Socialist Party of Ukraine (PSPU) under Natalia Vitrenko, who was seen as a spoiler and little more than a clone of Oleksandr Moroz’s SPU, backed by then-President Leonid Kuchma, also gained seats in the Rada. However, the support “Vitriolic” Vitrenko had demonstrated the popularity of the radical red and brown slogans she espoused. What’s more, PSPU’s main stronghold was not the Donbas or Crimea but Sumy Oblast, where the party got 21% of the vote.

All told, the Reds got 37% of the vote and 174 seats, a similar proportion, in the Verkhovna Rada. Had that election been held on a proportional basis, such a legislature could have led to the collapse of the Ukrainian state, but the single-riding deputies saved the day because independents won in most of these districts and they tended to cooperate with the government. Moreover, in two oblasts the parties that won were “feudal” parties who were able to gain significant support through the administrative leverage provided by their invisible “masters.” For instance, in Zakarpattia Oblast, Viktor Medvedchuk’s SDPU (o) won with a healthy margin, taking 31% of the vote compared to 4% nationally. In Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, 35.3% of the vote went to Pavlo Lazarenko’s Hromada, of the most influential Ukrainians at that time and Yulia Tymoshenko’s patron.

The real surprise in the 1998 election was the arrival of the Green Party in the Rada. At the end of the 1990s, most Ukrainians were too busy worrying about getting paid to worry about ecology, yet the Greens managed to pick up more than 5% of the popular vote. However, many of them seem to have voted for this party as a form of protest.

2002: Red parties fade and Orange is in

At the start of the new millennium, the mood began to shift among Ukrainians and the protest voters began to turn away from the communists. The beginning of the end for the CPU was Petro Symonenko’s failed bid for the presidency in 1999, when he openly gave in to Leonid Kuchma.

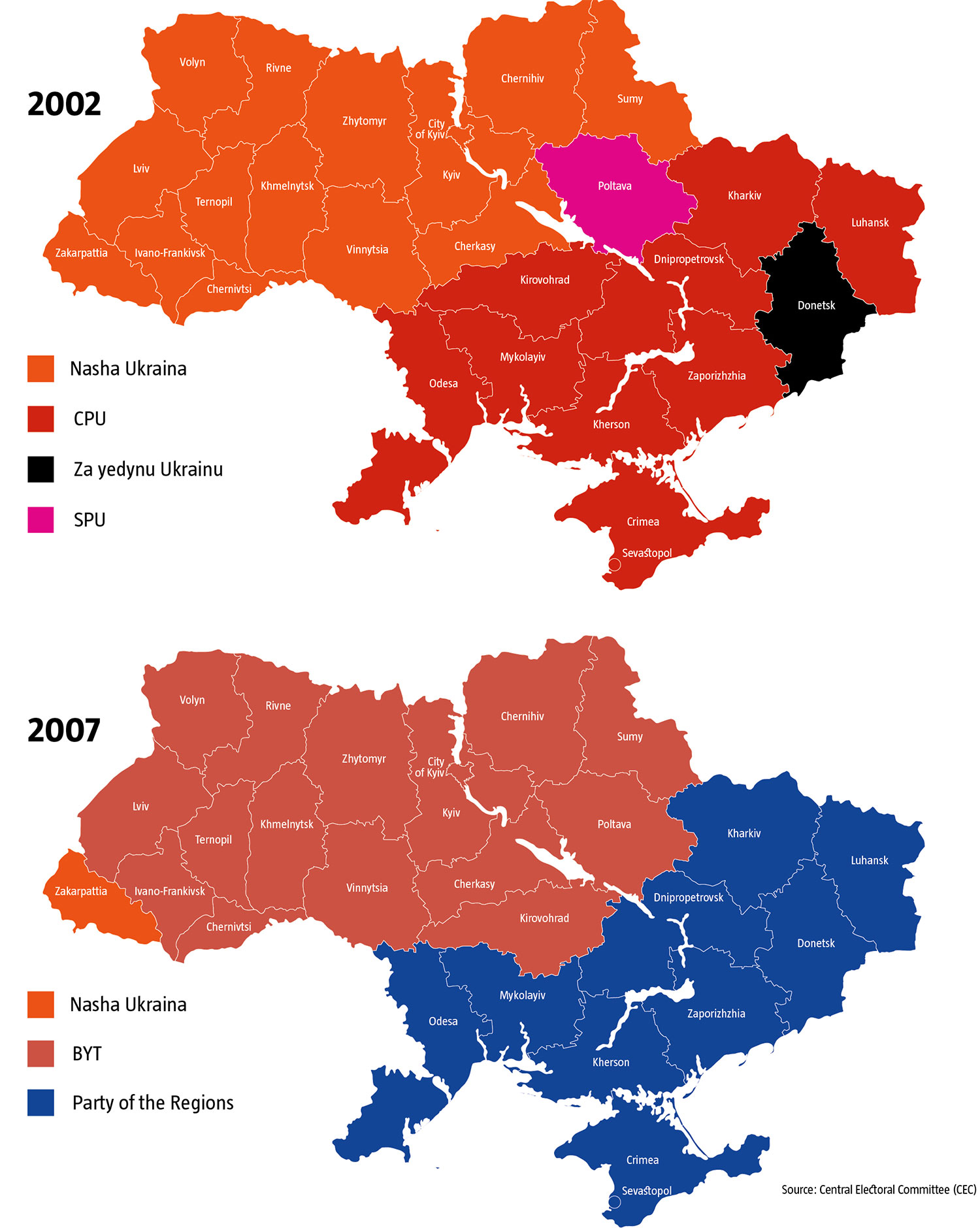

At the same time the national democrats managed to overcome the crisis that their camp faced after the death of Viacheslav Chornovil and a split in Narodniy Rukh. They also found a new, charismatic leader in Viktor Yushchenko, around whom a variety of minor parties began to unite. Eventually, these national-democratic forces took the name Nasha Ukraina, meaning Our Ukraine, and were associated with their orange-colored banner. In this election, the Orange camp had the highest share of the popular vote, 23.5%. NU beat out even the communists, whose popularity kept going down, as did support for the socialists.

In addition to Nasha Ukraina, the CPU and SPU, the pro-western Block of Yulia Tymoshenko (BYT) made it into the Rada, as did two pro-Kuchma parties: Za Yedynu Ukrainu and SDPU (o), Although they only had 18.5% altogether, the “independents” once again saved President Kuchma’s skin.

Kuchma’s “Za Yed U,” a pejorative nickname that read as “For Food,” got 11.8% of the vote, which translated into only 35 seats. But the eponymous faction in the Rada soon grew to 175 deputies, all thanks to “majoritarian” or independent deputies. In other words, the party that had far less popular support ended up the biggest force in the legislature. Za Yedu later transformed into the infamous Party of the Regions and was inherited by Viktor Yanukovych.

2006: A parliamentary republic

The 2006 Rada election took place in a very different country, where the Constitution had been amended to turn it into a parliamentary-presidential republic. After the 2002 triumph, the Orange camp proved successful enough to ensure Viktor Yushchenko’s victory in the 2004 presidential election after the much-lauded Orange Revolution.

After a dirty campaign that included ballot-stuffing and other manipulations, Viktor Yanukovych lost and it seemed like his political career was over. But as the Orange suffered from irreconcilable differences and endless squabbles between the two principals, Yushchenko and his PM, Yulia Tymoshenko, and the national democrats’ inability to make good on key promises like “Bandits to jail,” voters were quickly disenchanted and demoralized. Their ignominious defeat in 2004 consolidated the elites in southeastern Ukraine, who all looked to Russia. Yanukovych himself quickly recovered from the shock and mended fences with Yushchenko.

All these developments led to a sweeping victory for Party of the Regions in the 2006 VR election, taking over nearly the entire electorate of the CPU and becoming the main pro-Russian force in Ukraine. For the Communist Party of Ukraine, 2006 was a nightmare: the 20% of the vote it had gained in 2002 collapsed to 3.6%. The Party only gained a seat in the Rada because the threshold had been dropped to 3%.

