It was obvious at the end of 2019 that Zelenskiy team’s rating was falling despite situational fluctuations. This is perfectly natural in a democracy: history knows few cases where president or ruling party finished their term in office with a rating higher than what they had at the beginning. Most of the time, the opposite happens. Even re-elected leaders get back to their portfolios with ratings below what they had when they first entered office. This is not just because of their personal miscalculations: any elections fuel more or less inflated expectations that turn into bigger or smaller disappointments.

Zelenskiy’s team is in a more complex position as its political capital comes from the protest vote in the 2019 presidential and parliamentary elections. Despite the enormous result of the current government, the long-standing political fragmentation between the nominal East and West has not vanished. It is not impossible to overcome, yet it is based on factors far deeper than the mercurial protest sentiments. As the current government’s rating declines, this fragmentation will re-emerge. And the pro-Russian political camp seems ready to snatch new opportunities.

The 2019 election was painful for the pro-Russian forces as Zelenskiy’s team ruined the ex-Party of Regions’ political monopoly even in their core regions. Servant of the People won almost 30% in the Donbas, while its nominees beat local bosses in a number of constituencies. Yet, this is hardly ultimate and irreversible enlightenment of the local voters. It was pragmatic voting for many: they did not accept Petro Poroshenko’s course and supported his most popular opponent.

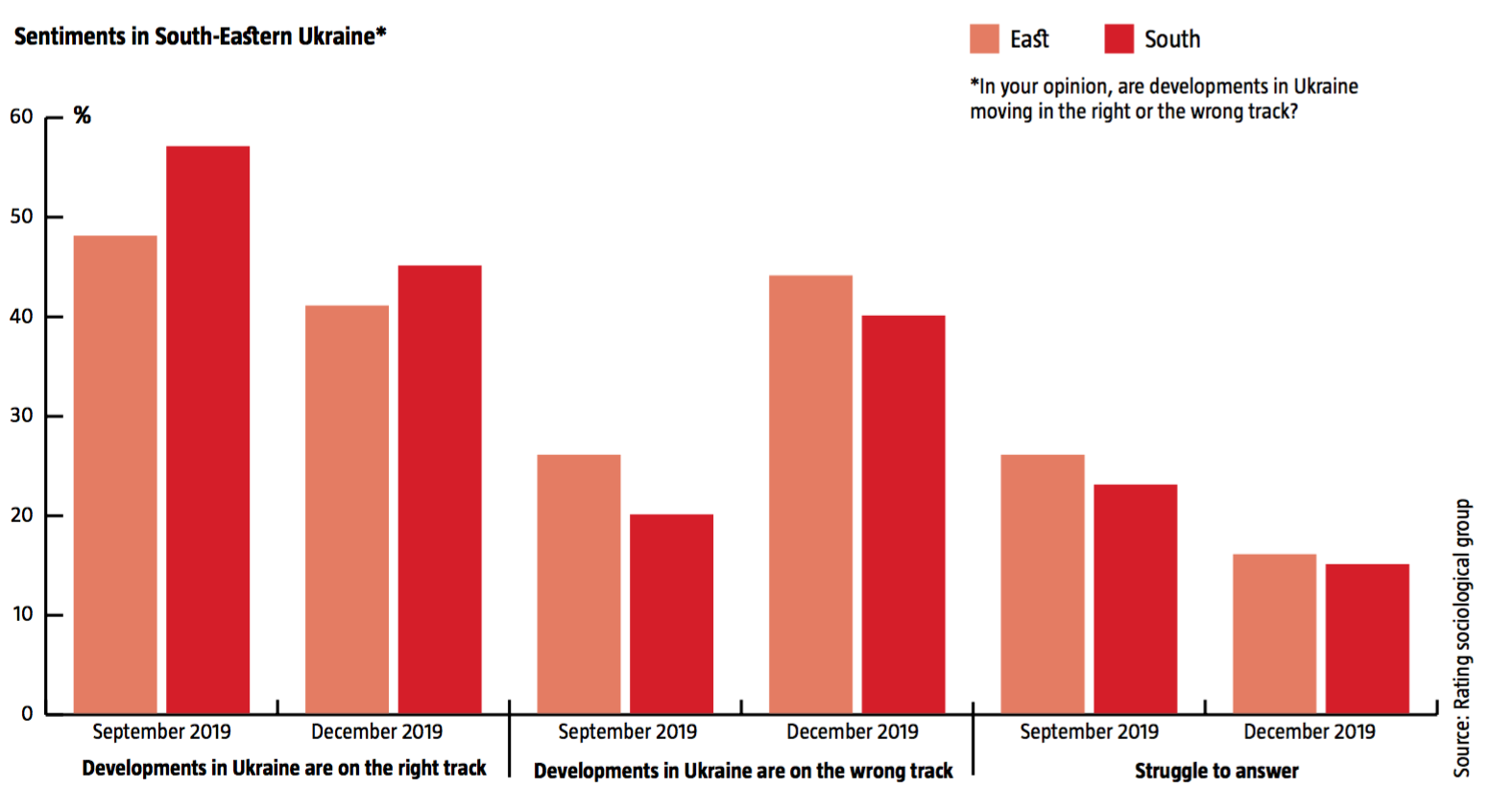

Given its good understanding of the south-eastern specifics, Zelenskiy’s team hinted at plans to change the “nationalistic” and “militaristic” policies. This was effective: similar shares of supporters of the nominally pro-Ukrainian Yulia Tymoshenko and the openly pro-Russian Oleksandr Vilkul (14-15%) were willing to vote for Zelenskiy before the presidential election, according to the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology survey. Whether the current government succeeds in transforming their 2019 spring and summer electorate into a loyal base for the long term is unclear. Frustration is already growing in Central, Western and South-Eastern Ukraine (see Sentiments in South-Eastern Ukraine). Among other things, this trend strengthens the demand for openly pro-Russian politicians.

Ex-Party of Regions is preparing to respond to this demand first and foremost. Despite the miseries they have experienced since the fall of the Yanukovych regime, declaring them politically dead is premature. Clearly, their electoral field was seriously curbed with the annexation of Crimea and the Donbas, and the chance of restoring former power is small. Still, they feel better than one could have expected after their political catastrophe in 2014 in their new niche as opposition. Moreover, they have seriously improved their electoral results in the past five years. Mykhailo Dobkin, Vadym Rabinovych and Yuriy Boyko ended up with a total of nearly 5% in the 2014 presidential election. In 2019, Yuriy Boyko and Oleksandr Vilkul gained almost 16% between the two of them in the first round, according to data from the Central Election Commission. Their results improved in parliamentary races too. Compared to slightly over 9% in the 2014 parliamentary election for the Opposition Block, over 16% of Ukrainians voted for the Opposition Block and the Opposition Platform in 2019. If not for the total domination of Zelenskiy and Servant of the People, the ex-Party of Regions would have landed a much better result. Therefore, they are already preparing for the next elections, beefing up their media assets and honing their social and “peacemaking” populism.

RELATED ARTICLE: Ze Nation

From the perspective of history, however, ex-Party of Regions is at an evolutionary dead end. Their core electorate is comprised of ideologically frustrated urban population of Ukraine’s southeastern Rust Belt, limited geographically and numerically. They are not capable of going beyond this frame. Nor are they ready to give up on their orthodox pro-Russian views. Their political narrative is Moscow-centric: it is for this reason that Boyko and Viktor Medvedchuk went to meet with Putin before the elections, despite potential electoral losses caused by this. In the late 2019, Medvedchuk announced a “broad assembly” of the Opposition Platform and Russia’s State Duma MPs, even though the Russian leadership does not enjoy much sympathy even in South-Eastern Ukraine. Ex-Party of Regions politicians are one-role actors following a script written for them in Moscow. Therefore, the biggest political threat for them would be for Zelenskiy to lean towards an “understanding with Russia”, stealing their core electorate and rolling into the narrow niche of south-eastern politicians. They have nothing to offer in response. In that regard, a strongly pro-Ukrainian Zelenskiy would work much better for the ex-Party of Regions.

Meanwhile, a new wing has emerged on Ukraine’s political scene that could strengthen the pro-Russian flank in the future. Zelenskiy’s victory has made it clear that the time of “authoritative politicians” with a long record in politics is coming to an end. Serious competition now comes from recognizable characters with charisma who are not even expected to have solid reputation as more voters are willing to vote “as a joke”. These are not the conventional populists playing on the sentiments of the miserable, promising them bread and circuses. It turns out that one can win elections without bread or promises. All it takes is to present yourself impressively. And it is no longer mandatory to buy thousands of billboards or hundreds of hours in prime time. Facebook, Instagram and YouTube perform these functions now.

Zelenskiy’s example has inspired many, including those hopeful with the pro-Russian electorate. Such figures are few in and around Ukrainian politics so far. Servant of the People’s Oleksandr Dubinsky is one example, known for his notorious statements and demonstrative friendship with Andriy Portnov, a representative of the Yanukovych regime, and Ihor Huzhva known for his prominent role in some pro-Russian media in Ukraine. Unlike Portnov who climbed a long ladder in the establishment, Dubinsky got into parliament as journalist and blogger, crushing his competitor Ihor Kononenko, formerly with the Poroshenko Administration, in a Kyiv constituency.

Anatoliy Shariy, another scandalous blogger and expat, hoped to walk the same path. He had some chances: Shariy’s YouTube channel has over 2.2 million subscribers compared to Dubinsky’s 339,000. While Dubinsky ran under the popular Servant of the People brand, Shariy managed to establish a party named after himself as the campaign was already ongoing. His party ended up with 2.2%, almost the same as Svoboda or Volodymyr Hroisman’s Ukrainian Strategy. Shariy’s Party was the most popular in Eastern and Northern Ukraine, and it crossed the threshold in Donetsk region. This localization is self-explanatory: Shariy built his name by criticizing the Maidan, ATO, “banderites”, Ukrainian government and more. Shariy himself failed to run in the elections: the Central Election Commission did not register him as he had not lived in Ukraine for the past five years. Still, his efforts did not go unnoticed. According to the law, his party will receive public funding, and his vlogs are now broadcasted at channel 112 associated with Medvedchuk. Both Dubinsky and Shariy are likely to try and mobilize the electorate which the ex-Party of Regions failed to reach in the near future, targeting primarily urban youth and the electorate actively following the media.

These politicians will not advocate for “friendship with Russia” openly by contrast to the ex-Party of Regions politicians. The discourse they promote today and will promote tomorrow stands on a different foundation. Firstly, this is anti-Maidan rhetoric that openly condemns the “junta” and the “coup”, or what sounds like rationalistic and sceptical rhetoric claiming that “things are more complicated than they seem.” Secondly, this is resistance to decolonization in domestic humanitarian policies masked as pseudo democracy that will utilize rhetorics about protection of minorities, ideological pluralism, historical truth, freedom of choice etc. Thirdly, this is resistance to consistent movement towards the EU and NATO. Agitating for any unions with Russia is an anachronism, so anti-Western rhetorics will be based on the criticism of “the decaying Europe”, exposure of “Soros- and Washington-funded” actors, and agitation for referenda. Fourthly, this is animosity against the patriotic segment of society, including volunteers, veterans, activists and journalists – all those who make sure that Ukraine stays on the path chosen after the Maidan.

RELATED ARTICLE: Feeling good

This framework allows them to build an image of critical and sceptical thinkers and reach broad audiences, including the superficially patriotic segments. In essence, though, these rhetorics play into Moscow’s hands just like the orthodox pro-Russian rhetorics did in the time of Yanukovych. In some aspects, this new trend is more dangerous than the dubious prospects of the ex-Party of Regions restoring itself: it may provide the pro-Russian camp with the prospects that could turn out more far-reaching than they seem.

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook