Angola is not England,

Russia is not Rus*

* A slogan on a poster the Russian police confiscated from Ukrainian football fans

Skeptical statements concerning Ukraine’s European integration have become a ritual these days. Over the past year, the West has been chilling down towards Ukraine, while the new government has been making some clearly anti-European moves. However, the fact that the West has no efficient policy regarding Ukraine does not result from the country’s internal weakness or a fatal coincidence of geopolitical factors alone. It is largely caused by a certain vision of Ukraine in the West based on several myths. They shape the image of Ukraine in the eyes of both the political elite, and common Europeans. In other words, the West has its own mental map of Europe where Ukraine is marked with a color identical to that of the neighbouring Russia.

Myth one

Ukraine and Russia: a thousand years in common

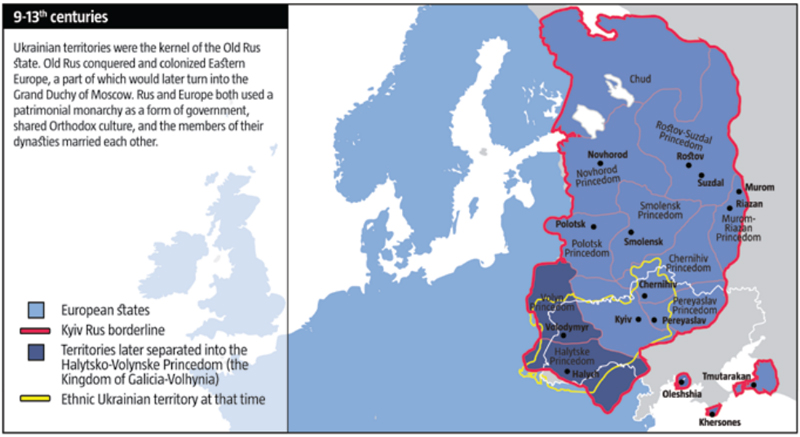

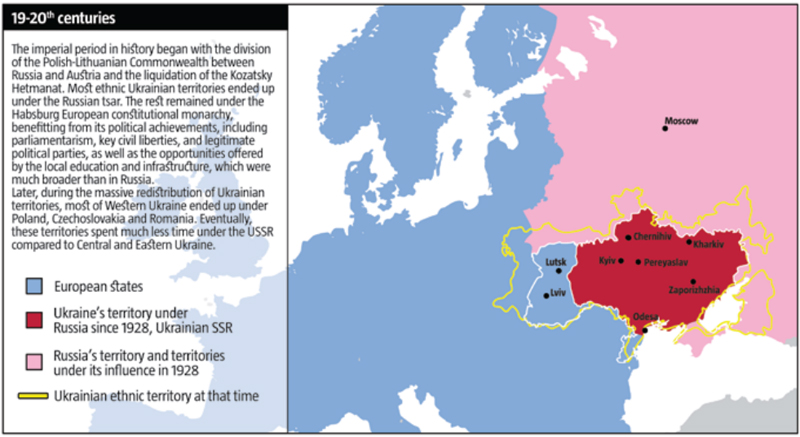

The most simple and general summary of Ukraine and Russia’s common past is that they were both integral parts of Kyiv Rus right from the early days of the Slavic statehood. As a result, Rus is thought to be Russia’s initial name, while Ukraine is considered one of Rus’ (read Russian) regions, such as Siberia or Povolzhie, the territory around the Volga river. The myth grew into a complete image offered to the West back in the early 19th century when Russian historians “privatized” the Old Rus state to please imperial ideologists, turning it into the foremother of the Muscovy and imperial Russian statehood. The national Ukrainian liberation movement, which had been accurately using the name Rus earlier to define old Ukrainian history, faced the need to find a different name from the one imposed by the Russian-centric propaganda. Thus, Ukrainian nationalists chose Ukraine, though in fact Rus had been the medieval name for old Ukrainian territories used by both Ukrainians and their neighbours. Also, this had been the name used on all European maps, and one of the Ukrainian provinces of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had been called Ruske. After all, Ivan Vyhovsky[1] wanted to turn the Kozak Hetman State into the Grand Rus Princedom in mid 17th century. Ukrainian territories had been the center of the Old Rus state which had covered the Eastern part of Europe. A great part of these territories had always belonged to the European civilization in terms of culture and politics.

The West sees the Holy Rus as the umbilical cord which had strongly tied Ukraine and Russia together with common culture, language, state structure and, of course, Orthodoxy. The image of the inseparable Rus and Russia is also promoted at various art events, such as exhibitions and conferences on Old Rus art, which focus on the Russian historical background. Also, most Western research centers and university departments have Russian and soviet history and culture studies which dominate over all others. To please soviet imperialism, these myths were accomplished with the images of Rus as a “cradle of brother nations,” the Orthodox Slavic world with all its values cut off from Western ones.

This myth seems the most resilient and consistent of all because this commonness of Ukrainian and Russian civilization roots is used to explain the current stage of development of both countries and their relations with each other, including inevitable integration and co-existence, and their attitudes towards the West. Who cares if the Byzantine heritage absorbed by both Rus and Muscovy developed in completely different ways in these two cultures?: In Muscovy it was an Orthodox dogma segregating it from the rest of the world with an iron curtain; in Rus-Ukraine, it only served as a platform which was later freely influenced and changed by various Latin trends. The West prefers to see this common Byzantine heritage only as the foundation of the uniform undividable Old Russia, not Old Rus. Even the arguably “common” Orthodoxy looked totally different in both countries in post-Old Rus times. The dynamic Kyiv Orthodoxy, which was more flexible and coherent with Western Orthodox influences, still preserved its uniqueness in contrast to the ill-educated, conservative and xenophobic Muscovy Orthodoxy, which was filled with arrogance and a sense of superiority. The ruling elite and their political culture also developed in opposite directions: the progress of Rus’ political culture was based on the rule of law and dominating regional diversities, while the process in Muscovy was autocratic, granting minimum liberties and rights.

Myth two

The victory of democracy in Ukraine will overcome authoritarianism in Russia

This myth is a dream of Russian dissidents who used to see the victory of democracy in Ukraine as a triumph of civil liberties in one of the largest republics of the European part of USSR which should have led to a collapse of the Communist system, rather than from a perspective of their national interests. The current Russian opposition follows this belief as psychological anesthesia of sorts, not a principle. It sees Ukraine as virtually the only arena in the whole FSU which they can still use to manifest their slogans, ideas and intentions.

The dreams about democracy in Ukraine have captured the Western political establishment and society so much that even the very first participants of the Eastern Partnership programme, designed in mid 2000s, placed a stake on Ukraine as a pilot role model of structural progress in the entire “younger Europe,” and clearly hinted at their expectations that the political climate would soften in Russia, too. These expectations of the West always fed on their belief that political processes were closely tied in Ukraine and Russia. This, in turn, is coherent with the previous myth about the common roots of their political culture and statehood.

However, the West will face huge disappointment no matter if real democratic values win or fail in Ukraine. A triumph of freedom and democracy in Ukraine can only serve as one of the prerequisites for a change of the political model in Russia today, making its democratic transformations less painful. But the miracle will not happen because the West knows very well that in a huge and ill-integrated country like Russia it is hard to project the direction of socio-political changes which are affected by deep corruption, suppressed chauvinism and a shaky economy. Therefore, democracy and the building of an efficient state in Ukraine should be viewed not as an instrument, but a self-sufficient goal in itself which will secure the West from radical changes in the course of the atomic icebreaker called Russia.

myth three

Ukraine safe from violent scenarios

This myth is yet another example of wishful thinking. The assumed easygoing nature of Ukrainians and its people is seen as a demonstration of the fact that Ukrainian society and government are weak, amorphous and spineless – a peaceful and non-aggressive Little Russian psychological type. The past 20 years of its sovereignty and independence seem to prove this. A long-lasting indecisiveness as to the building of a statehood and the shortsighted elite brought to life a concept of multi-vector foreign policy in mid 90s, which with time, turned into a funny game of running with the hare and hunting with hounds – depending on the circumstances the given political regime was facing. The few territorial conflicts with Ukraine’s neighbours over Tuzla and Zmiyinyi islands were local and never grew into anything big. Domestic opposition has always been soft without any extremism or blood shedding. Even the Orange Revolution of 2004 was a peaceful event accompanied by tuneful concerts.

However, this sanguine concept leaves out many factors which are potentially risky. They do not include conspiracy scenarios among political extremists inside the country which the current government has recently been speculating on to scare everybody. Ukraine could turn into a hot spot in Europe only if a slew of factors blend together. The most serious one is a combination of integration scenarios Russia could use when it is no longer happy with the current pace and nature of the merger of economic systems and the grabbing of markets and resources, then it might have a go at political acquisition, which could result in violence. This was what happened in summer 2008, when Ukraine could have been dragged into the military conflict between Russia and Georgia in just a matter of days.

Another factor which will probably add to foreign policy troubles is the mood within the Ukrainian society, which is growing more radical as people become more discontent with the declining quality of life, inefficient and corrupt government, and no positive social prospects. It looks like this factor can be decisive, yet the most unpredictable, in the unfolding of a massive and long-lasting conflict in Ukraine. Western analysts mostly ignore the fact that one of the most important elements of Ukraine’s social development is a viable middle class which would protect the values of freedom, individualism and economic independence. The middle class has always acted as a catalyst of resistance to any attempts at foreign control over its life and the life of Ukraine, from the early modern era of kozaks through to the recent times of the middle class peasants and their uprisings in Naddniprianshchyna[2] in 1917-1923 or the UPA, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. Therefore, virtually all authoritarian regimes wanted to eliminate it and clear the space for their domination. Yet, the resistance hardly faded even at the hardest times under totalitarian regimes. After the dreadful famine in 1932–1933, Ukrainian peasants paid the government back with massive desertion in 1941, the early years of WWII.

Dispelling myths is not just intellectual entertainment, especially when they serve as drivers of politicians’ actions. Obviously, the West will only start revising its twisted vision of Ukraine when it feels the real threat of its shortsightedness. The success of this enlightenment largely depends on how Ukrainian intellectuals and the public work on it.

Eternal Russia

Ilya Glazunov created this monumental painting in 1988, during the time of Khrushchev’s Thaw and no censorship. This allowed him to bring together significant figures from pre-Revolutionary and soviet eras. The painting perfectly reflects Russia’s vision of itself and Ukraine imposed on the West.

Historical heroes of Old Rus and Early Modern Ukraine, from Apostle Andrew to Saints Borys and Hlib, Volodymyr the Great, and Bohdan Khmelnytsky, found themselves in the front rows of the “eternal Russians.”

There is one interesting fact: in 2009, Russian Prime-Minister Vladimir Putin visited Glazunov’s workshop on the artist’s 79th birthday. Looking at the Eternal Russia painting, Putin noted that Borys and Hlib were, of course, saints, but “you have to fight for yourself, for your country, and they gave everything away without any struggle. We cannot follow their suit; i.e. sit and wait until somebody kills you,” he shared.

[1]Ivan Vyhovsky was the pro-Polish hetman of Ukrainian Kozaks in 1657-59 during the Russian-Polish War.

[2]Dnipro Ukraine, otherwise known as Great Ukraine, was the territory of Ukraine in the Russian Empire, not including Halychyna (Galicia) in the west and the Crimea.

The Real History of Ukraine

A common millennium history with Russia is a myth. Ukraine spent most of its time as an independent country or part of European states