In 2006, voting took place for the first time on a strictly proportional basis, meaning only according to party lists. This approach put an end to the free-for-all in the Rada. This time, only five parties met the threshold and they were clearly split into Orange and pro-Russian. The exception was Oleksandr Moroz’s Socialist Party, which joined the Orange camp. It succeeded in burying the Fifth Convocation of the Verkhovna Rada, which turned out to be the shortest-lived in the history of Ukraine.

Initially, the socialists formed a coalition with Nasha Ukraina and the Tymoshenko’s bloc, but then they suddenly switched to the other side and formed a coalition with PR and CPU. Even this formation failed to last long. President Yushchenko soon dismissed the legislature and called a snap election. Moroz’s betrayal proved to be the SPU’s swan song: they never made it into the next Rada.

2007: Another comeback

The 2007 snap election did not end up significantly changing the balance of political forces in the Verkhovna Rada. Once again, five parties gained seats, with the socialists replaced by the amorphous Block of Volodymyr Lytvyn, a former speaker. Its success was the big surprise this time.

Like the year before, Party of the Regions gained the most seats. BYT improved its position considerably, gaining 8.4% over its 2006 result to nearly match PR. In fact, Tymoshenko was the big winner this time. In December 2007, she took on the post of PM once again.

The results of this vote looked like a success for he Orange camp and allowed them to regain control of the Rada after the betrayal of the socialists. However, this success also proved short-lived when Viktor Yanukovych won the 2010 presidential election barely 2 years later. Within days, the legislature turned from orange to blue and white. This time the main role in the swift change of the guard was played by Lytvyn.

2012: On the path to dictatorship

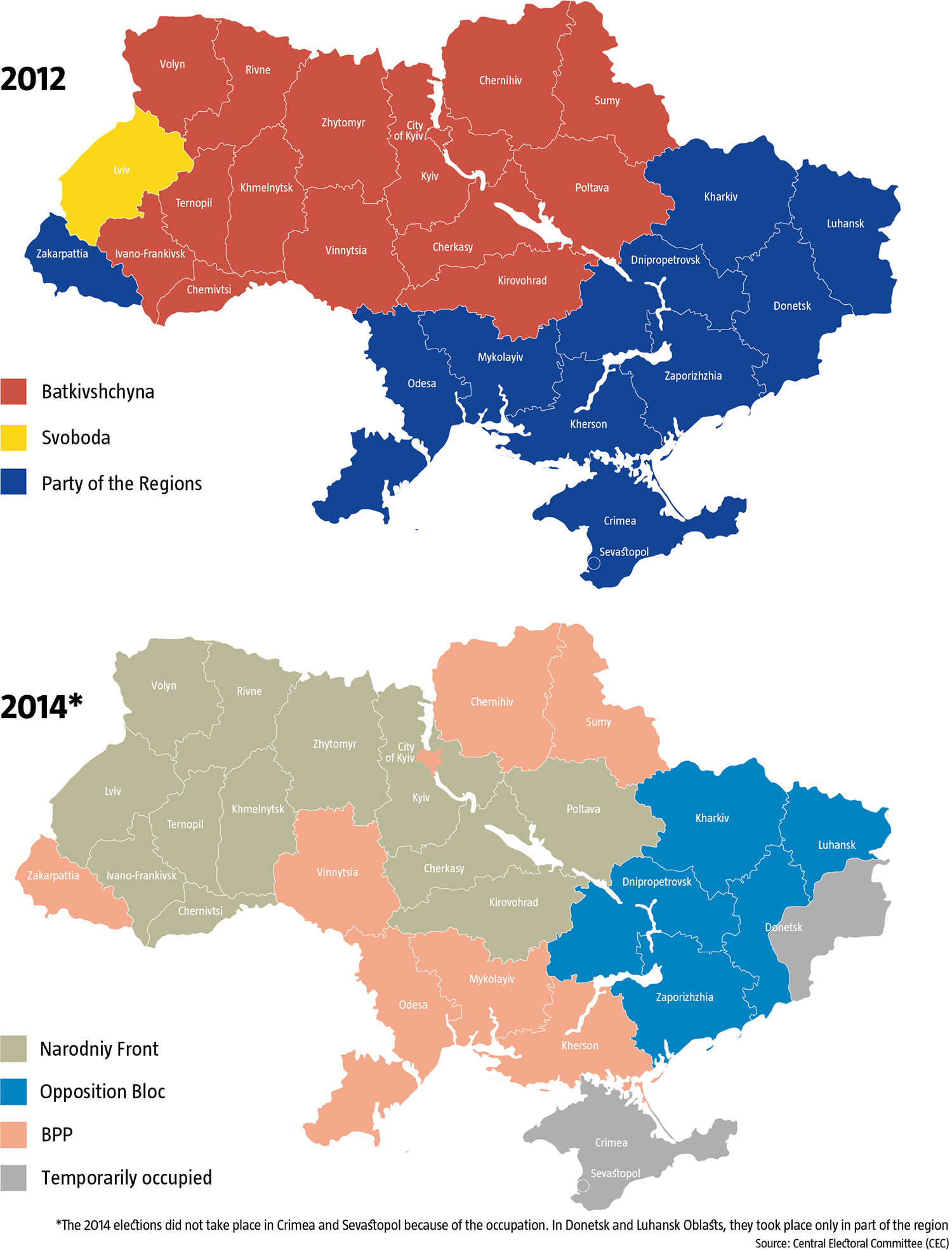

In 2012, the VR election went back to the mixed system. The new president understood by then that he would not be able to control the Rada as long as elections were proportional, and so he reverted to some of Kuchma’s old tricks: bringing a mass of FPTP deputies to the legislature who then helped him form a solid coalition to work on his agenda.

In the end, PR and CPU gained fewer votes than the opposition parties. Protest votes went to Svoboda, which surprisingly gained 10%. Even money and serious administrative leverage did not guarantee PR and its allies an unmitigated victory, but the “majoritarians” came to the rescue. Most of these supposedly independent deputies rapidly joined the pro-administration parties. Now Yanukovych had a legislature that he was in full control of. This helped him to strengthen his position in a short time, but in the end it could not save him from a disgraceful fall.

2014: A new era

After the Euromaidan revolution and Yanukovych’s flight from Ukraine, the issue of rebooting the government naturally came up. Once the president was replaced, it was time to replace the Rada as well. The occupation of Crimea and part of Donbas, armed conflict in the country’s east, and the collapse of Party of the Regions meant that any pro-Russian forces had no chance of taking power. And so, the 2014 election brought Ukraine its first Ukrainian legislature since independence. The rump PR, which campaigned under a new brand as the Opposition Bloc, was able to get only 27 deputies elected according to party lists. This was a real takedown. The rest of the Rada seats went to national-democratic parties that made use of harshly anti-Russian rhetoric and promoted European integration in their campaigns.

The new administration decided to leave the FPTP half of the election in place, which helped many former PR members to gain seats again and, as in the past, the “independents” tended to cooperate with them. They formed several factions in the Rada, but, in good political tradition, they began to play the ruling coalition.

The dramatic events of 2014, which was the most difficult year Ukraine had lived through, led to a major reshaping of the country’s political landscape. Old parties and politicians lost support and new heroes took their place. In spring 2014, Oleh Liashko’s star began to rise, when earlier no one took him seriously. He actively promoted himself in relation to the conflict in Donetsk Oblast and initially used in national-patriotic slogans. This, of course, pushed his ratings up quickly and he was able to get his party elected. The real “black swan” event in 2014, however, was the success of a completely new party, Samopomich or Self-Reliance, which had been formed not long before the election. Narodniy Front also showed unexpectedly high results, beating out even the Bloc of Petro Poroshenko, which had been expected to come in first.

2019: Coming soon…

What the 2019 election will look like is anyone’s guess. The only thing that can be said with certainty is that this will be the most unpredictable election. Party ratings are scraping the bottom like never before and political forces are fragmented. This means that any new alliance could radically change the balance of forces on the political front. Whichever candidate wins the presidency is certain to be successful in the Rada election as well, thanks to the usual undeclared mass of “majoritarians.” In the end, the mixed system was not changed, which means that the legislature will once again have dozens of deputies whose political positions are vague and who will be prepared to join whatever force promises the best terms.

RELATED ARTICLE: The chaos begins

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook