The justification for NATO’s creation was once formulated as “keeping the Germans down, the Russians out, and the Americans in.” Given the dramatic geostrategic shifts over the past two decades, Europe’s new reality sees the Germans rising, the Russians infiltrating, and the Americans leaving. In this changing context, the German-Russian relationship will remain pivotal for Europe’s futur

STRATEGIC DEVOLUTION

The banking crisis in Cyprus took the lid of the simmering disputes between Berlin and Moscow. A rising Germany and an assertive Russia in the midst of increasing EU paralysis and steady U.S. withdrawal from Europe foreshadows a coming decade of competition. However, this will not be a contest for the conquest of territory but a struggle for the expansion of state influence.

Russia’s relations with the EU have deteriorated following Vladimir Putin’s return to the Kremlin last year. Putin once possessed three prominent friends in the Union: German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, and French President Jacques Chirac. His personal relations with current EU leaders, especially with Chancellor Angela Merkel, are poor and the formerly “special relationship” with Germany looks increasingly vulnerable.

Putin’s visit to Germany in early April took place against a background of rising bilateral political tensions. Although German-Russian trade reached a new record last year and energy ties are likely to deepen with the planned expansion of the North Stream natural gas pipeline under the Baltic Sea, political tensions are mounting. Indeed, Chancellor Merkel used the meeting with Putin to highlight Russia’s abysmal failings in respecting human rights and developing a democracy.

There are several drivers of escalating Russo-German frictions, evident in both the political and economic realms. Underpinning them is the resurfacing of a historic strategic rivalry for pre-eminence on the European mainland.

EUROPE’S HOUSE CLEANING

The Cyprus banking crisis raised the specter of an economic war between Berlin and Moscow. While EU officials are frustrated with the export of Russian corruption and how this infects a number of member states, officials in Moscow accuse the EU of outright theft in its handling of depositors accounts in Cyprus. The German-led bailout, to prevent the country’s bankruptcy, resulted in heavy losses for foreign depositors. The majority are Russians, estimated to have held around €30 billion. About $4 billion will be appropriated and the remaining deposits subject to rigorous capital controls. Much of this money is believed to be illicit revenue laundered through Cyprus.

Russian officials asserted that they might punish the EU for the Cyprus deal, for which Berlin is considered to be primarily responsible. Some Kremlin advisors wanted the assets of German companies operating in Russia, including Audi, BMW, Mercedes, Siemens, and Bosch, to be frozen or new taxes introduced on their assets. The German business lobby has been a keen supporter of rapprochement with Moscow; if the government puts any squeeze on their operations bilateral trade and investment will suffer and further undermine political ties.

READ ALSO: A Pipe of Discord

Although the conditions of the Cyprus bailout were heavily criticized in Russia, analysts believe that key Russian oligarchs and top executives of state enterprises were able to withdraw their funds in time and transfer them to other safer tax havens. Harder hit were Russian medium and small businesses that had set up accounts in Cyprus because of deep uncertainty over Russia’s financial system.

Beyond its financial bonanza for wealthy Russians, Cyprus has played a useful geo-political role for Moscow. The island has been a middleman for numerous Russian arms deals to countries such as Syria, Lebanon, and Iran, and during disputes with other EU countries the Kremlin was always able to rely on Nikosia’s support.

One of Germany’s aims, and that of other EU governments, in bringing Cyprus into line financially was to prevent Russia from expanding its strategic influences in the Eastern Mediterranean. During the course of negotiations on a banking bailout, the Cypriot government offered the Kremlin the use of a military base in the port of Limassol as well as a major stake in developing recently discovered offshore gas fields and participation in constructing a natural gas terminal. If realized, the former would increase Moscow’s military capabilities, while the latter could significantly increase its role in Europe's energy sector.

READ ALSO: The Confused Propaganda

In addition to cleaning Cyprus and other countries from Russian financial maleficence, Berlin is currently supporting investigations of Gazprom by the EU Commission for stifling competition in European markets. Gazprom’s use of energy as a tool of political influence and potential blackmail is no longer tolerated in Berlin. Its monopolistic control of supply and transportation of gas into Europe is increasingly challenged by EU officials. This has angered Putin and his business oligarchs who continue to view energy supplies as a major tool of Russia’s expansionist foreign policy.

HUMAN RIGHTS AND FOREIGN AGENTS

Berlin has also become more outspoken about Russia’s deteriorating human rights record. German officials and parliamentarians, together with several German NGOs, supported the anti-Putin protest movement that emerged in Russia during 2012. In retaliation, Russian police have targeted German NGOs promoting democracy inside Russia for allegedly endangering the country’s sovereignty. Two German political NGOs were recently raided in Moscow and St. Petersburg, and their operations paralyzed, prompting German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle to issue a strong protest with the Russian authorities.

A Russian law passed last July obliges foreign-funded NGOs involved in political activity to register as "foreign agents." Failure to comply is punishable by heavy fines or a prison sentence. Both the Konrad Adenauer Foundation and the Friedrich Ebert Foundation are now under police investigation. The former is closely linked to Chancellor Merkel's Christian Democrats (CDU), while the latter is related to Germany's opposition Social Democrats.

READ ALSO: Russia’s Soft Power Wars

CDU general secretary Hermann Groehe responded that “Germany’s political foundations are making an important contribution to the development of democratic structures, the building of a state based on law and the encouragement of civil society." German diplomats have warned that hampering the activities of German foundations could inflict lasting damage on bilateral relations with Russia.

Subsequent steps are very much dependent on the September Bundestag elections. The candidate for Chancellor for the Social Democrats, Peer Steinbrück, is a more traditional appeaser of Moscow and is expected to support steady ties with Russia regardless of its behavior. In recent interviews, Steinbruck claimed that Western democratic standards could not be applied to Russia, echoing the position of former Putin accomplice and Nord Steam chairman Gerhard Schröder. It is too early to predict the election winner, but Chancellor Merkel has the opportunity to outline a coherent strategic vision of Germany’s role in Europe to help retain power.

GERMAN SELF-ASSERTION

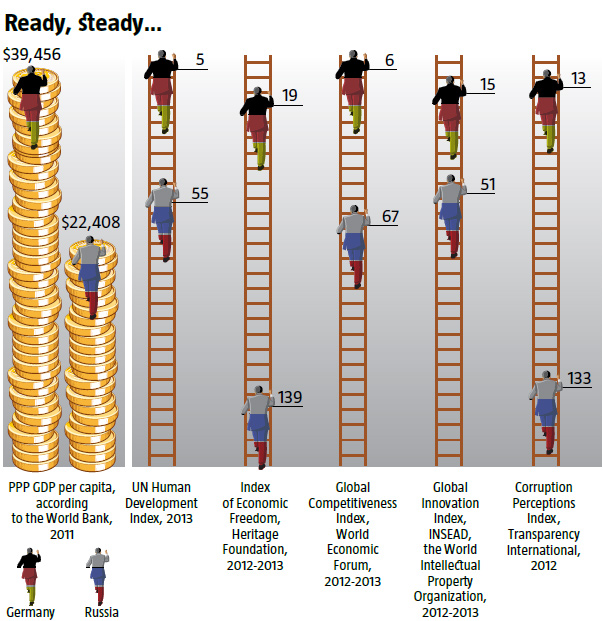

Several factors are raising Germany’s stature and self-confidence in a Europe that has been devoid of leadership for many years. These revolve around a reasonably consistent economic performance despite the EU-wide recession; political fractures within the Union that raise German authority as a decision-maker; U.S. military downsizing and its diplomatic focus outside of Europe; and a more assertive German national identity that will become more competitive with Russia.

One of the key objectives in building Europe-wide institutions after World War Two was to subdue German nationalism. But in the midst of Europe’s financial crisis and economic slowdown, German society appears to be turning against the EU project. A recent opinion poll conducted by the ZDF television network indicates that 65% of Germans think the euro currency damages the country, and 49% think that Germany would be better off outside the EU altogether. One in four Germans may be willing to vote for a party that wants to quit the euro as anger with the costs of the financial crisis is escalating.

A poll conducted for the weekly Focus magazine indicates that 26% of citizens may back a political party that would take Germany out of the eurozone. Tapping into growing Euro-opposition, a new movement styled as Alternative for Germany (AfD) recently held its founding convention in Berlin. AfD demands German withdrawal from the euro and return to the Deutschmark, or the creation of a separate currency with Holland, Austria, Finland, and other financially stable economies.

READ ALSO: Cold Peace

Germany's mainstream parties remain pro-euro and pro-EU, despite some internal protests over bailouts for southern European states such as Greece and Portugal. Chancellor Merkel has tried to reassure her voting base by insisting that heavily indebted countries must impose harsh austerity measures and pay back their debts. Her position has increased anti-German sentiments across Europe and raised charges of German chauvinism. The Social Democrats and Greens have backed Merkel’s approach in dealing with Europe’s financial problems, but the AfD is waiting for a significant boost if a new financial crisis materializes in the coming months.

Inconclusive election results in Italy have given fresh ammunition to AfD, with indications that the next government in Rome may backtrack on its austerity pledges. AfD leader Bernd Lucke has asserted that threats to default on Italy's external debt has demolished claims that Germany's rescue pledges will not be wasted. Similarly, the leftist Syriza movement in Greece, which has been polling ahead of other parties, also asserts that it will refuse to pay back Athens’ debts if it achieves power. As a result, the AfD sounds increasingly credible when it declares that "whether countries can and will pay back their debts is dependent on the unpredictable voting choices of their peoples." A combination of exasperation by German taxpayers and public resentment against anti-Germanism within the EU could start to push the country beyond the confines of the Union.

NEW ERA OF COMPETITION

German self-assertion combined with escalating economic and political divisions between northern and southern Europe can lead to the emergence of a stronger sub-European core led by Berlin and a subordinate EU periphery. Germany’s prominence will also directly challenge Russian ambitions toward Europe. Moscow seeks pliant governments that will support its strategic interests or will remain neutral.

The international arena will witness more frequent political battles between Berlin and Moscow. Conflicting interests in the Middle East, where Germany has lined up fully behind the U.S., has already been a major factor of tension. German officials resent Russia’s support of authoritarian regimes and may become increasingly critical of Moscow’s attempts to establish a Eurasian Union among the states of Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. Unlike the EU, such an alliance will be based on economic opaqueness, arbitrary government, and Russian oversight.

READ ALSO: The End of the Thaw: The West is Preparing For Confrontation With the Kremlin

The emerging strategic competition between Germany and Russia will not be based on ideologies of ethnic exclusivity or imperial expansion as during World War Two, but on contrasting principles of governance, rule of law, human rights, and economic discipline that will impact on the entire continent.

Janusz Bugajski is a policy analyst, author, lecturer, columnist, and television host based in the United States. He has published 18 books on Europe, Russia, and trans-Atlantic relations.