The exhibition project “MATERIA MATTERS. Ukrainian Art Textiles,” which spans all five floors of the Ukrainian House, aims to present artefacts created through creative practices over the past century. Curators Tetiana Voloshyna, Alisa Hryshanova, and Kateryna Lisova have opted to organise the spaces not by a linear timeline of techniques and imagery—such as carpet weaving, batik, embroidery, tapestry, collage, installation, appliqué, and other innovations—but by weaving together several visual narratives. Their intention is to offer viewers a glimpse into the most compelling, so to speak, pivotal moments of a century of Ukrainian art textiles—unique to our culture and this place.

This curatorial approach deliberately highlights that this uniqueness was created by distinguished artists. On the ground floor, the curators chose works—both sketches and completed textile pieces—by artists they consider crucial to Ukraine’s national heritage. The list of names is extensive but not exhaustive. In their detailed explanations, there is a noticeable effort (imbued with reverence) to reveal how these artists utilised the decorative potential of textiles. The sketches by Vasyl Krychevskyi and Serhiy Kolos, which were never realised as carpets or printed fabrics, serve more as metaphors for the unrealised potential that, under Soviet rule, could not be transformed into textile artefacts. This dramatic narrative is established from the start and, like Ariadne’s thread, weaves through the exhibition’s other thematic spaces, though not without what could be described as a “disjointed rhythm.”

For example, placing Ada Rybachuk and Volodymyr Melnychenko’s tapestry, which commemorates the tragedy of Babyn Yar and has been preserved in their studio since the late 1960s, alongside Oleksandr Roitburd’s ironic “Cardinal Richelieu” tapestry—created by anonymous artists for a 2018 exhibition project from Roitburd’s earlier collage—creates a striking contrast. The intense sorrow of Rybachuk and Melnychenko’s work, characterised by blue, pink, and soft yellow ribbons hanging like those from a wreath of an executed woman, is juxtaposed with the frivolous and headless figure of the “Cardinal Richelieu.” This combination is initially shocking but, after a moment of reflection, invites contemplation on the dramatic evolution of artistic tone and technique in Ukrainian art over the past fifty years.

One of the underlying messages in the collective curatorial statement, evident in the exhibition design, appears to be that Ukrainian art textiles served as a form of resistance against the Soviet regime. This theme is most strikingly represented on the third floor, where two rooms take centre stage. One of these rooms is intentionally sparse, featuring dim lighting and a screen displaying a looping video of a woman’s hands winding a ball of red thread. The few artefacts in this space are subtly illuminated on tables and walls, creating an atmosphere of persecution, confinement, and underground resistance.

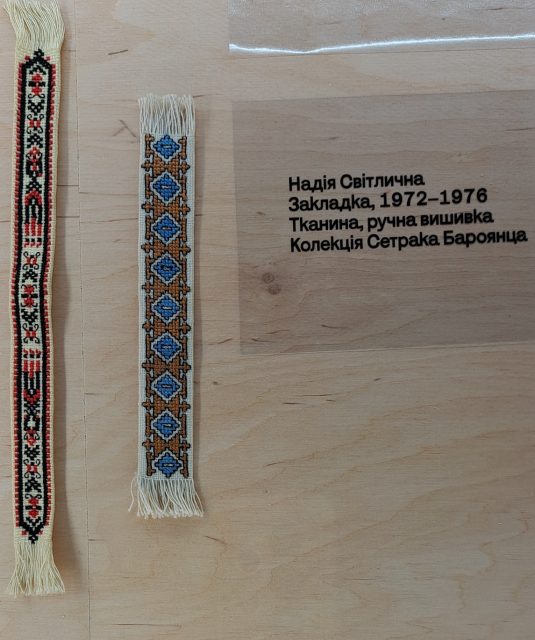

Standing by one of the tables, I felt a profound sense of reverence, as though witnessing a miracle made just for me. In 2009, I translated a poem by Ihor Pomerantsev dedicated to Nadiya Svitlychna for his book The KGB and Others. The author had known Svitlychna and her brother, Ivan Svitlychny, in the 1970s during their prison visits and correspondence. Seeing the physical manifestation of the poetic image I had worked on for fifteen years was a deeply moving experience. It stood as the most compelling testament to the exhibition’s motto from the main banner: “…materia [‘matter’ in Ukrainian – ed.] matters.”

To Nadiya

Dear,

The bookmark

you embroidered

with a Ukrainian pattern,

when they cast you into the punishment cell,

and which you later

gifted to me—

it rests in my notebook.

I want your name

to weave into these lines

with that Ukrainian pattern.

I want

every word I write

to resonate with your name.

The canvas bag, adorned with an embroidered patch marking the prison and cell number, crafted by Olha Matselyuk, is an artefact that invites reflection. Rather than focusing on how the simple cross-stitch came to dominate Ukrainian embroidery, displacing more complex techniques, it prompts us to appreciate its aesthetic simplicity. This simplicity serves to preserve and honour the dignity of Ukrainian identity.

The creativity of this bag, much like the miniature bookmarks, was expected to shine even more on the floor above, where works by artists who boldly resisted ideologised and clichéd imagery were displayed. From the photos I had seen online, I was excited to finally view in person the works of Oleksandra Tsehelska-Krypiakevych, Stefania Shabatura, and Liudmyla Semykina, which I had only seen in pictures before. However, the design choices and curatorial text for this section were a significant letdown. It wasn’t just the issue of window lighting on an August evening (or even a sunny day) turning many art objects into darkened smudges due to backlighting. It was particularly disheartening to see part of the unique Cassandra tapestry, for which Stefania Shabatura was imprisoned for her alleged “nationalism,” placed on the floor. Given the artefact’s immense value and historical significance and its debut exhibition in Kyiv, a more thoughtful presentation was warranted. This piece deserves careful interpretation, not only because it demonstrates the use of textiles for ideological and aesthetic resistance, especially in Lviv, but also because it currently lacks a serious analysis of its individual elements, texture, and colour. The accompanying text dedicates only a single paragraph to it. It is unclear why the curators did not address the absence of the “nationalism” that was once so perilous to the Soviet security services in the early 1970s.

The emotional and intellectual dissonance in this space stems not only from the limited and sparse presentation of Ukrainian art textiles history but also from its juxtaposition with other exhibits. On the main part of the third floor, contemporary art practices are displayed in a generous and cohesive manner. In contrast, the Soviet-era context is represented solely by the works of Liubov Panchenko and Oleh Mashkevych. Without the necessary political and aesthetic context, the concept of ‘textile resistance’ from the 1970s and 1980s remains perplexing, even to those familiar with the subject.

Intrigued, I hoped to find a deeper exploration of the Soviet-era “thematic carpets” on the floor above. These carpets were not only ideological tools but also a major source of income for textile artists working at large enterprises like the Reshetylivka and Hlyniany factories or the Darnytsia Silk Mill. For decades, their designs established “standards” for the mass perception of “textile material” as utilitarian and secondary, whether in carpets for public spaces (libraries, cultural centres, tourist complexes, theatres) or upholstery fabrics. Without this historical context, which shaped generations of artists who contributed to an image of a so-called “blossoming” of Soviet Ukraine, the struggle for a tragic national image remains opaque.

While the curators may have chosen not to include these ideologically charged artefacts under the umbrella of ‘art textiles’, there were other ways to address their significance. Publications such as books, booklets, journal articles, and exhibition catalogues, though not widely accessible, could have provided valuable context. Without these resources, understanding the origins of ‘Ukrainian millefleurs’ and the enduring appeal of floral compositions during Soviet times is challenging. On the fourth floor of the Ukrainian House, only a few artefacts were displayed near the stairs with minimal explanation, a stark contrast to the more comprehensive presentation on the first floor.

In broad terms, this project can be seen as a bold effort to spark a meaningful conversation about “Ukrainian art textiles.” However, it, unfortunately, suffers from notable gaps, akin to voids in some exhibits—whether from time-worn damage or deliberate design choices like lace-like connections or harsh cuts that disrupt the textile’s integrity. The exhibition, with its two nearly empty floors in an expansive space, feels like an exaggerated text that is either intentionally left incomplete or erased. This might provoke viewers to consider what is missing or suggest that the narrative is ongoing. These gaps can be interpreted as invitations to create anew, both in textile and in text.

It is unfortunate that so many art textile artefacts remain confined to museums and private collections, visible only to their owners and caretakers. It feels as though we, the viewers, have been transported back to medieval times when tapestries and carpets were woven solely to decorate the walls of castles and fortresses.