In 2019, five years after the Revolution of Dignity, reforms in the Ukrainian energy sector and all the remaining national matters related to it, seem very far from being complete. Goals, which were presented in the 2014 parliamentary collation agreement, were never reached. Thus the country is still rather far from its initial aim – improving energy self-sufficiency, securing the energy independence and reaching effectiveness of the energy sector, improving quality of the services, provided by the energy enterprises and brining this industry up to date. Failure of the gas sector reforms was the most evident. This issue became especially distressing bearing in mind the so-called ‘problem of 2020’, the year when current gas transit contracts with Russia will come to an end. Ukraine, however, is hardly prepared for an aftermath of such scenario.

Ukraine faces further problems with the planned transition into electricity market, which is due to commence on 1 July 2019. When it comes to the electricity market, the main issue is not the market itself, which in theory may easily become very competitive in supplying energy to consumers, but the problems of the deep economic monopolies and vulnerability of Ukraine’s energy sector. Recently, however, various energy experts and commentators have been focusing on the different ways to sell or the electricity as well as issues related to the electricity trade itself, rather than the problems related to the way this electricity is generated.

Gas failure

In spring 2016, when the former prime-minister of Ukraine, Arseniy Yatsenyuk, and his government, were replaced by team led by Volodymyr Groysman, it appeared that the solid reform of the gas sector is under way. Three years have passed and it now seems even further away. Three years ago Ukraine finally balanced the gas prices for different consumers on a level similar to the European market. Further, the government initiated a program which was aimed at increasing output of Ukraine’s own gas, hoping that these capabilities would fully satisfy Ukraine’s needs by 2020. Additionally, at that time the issue of reforming Naftogaz, Ukraine’s national oil and gas company, and its separation from the transit gas system seemed to be solvable by early 2019. Once the country’s gas sector was restructured this way, it would be effective and functioning even in the event of complete cut off of the Russian gas supplies, and ensuing complications of the reverse gas flow from the EU countries.

If successfully implemented, Ukrainian ‘2020 program’ would increase country’s own gas output by at least 27 billion m3, and would eliminate possible Gazprom’s threats to terminate its transit agreements with Ukraine and use the pipelines in Baltic and Black seas instead. Additionally, if Ukraine succeeded to effectively balance out its gas output and the subsequent consumption, this could lead to price decrease for local consumers. In this case the “European hubs plus transportation costs” formula would be replaced by “European hubs minus transportation costs”. Unfortunately, at the moment the program has proven to be an absolute failure.

RELATED ARTICLE: Guarding the сompetition

Ukrainian government showed a disappointing lack of political will when it comes to adhering to market price formation process and reform of Naftogaz. Local corrupt administrative authorities across Ukraine have remained the key obstruction to the planned reforms. These authorities repeatedly sabotaged discovery and development of the new wells. These disruptions were especially obvious in Poltava region. At the same time, no new legal mechanisms were implemented to stimulate businesses to balance out the levels of profits to the levels of output.

Furthermore, Ukrainian government has not undertaken any steps to encourage both the private consumers and the large businesses to reduce its gas consumption. State funds, allocated to the energy saving program were minimal and amounted to UAH several billion, while the state gas subsidies were worth UAH hundreds of billions. Additionally, government’s subsidy incentive itself was completely demotivating when it came to upgrading energy saving equipment in the buildings – because in addition to increased spending, the owner of the house would also get his subsidies cut. Thus an average consumer would not experience any financial relief as a result of adopting gas saving system in their home.

Ukraine is yet to explore a number of opportunities to decrease big enterprises’ gas consumption, which were not made use of before. For instance, several thermal power plants in Ukraine still consume huge amounts of gas, used a fuel – for instance it reached 3.9 billion m3 in 2018. Kyivteploenergo, Ukrainian enterprise supplying electricity and hot water to the capital, and Darnytsia thermal power plant, used 2.03 billion m3 in Kyiv, two thermal power plants in Kharkiv used 0.56 billion m3, several thermal power plants in Kremenchuk, Kryvіy Rig, Bila Tserkva and Lviv used another 100-250 million m3. If all of those plants switched to bioenergy, it would potentially reduce Ukraine’s current needs in imported gas by at least one third. Nevertheless, nothing has been done over the course of the past five years.

This way, corruption and monopoly in the government as well as among current key gas business players have completely blocked Ukraine’s efforts to become self-sufficient and fully rely on its own gas production. As a result, reducing the prices for the internal market consumers has also not been an easy task.

An illusion of competition

First steps of on the way to reform power engineering industry in Ukraine were taken on 1 January 2019. State energy enterprises, also known to consumers in Ukraine as oblenergo, were replaced by two others types of companies: first, operator of the distribution network, a unit which was set up to solely transport the electricity, and second, the companies, which were designed to sell it to the final consumers. At the present time, there were over 300 of such electricity traders registered in Ukraine, and this amount will potentially increase for further few thousands. In July this year Ukraine expects to officially open the market of electricity wholesale. This market will consist of three different features. Bilateral agreements will enable arranging of the long-term contracts between the buyer and the seller. The “one day upfront” trade agreement will facilitate the purchase and the sale of the electricity within a day after the contract conclusion. The “24 hour” market will allow selling and purchasing the electricity within the 24 hour period of time. From now on Ukraine’s National Regulatory Commission for Energy and Utilities (NKREKP), which currently controls 100% of the price formation for both product and the service, will only control the transportation costs, because those are regulated by the natural monopolies.

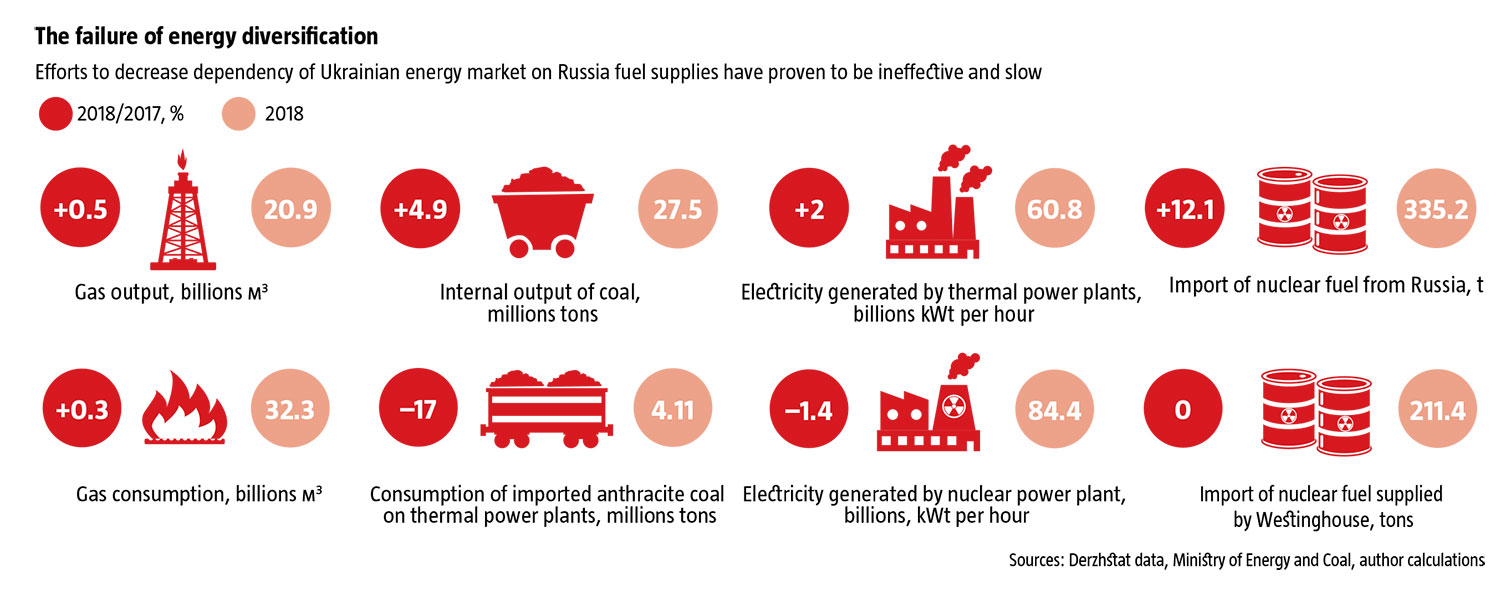

It may seem that a range of available options and consumer choices as well as the market competition are now at its best. This has only been the case for the final consumer, though. In point of fact, once this matter is studied more carefully, it turns out that introduction of the electricity trade market has concurred with numerous pre-existing problems in the energy sector, faced by Ukraine before – monopolies and the influence of the oligarchic lobby in the government. At first glance, one may think that the circumstances on the electricity market differ significantly from the ones in a gas sector, because not only Ukraine can fully satisfy its needs in electricity, but it also exports the remaining surplus. However, Ukraine’s electricity market and power engineering is heavily dependent on the import of fuel, necessary to operate power plants generating the electricity. Further, Ukraine imports almost entirety of its nuclear fuel needed to operate nuclear power plants (NPP). Those NPP satisfy nearly half of the country’s need in electricity. Additionally, Ukraine is forced to import anthracite coal (also known as hard coal), which still has no alternative on several thermal power plants. Production of the coal type “G” (‘gas coal’) is entirely monopolised by DTEK, a private strategic coal and energy holding in Ukraine, owned and controlled by the Ukrainian oligarch Rinat Akhmetov. According to the data provided by the Ukrainian Ministry of Energy and Coal, out of 27.5 million tonnes of coal produced in Ukraine in 2018, nearly 23.9 million tons were produced by the DTEK-owned mines. Additionally, DTEK’s power stations currently consume 80% of the gas coal in Ukraine.

How can we talk about healthy competition on internal Ukrainian market, if Akhmetov’s DTEK not only controls 87% of the energy coal production in the country, but also consumes majority of this coal to produce electricity? In the above-mentioned circumstances oligarchs’ ability to dictate their own terms, when it comes to electricity prices, hardly comes as a surprise. Companies, which will purchase this electricity to then sell it to private and business consumers, will be left with little leverage and will have no choice, but to agree to these terms. As a result, whether one likes it or not, intermediaries and electricity distributors will not be able to influence monopolistic prices set by DTEK.

On its lengthy journey from a coal mine to a power plant or the distribution company, Ukrainian coal passes through an endless chain of various offshore companies, which were designed to withhold and conceal immense profits. Currently, only imported fuel can compete with DTEK’s production in Ukraine, but it will naturally inflate the price of the final product, and, more importantly, will undermine any attempts to develop and grow coal and mining industry in the country. DTEK is not interested in production levels surge, since it will lead to market oversupply, and will reduce the prices as a result. The sole hypothetical alternative, presented in the “Law on electricity market in Ukraine”, is electricity import. It is not feasible due to several factors, such as political (imports from Russia would hardly be possible), or economic and technical (for instance, it is not economically sustainable to import electricity from the EU, since its more expensive, limited and it’s not always logistically easy to transport it to Ukraine).

Therefore the future of Ukrainian coal industry lies in complete de-monopolisation of the local output through compulsory division of DTEK’s coal and mining assets into three or four truly independent companies with independent owners, who would compete with one another. Should this happen, prices of coal, and later the electricity produced at thermal power plants, will be remarkably reduced. Additionally, the state should impose higher tariffs on coal production in order to put an end to the current schemes when vast majority of the profit remain in offshore accounts.

Having said that, it should be noted that monopolies on internal Ukrainian market is nothing compared to Ukraine’s unprecedented dependency on fuel, supplied by Russia, a wartime aggressor. Replacement of Russian nuclear fuel used by Ukrainian nuclear power stations has proven to be a very slow process. Moreover, in 2018 the share of Rosatom, Russian state nuclear energy corporation, on Ukrainian market grew up to 12%, while the share of an alternative provider, Westinghouse, American electrical corporation, has decreased. While in 2018 Westinghouse has supplied as much fuel as in 2017, its share, compared to the Russian one, has decreased.

According to the Ukrainian Statistics Bureau, out of 3.87 million tons of anthracite coal, which remains the only alternative fuel for several thermal and nuclear power plants and which is heavily imported from abroad, 3.62 million were supplied by Russia and only 0.25 million were imported from South Africa. We are talking about 92% dependency on Russian supplies, a number, which even outweighs the scale of DTEK monopoly.

In all honesty, it is worth saying that consumption of anthracite coal, and as a result its import, has recently decreased. While in 2017 Ukrainian thermal power plants consumed 4.95 million tons of this fuel, in 2018 this amount dropped to 4.11 million tons. This change was a result of refurbishment of several blocks at Zmiyivska and Trypilska thermal power plants, owned by the state Tsentrenergo, as well as Prydniprovska thermal power plant, owned by DTEK. Ultimately, in 2018 all thermal power plants owned by DTEK outside of the temporary occupied territories in Luhansk oblast, consumed some 1.42 million of anthracite coal, while the Luhansk thermal plant itself – 1.02 million tons. It also seems that Slovyansk thermal power plant has become a major black hole of corruption, burning nearly 1.63 million tons of Russian anthracite coal in 2018, despite that fact that this plant’s facilities weren’t that necessary and its output wasn’t very beneficial. Furthermore, it is also unclear who the real owners behind this plant are. From March until April 2017 Slovyansk thermal power plant was not operating and its output capacity was successfully replaced by Zaporizhzhya nuclear power plant.

In fact, it seems like the logic behind initial efforts to fight Akhmetov’s monopoly on internal Ukrainian market only facilitated to lobby fuel importers from Russia and caused further dependency on Russian anthracite coal. For example, numerous efforts of the Ministry of Coal and Energy to impose legal restrictions on importing fuel and prioritising local Ukrainian fuel were met with criticism and dismissed as “Akhmetov’s lobbyism”. Those critics’ arguments are quite weak, nevertheless. DTEK is indeed a monopolist on Ukrainian market, as was described above, and this company’s influence has to be dealt with in a right manner in order to remove an obstacle to the growth of Ukrainian coal industry. However, it is highly unwise to do it by simply increasing Ukraine’s dependency on Russian supplies, such as importing anthracite coal, especially when in the current circumstances this dependency may become absolutely pivotal.

RELATED ARTICLE: Slaloming the risks

Article 68 of the Ukrainian “Law on electrical power energy market” still says that “suppliers have to be chosen after considering minimal spending in relation to the output and consumption of electrical energy”. This naturally logical and financially feasible approach, does not, however, consider potential complications, which may appear without proper regulation of grave dependency on Russian fuel. One potential alternative may be either full ban on Russian anthracite or the gradual decrease of its consumption, for instance limiting its import to 2 million tons first year, then 1.5 million tons the second year, and then 1 million and 0.5 million tons in the next consecutive years.

Without solving the long existing problem of monopoly on electricity market in Ukraine, and problems relating to the current electricity generation in particular, all positive effects of recently introduced electricity trade will fizzle out. The sale of energy to the final consumer must be built on a solid ground – a highly competitive market of energy production and diversified fuel supply. If Ukraine’s internal market is monopolised by Akhmetov’s DTEK, and anthracite coal or nuclear fuel are imported from Russia, efforts to develop a new self-sufficient energy market and a sale of the electricity will be a fiction, aimed at only preserving monopoly as a phenomenon. This phenomenon will subsequently drive a decision or, potentially, indecision, to deal with the long existing issues, such as the will of oligarchy or energy dependency on Russia.

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook