While Ukraine is discussing how real or imaginary the victory in the Stockholm arbitration court of Naftogaz vs Gazprom is, one question becomes more and more relevant: what will happen in 2020 when the transportation of Russian gas through the Ukrainian gas transit system (GTS) is stopped or reduced to a minimum? The existing transit contracts, the subject of the ongoing dispute between Ukraine’s Naftogaz and Russia’s Gazprom in Stockholm, end in 2019. Which is not too far from now. Meanwhile, Gazprom CEO Alexey Miller said in an interview with Reuters on April 25, 2017 that his company does not rule out maintaining certain transit volumes through Ukraine after 2019, but they will be limited to a level of around 15 billion m³. The current amount is 80-85 billion m³. The remaining deliveries will be exclusively for the needs of countries bordering with Ukraine. The chances of these plans succeeding are very high. Despite numerous obstacles, the systematic and persistent work of Russian lobbyists to push alternative energy supply projects in EU countries yields results. While it may be possible to put the brakes on Gazprom's intentions for a few years, stopping them completely is unlikely.

Therefore, Ukraine should focus primarily on asymmetric countermeasures. So that when Russia finally makes its plans reality and has the technical ability to transit the bulk of or all current gas to the EU bypassing Ukraine’s GTS, we will be ready and able to minimise potential threats. At least two are looming. Firstly, it will become more complicated to purchase gas from European suppliers and the price will increase significantly. Unless action is not taken, Ukraine will have to transport the fuel from distant European hubs following the termination or minimisation of gas transit through its GTS instead of buying Russian gas on Ukraine's western borders after its transfer to European companies, as is the case now. Secondly, transit revenues will be lost and it will be more expensive to transport fuel for domestic consumers using the Ukrainian GTS, as they will have to pay most or all of its operation costs. As a result, industrial production may become even less competitive compared to other countries in the region, in addition to higher gas cost for domestic consumers.

Slowly but surely

Despite the scepticism and resistance to the Nord Stream pipeline, which runs under the Baltic Sea directly from Russia to Germany with a capacity of 55 billion m³, it was finally built in 2011. Albeit with significant delays (contrary to initial expectations), it is now working at almost full capacity. Slowly but surely, Gazprom is pushing for Nord Stream-2 and a number of pipelines in the EU that would ensure the supply of natural gas from the two Nord Streams to various European countries. In order to bypass the obstacles presented by EU regulators, Nord Stream 2 AG and European energy companies ENGIE, OMV, Royal Dutch Shell, Uniper and Wintershall signed a financing agreement on April 24, 2017: these five companies have committed to providing long-term funding amounting to 50% of the total project cost (estimated at €9.5 billion), while Gazprom will remain the sole shareholder of Nord Stream 2 AG. It is planned that pipeline construction will begin in 2018 and be completed by the end of 2019.

RELATED ARTICLE: The very costly secret: The pitfalls of Yanukovych's $1.5bn case

Despite the failure of South Stream, which was designed to cross the Black Sea from Russia to Bulgaria and further into the EU in order to deprive Ukraine of Russian gas transit to the Balkans and Italy, Moscow was able to come to an agreement with Turkey. Regardless of the aggravation of Russian–Turkish relations in 2015 due to Syria and the Russian aircraft shot down by the Turkish Air Force, Ankara issued the first building permits for a comparable pipeline, the Turkish Stream, in September 2016. Its bilateral implementation agreement came into force in February 2017, while the company South Stream Transport B.V., originally established for the construction of South Stream, concluded a contract with Allseas Group for the construction of a second line. By early May, work had already begun on the underwater part of the pipeline. Currently, this means there will be two lines with a capacity of 15.75 billion m³ each, one completely dedicated to further transit through the European part of Turkey to the EU (the Balkans and Italy).

Actual construction of the underwater part of Turkish Stream started in May 2017. Alexey Miller has stated that that "the project is being delivered strictly according to plan and by the end of 2019 our Turkish and European consumers will have a reliable new route for importing Russian gas". This is a very realistic timeframe given previous pipeline experiences. Blue Stream, the first pipeline in the Black Sea from Russia to Turkey designed to bypass Ukraine, through which all Russian gas has been transported to this country until now, was built fifteen years ago. Construction of its offshore section with a capacity of 16 billion m³ lasted less than a year – from September 2001 to May 2002. Commercial supplies started another six months later in February 2003.

Early preparations

However, there is more to it than the construction of the main pipelines. Gazprom is actively working towards creating pipeline infrastructure to distribute their fuel to as many consumers as possible who now receive it in transit through Ukraine, particularly in Central Europe. Gazprom booked new capacity at auction in March for extra supplies that are supposed to come through Nord Stream 2 to Germany (58 billion m³ per year at the point of entry), the Czech Republic (around 45 billion m³) and Slovakia for the period from October 1, 2019 to 2039. To this end, preparations are being made for the construction of other transport networks: the EUGAL pipeline to move additional amounts of gas from the north of Germany to the south and the Czech border (planned capacity of up to 51 billion m³ per year) and the expansion of gas transmission systems in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. In April 2017, Wintershall board member Thilo Wieland said that the construction of EUGAL will start in mid-2018 and that gas will start to flow through its first branch by the end of 2019: orders for building materials have already been made and the tender for the works is proceeding at "full speed".

The existing OPAL pipeline with a capacity of 36 billion m³ that connects the first Nord Stream to Germany and the Czech Republic (EUGAL is supposed to run parallel to it) has already demonstrated how threatening such projects are for the Ukrainian GTS. They open access that bypasses Ukraine to key EU markets for our transit. At the end of October 2016, when the European Commission relaxed restrictions and for a short time approved an increase from 50% to 80% in the capacity that Gazprom could fill with Russian gas from Nord Stream, it caused an immediate and sharp decline in fuel transportation through Ukraine's GTS. In December, Naftogaz was forced to sound the alarm, because the use of the Nord Stream–OPAL route increased from 57.1 million m³ to 80.5 million m³ per day, while the volume of gas transportation through the Ukrainian GTS towards Slovakia decreased from 148.9 million m³ to 120.8 million m³. The European Commission's approval was later overturned in court. However, the planned construction of EUGAL with "spare" capacity can take away the lion's share of Ukraine's transit, even if Gazprom only fills it to the 50% allowed by European legislation.

RELATED ARTICLE: The dynamics of Ukraine's trade with Russia, key sectors of commercial interaction

The situation is similar in the South. If completed, Turkish Stream will enter Turkey in its extreme western, European part, the location of a section of the Trans-Balkan Pipeline that until now transported Russian gas transited through Ukraine to Turkey and the Balkans. In this way, Gazprom could easily transfer its supplies not only to Turkey (11.6 billion m³ in 2016), but also to Greece and Bulgaria away from the Ukrainian GTS. Combined, this is about another 6 billion m³. Furthermore, Gazprom signed a cooperation agreement with European companies Edison and DEPA on June 2, 2017 that envisages the joint organisation of a southern route to supply Russian gas to Europe through Turkey, Greece and then Italy via the Poseidon pipeline. Elio Ruggeri, Vice-President for Gas Infrastructure at Edison, announced earlier this year that the likely project completion date will be before 2022.

In early 2017, Gazprom Deputy Chief Executive Alexander Medvedev said that the company is also willing to consider using the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) to supply Italy with Russian gas. Construction started in May 2016 and is currently 40% complete, due to be finished by 2019. TAP, which was originally planned for transporting natural gas from Azerbaijan and other countries in the Caspian Sea region and Middle East to Europe, was supported by the European Union for the purpose of diversifying fuel sources, but could now facilitate the implementation of Gazprom's plans. On the basis of the same EU energy legislation, the Russian monopolist can bid for 50% of TAP capacity (which is planned at 10 billion m³ with a potential expansion to 20 billion m³). Therefore, from 2020, when the Turkish Stream has a high chance of being completed and the current contract for the transit of Russian gas through the Ukrainian GTS comes to an end, much of the natural gas consumed by Italy could be transported through the TAP.

Changes in consumption

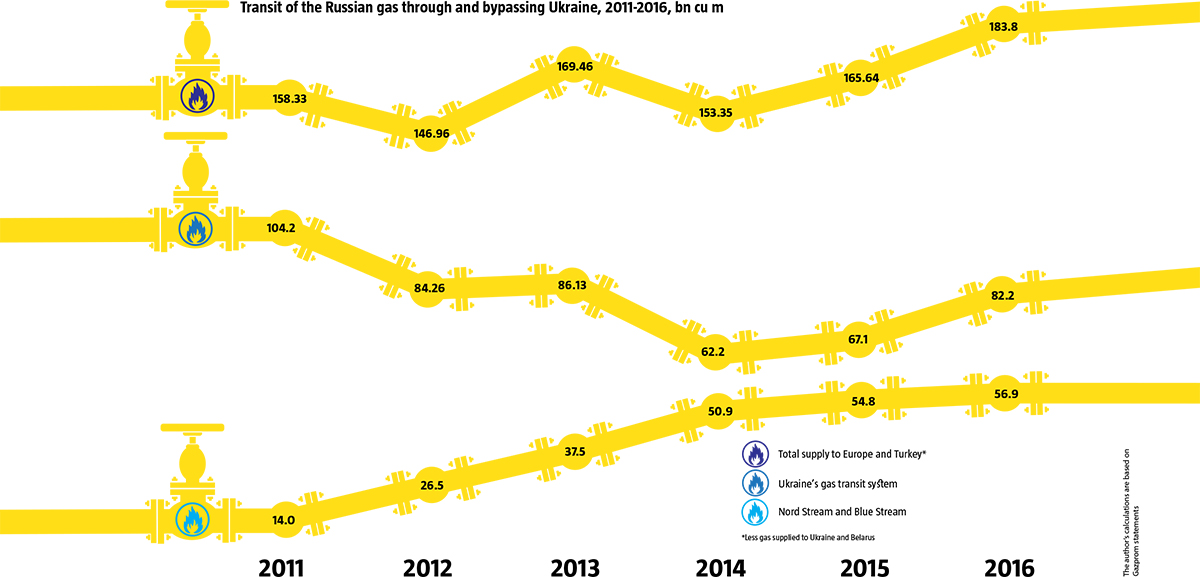

Russia's move away from gas transit through Ukraine after 2019 could be made easier by significant changes in the geographical spread of its exports over recent years. From 2011 to 2016, the importance of the following markets grew for Gazprom: Germany (from 34 billion m³ to 49.8 billion m³), Great Britain (8.2 to 17.9 billion m³), France (9.5 to 11.5 billion m³) and Austria (5.4 to 6.1 billion m³). It would be easier to increase exports to most of them through Nord Stream and Nord Stream-2. On the contrary, the share of consumers that received all (or most of) their Russian gas through Ukraine has decreased. For example, supplies to Central Europe (excluding Poland and the Baltic states) declined from 30.8 billion m³ (2011) to 23.9 billion m³ (2016). Even exports to Italy (24.7 billion m³), which now account for the largest proportion of Russian gas transit through the Ukrainian GTS, have been stagnating since 2013. The country has an active policy of balancing out Russian gas supplies with those from Algeria, which has recently increased deliveries.

The main factor that is clearing the way for Russia to enter the gas market of the industrial core of Europe (northwest Germany, the Benelux, north-eastern France and England) is the dramatic decline of gas production in what was until recently one of the largest European suppliers, the Netherlands (from 77.7 billion m³ in 2013 to 45.5 billion m³ in 2016). This decline was offset by increasing supplies from Russia and Norway (10 billion m³). In addition, natural gas is becoming more popular in these EU countries as an alternative to coal in thermal power generation. In 2016, the share of coal power generation in the UK dropped to 9% from 23% only a year earlier, mainly due to a newly introduced tax on emissions. There are plans to close the country's last coal power plant in 2025. Meanwhile, members of the Eurelectric electricity industry association from 26 countries have pledged not to launch any new coal power facilities after 2020.

Removing the need for imports

When Gazprom is able to transfer gas supplies to such large consumers as Germany, Austria, Czech Republic, France, Italy, Turkey and Greece onto other routes, it will be able to abandon the lion's share of transit through Ukraine by reducing its maximum level to the volumes required for Moldova, Slovakia, Hungary and Romania, which have collectively been buying from 13 to 14 billion m³ of Russian gas in recent years. This will clearly make it impossible to ensure reverse-flow supplies of almost the same amount of gas to Ukraine (11.1 billion m³ in 2016) which the country needs to purchase from its western border.

Therefore, the first strategy for responding to the threat that Gazprom will stop fuel transit to the EU via Ukraine should be the reduction – and ideally elimination – of the need to purchase it by the early 2020s. This objective can be achieved by both increasing domestic production and taking advantage of the significant potential to reduce the consumption. While the production in both the public UkrGasVydobuvannya and most private gas producing companies is increasing and could continue to grow, the government uses very little of the opportunities available for further reducing energy use.

According to Naftogaz, consumption of natural gas in 2016 declined by only 0.6 billion m³ compared to the previous year (though the State Statistics Bureau actually shows that it increased). The problem is structural, however: while industry has reduced consumption by 1.3 billion m³ (from 11.2 to 9.9 billion m³), household consumers and regional heating providers, whose consumption is most affected by energy conservation measures, on the contrary used 0.8 billion m³ more than in 2015 (19.2 from 18.4 billion m³). The industrial sector has virtually exhausted its space for savings. Despite the potential for energy savings at most facilities, energy use may even increase in the coming years if economic growth recovers.

RELATED ARTICLE: What's missing for the management of state enterprises in Ukraine to be properly reformed?

Therefore, without measures focused on reducing the excessive consumption of natural gas by local heating providers (which was clearly seen during the latest heating season) and other household consumers, gas use in Ukraine in the coming years could even increase. According to the State Statistics Bureau, in January–April 2017 Ukraine consumed 16 billion m³ of natural gas, or 11.6% more than in the same period in 2016 (14.35 billion m³). This occurred despite the significantly warmer spring and the suspension of the heating season in most parts of the country in early April. In annual terms, consumption reached 33.68 billion m³ (excluding what was used for transportation by Ukrtransgaz) from May 2016 to April 2017, compared to 30.29 billion m³ for the 12 months from September 2015 to August 2016 when the country recorded its lowest level of gas consumption since gaining independence.

The government must monetize subsidies to households as soon as possible, and step up the funding for energy efficiency. In the first quarter of 2017, according to the Ministry of Energy and Coal Mining, thermal power plants and combined heat and power plants (CHPPs) alone consumed 1.67 billion m³ of natural gas out of 12.83 billion m³ total use in the country (compared to 4 billion m³ for the whole of last year, a figure which in 2017 is even expected to increase). The main consumer in the first quarter of this year (0.813 billion m³) was KyivEnergo, controlled by Rinat Akhmetov's DTEK, which burns fuel extremely irrationally, alongside other CCHPs in the country's major cities: two in Kharkiv (214.8 million m³), Kryvyi Rih (76.1 million m³), Odesa, Kremenchuk, Darnytsia [district in Kyiv] and Lviv (40-60 million m³ each for a total of 202 million m³).

If Ukraine continues to burn gas to heat apartments in large cities, then with the current deterioration of heat distribution networks it is necessary to move towards maximum decentralisation, i.e. establishing boiler facilities near major customers. Given the heavy losses when transporting heat through an entire city, the centralised supply of hot water is also superfluous (at least outside the heating season). Even the supplying companies admit that individual apartment boilers would be more cost-effective. This will require urgent measures to increase the capacity of electrical installations in residential buildings, but would reduce gas consumption. At the same time, thanks to tariff incentives the increased use of electricity for heating water can be concentrated during periods of minimum daily consumption. This will also create the conditions for a more balanced energy network and the production of more cheap power at nuclear plants.

Transporting Russian gas without Gazprom

The end of gas transit through the Ukrainian GTS from 2020 is not only a threat, but also an opportunity for the transit potential of Ukraine. The confrontational model of relations with Gazprom that has been seen in recent years could hardly be considered optimal under normal circumstances. However, looking at the way the Russian company imposed its own terms of doing business before 2014, which was most evident in the onerous contracts of 2009, there is ultimately no alternative. Especially against the background of Russian aggression against Ukraine.

Therefore, the best option would be to completely reject any contracts with Gazprom after 2019 and make contracts only with the European companies that purchase gas from it. That gas would have to be handed over at the Russia–Ukraine or Belarus–Ukraine border.

Firstly, this will end the dependence on a gas transit monopolist, and replace it with 5-7 or possibly more European companies that will buy fuel from Gazprom at the Russian border. Secondly, there will be the opportunity to make better use of the Ukrainian underground gas storage (UGS) facilities that the Russian supplier has long ignored for political reasons. European companies could fill them with fuel purchased on the Russian border for periods of peak consumption, which is beneficial for them. Thirdly and finally, in this case Ukraine would not have to buy gas from European hubs at an inflated price. Even if a certain deficit in domestic production is maintained, Ukrainian consumers would be able to purchase fuel from European companies immediately after it enters the Ukrainian GTS from Russia.

If favourable conditions are created for European purchasing companies to transport Russian natural gas through the Ukrainian GTS and store it in UGS there, its transit through our territory could not only not decrease, but actually increase from the current volume, even after Gazprom completes its bypass routes. Though on a new, competitive basis. For this, it is necessary that the prospect of purchasing fuel on the Russian border be significantly more attractive for European companies than buying it after delivery to hubs in Turkey, Austria and Germany. Perhaps Kyiv will have to agree on joint ventures to run the Ukrainian GTS (or some of its main pipelines) with the European consumers of Russian gas for whom the Ukrainian supply route could be economically advantageous under certain conditions (Germany – 49.7 billion m³, Italy – 24.8 billion m³, France – 11.2 billion m³, Austria – 6.1 billion m³, Hungary – 5.5 billion m³, Czech Republic – 4.5 billion m³, Slovakia – 3.7 billion m³, Bulgaria – 3.2 billion m³, etc.).

It is important to create real economic incentives so that it will be profitable for European companies to demand that Gazprom sell them fuel at the Ukraine–Russia border and then transport it further within the framework of the European Energy Community until legislation is changed and certain main pipelines can be sold to joint ventures started with European companies. Ukraine, in turn, will be able to keep its GTS functioning without putting it under the management of Russia or going into a joint venture with it, on which Gazprom always insisted in exchange for continuing its transit through our territory.

RELATED ARTICLE: Changes in Ukraine's banking sector: consolidation, different owners

Of course, Ukraine will also depend on its Western partners (mainly Slovakia), as their rates for transporting fuel from Ukraine further west will influence whether potential customers give preference to the Ukrainian route or Gazprom's pipelines. However, our neighbours are no less interested in preserving the old transport route than we are, as otherwise they would also lose the lion's share of their transit.

Moreover, the termination of Russian gas transmission to the Balkans through the Ukrainian GTS could create conditions for the start of deliveries of Caspian natural gas from Turkey to Ukraine through the Trans-Balkan Pipeline. Working in the opposite direction, it could be a tool for diversifying hydrocarbon supplies to Ukraine and then – using our GTS – to other neighbouring countries in the region.

Only when we take up the active position of a party to the struggle for transit routes will we be able to interest key European companies in such a transport format and will we have a chance to retain the transit of Russian gas through our territory after 2019 and make our underground storage facilities available for constant commercial use in cooperation with other European companies. It is necessary to put guarantees in place so that some or all of the shares in the joint ventures launched with companies from Europe will not be transferred to Gazprom or another structure controlled by the Russians in the future.

Translated by Jonathan Reilly

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook