He crafted watercolours, sketches, and studies and composed songs and symphonies, but his true art was in writing. Mykhailo Kotsiubynskyi was a virtuoso of impressionistic prose, where language, music, and striking visual imagery converge. His literary legacy stands alongside that of poets like Mallarmé, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Verlaine, as well as the Norwegian author Knut Hamsun.

Portrait sketches

The eldest son of a minor government official, Mykhailo Kotsiubynskyi completed his theological seminary education but never realised his dream of attending university. The early death of his father compelled the young Kotsiubynskyi to take on the role of teacher and provider for his family. Despite these early challenges, he emerged as one of the most erudite figures of his time. Kotsiubynskyi forged friendships with the leading Ukrainian intellectuals of the era and mastered nine languages, including three Slavic and three Romance languages—French, Italian, and Romanian—as well as Tatar, Turkish, and Romani. His linguistic prowess complemented his work in translation, extensive travels, and active engagement in social and political spheres. He was notably instrumental in founding the “Prosvita” society in Chernihiv, an organisation dedicated to anti-colonial and pro-Ukrainian education.

For over a decade, Kotsiubynskyi navigated his daily responsibilities with unwavering commitment. At 34, he secured a stable role within the Chernihiv Regional Administration, moving from Vinnytsia to the city. By day, he fulfilled his duties as a civil servant, while by night and during his leisure time, he delved into his musical and visual literary pursuits. This dual existence, balancing public service with creative exploration, was keenly observed by his astute contemporaries.

In a snug collar, with a weighty case,

Neat and trim, in silence he paced.

Through his stern life he laboured long,

Over dreary charts and figures drawn.

(M. Rylsky, “Chernihiv Sonnets”)

Despite the challenges he faced, in his 48 years, Kotsiubynskyi crafted six major novellas and over twenty short stories, including a number of brilliant children’s works. Though the output might appear modest in quantity, each piece is imbued with distinctive and evocative imagery and symbolism that have left a lasting mark on Ukrainian literature. These works are not merely intriguing; they are deserving of the attention and discovery of an international audience.

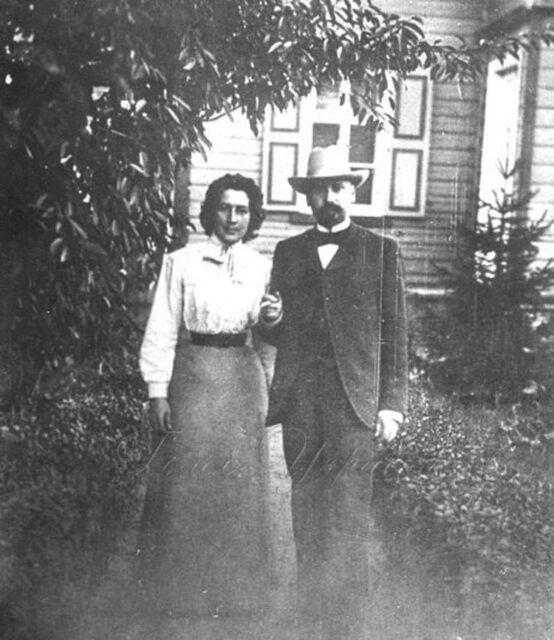

Photo: Mykhailo Kotsiubunskyi and his wife in front of their house in Chernihiv.

Who among us hasn’t felt puzzled, lonely, and weary?

These themes—or rather, these profound existential sensations—find vivid expression in Mykhailo Kotsiubynskyi’s works. In his seminal pieces “The Apple Blossom” (1902) and “Intermezzo” (1908), these sensations are depicted with remarkable power and innovation, allowing a thorough exploration of division, loneliness, and exhaustion.

In “The Apple Blossom,” a striking example of existential essayistic literature, the protagonist—a writer—confronts a life-altering moment: the death of his only daughter. Kotsiubynskyi adeptly captures the full range of a father’s emotions: profound sorrow, the flicker and eventual fading of hope, reconciliation, ineffable love, and despair. Yet, alongside these intense personal experiences, another dimension of the character emerges—his identity as a writer. Despite his anguish, he cannot ignore the beauty of spring unfolding outside his window or detach from the artistic perspective that colours his perception.

“I see the glassy, half-closed gaze, while my eyes and mind greedily absorb every detail of this dreadful moment… and record them… (….) To ensure nothing is forgotten… neither the ribs that, with each final breath, lift and lower the shroud… nor the golden curls scattered on the pillow… Everything will one day appear to me… as material… I hear it, I understand it; someone is speaking to me about this, another voice that resides within me…”

Finally, the closing chord: “The Apple Blossom.” (Interestingly, the apple blossom became a personal symbol for the writer—his friends brought them to his funeral. Flowers, in general, were a profound source of inspiration for him. As his daughter Iryna recalled, “He loved flowers, studied them with great enthusiasm, and possessed considerable botanical knowledge. In the garden surrounding our home, there was an array of flowers…”)

In The Apple Blossom, the author openly confronts and acknowledges emotions often deemed inappropriate, “incorrect,” or “inhumane.” He ventures beyond conventional limits to articulate and normalise—if not fully embrace—what a person may experience. The portrayal of fragmented self and duality in this work resonates deeply with many artists and writers, most notably inspiring Mykola Khvylovy’s I (Romantyka), where the protagonist grapples with the choice between his mother and allegiance to the ideals of the Soviet Communist party. Kotsiubynskyi himself faced the harsh reality of impossible choices—he harboured a profound love for another woman, Oleksandra Aplaksina, but chose to remain faithful to his family.

The theme of exhaustion from the “iron hand of the city,” vividly depicted in the short story Intermezzo, remains acutely relevant. This story, structured with symphonic precision, is noted by Yefremov for sharing similarities with Mozart’s C minor symphony. The characters, evocatively named My Exhaustion, the Sun, the Iron Hand of the City, and Human Sorrow, are introduced with the formality of a theatrical play, underscoring the story’s deep, existential engagement.

“Only packing remains… It is one of those countless ‘musts’ that have exhausted me and robbed me of sleep. Whether the ‘must’ is trivial or monumental, it relentlessly demands attention, turning me from its master into its servant. You become a mere slave to this many-headed beast. I long to escape it for a while, to forget, to find rest. I am weary. (…) I cannot evade people. I cannot be alone.”

Yet solitude in this context is neither a punishment nor an exile but a rare moment of harmony with oneself. The protagonist finds this peace by spending time alone amidst nature. The theme of unity and dialogue with nature is central to Kotsiubynskyi’s work, which may explain why, through his profound connection with the natural world, he is remembered in literary history by the evocative pseudonym Sun Worshipper.

Kotsiubynskyi’s enchanting portrayals of different cultures

Kotsiubynskyi’s exploration of Orientalism is a compelling topic that merits extensive discussion. His Orientalism is distinguished by a profound fascination with ethnographic studies and his research into the Turkic and Western Ukrainian mountain peoples. What sets it apart is the rare perspective he offers—one remarkably free of condescension. It is as though these peoples have chosen Kotsiubynskyi to be their voice.

Influenced by his experiences in Crimea and the cultural richness of Islam, Kotsiubynskyi crafted four thematic stories over the years: Under the Minarets, Into the Sinful World, On the Stone, and In the Shaytan’s Chains. In these works, Crimea emerges as a vivid, almost fantastical realm—self-sufficient and unique, untouched by the colonial policies of the Russian Empire. This evocative portrayal inspired the creation of Tatar Triptych (2004), the world’s first film in the Crimean Tatar language. Additionally, a museum dedicated to Kotsiubynskyi operates in Simeiz, located in Crimea, which is currently under temporary occupation.

During his treatments in Italy, Kotsiubynskyi crafted a series of Italian stories — Dream, Praise of Life, and On the Island. These narratives centre on the intimate relationship between humans and nature, focusing particularly on the elements of water, everyday life, and objects, with a recurring emphasis on plants. In On the Island, for example, the symbolism of the agave flower, which “blooms to die and dies to bloom,” mirrors the writer’s own contemplation of life’s cyclical nature as he neared the end of his own.

Kotsiubynskyi’s novella At Great Expense captures the Romani way of life with a blend of curiosity and wonder. However, it is his novella Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1911) — a poignant retelling of the Hutsul Romeo and Juliet — that stands out for its unparalleled power and craftsmanship.

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors: 113 years of timeless tales of life and love

In 2016, Kyiv witnessed a throng of hundreds queuing for one of the era’s most prominent exhibitions. This event celebrated the film directed by the acclaimed Armenian-Ukrainian filmmaker Sergei Parajanov, adapted from Mykhailo Kotsiubynskyi’s novella Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors. Having received numerous international accolades, the film is now featured in Harvard University’s essential film list for cinephiles. Parajanov reflected on his work: “I had long aspired to create a film that would fully unveil the poetic and gifted essence of the Ukrainian spirit. (…) We approached the Carpathians not merely as ethnographic subjects. Love, despair, solitude, and death—these were the frescoes of human existence that we sought to portray.” Parajanov’s choice of Kotsiubynskyi’s novella was a deliberate one, embodying his cinematic exploration of the Ukrainian soul.

The novella’s narrative is both elegantly simple and eternally resonant: Marichka belongs to a family at odds with Ivan’s clan, yet their love blossoms in secrecy. When Ivan leaves for work, Marichka tragically perishes in a flood. Upon his return, Ivan is unable to reconcile with his grief—even after marrying another woman, he roams the forests, haunted by visions of his lost love. Ultimately, he follows her spectral call and meets his end in a turbulent mountain river.

Photo: Georgiy Yakutovych, “Ivan and Palagna”, an illustration for Mykhailo Kotsiubynskyi’s novella “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors,” 1963.

Though Kotsiubynskyi’s tale may seem concise at first glance, it unfolds through the lens of Hutsul beliefs and mythologies (“true pagans,” as he termed them). The novella’s original text is written entirely in the Hutsul dialect, a language Kotsiubynskyi, from a different region of Ukraine, deliberately mastered. As such, the work primarily survives today as an adaptation. The author remarked, “If I could even slightly capture the essence of the Hutsul land and the scent of the Carpathians on paper, I would be content.” The novella employs techniques honed by Kotsiubynskyi: time and space are rendered as mythic constructs, the boundaries between the real and the fantastical are seamlessly blurred, and the narrative is enriched with vivid imagery, light and shadow, and auditory nuances. Moreover, Kotsiubynskyi’s preferred method of structuring his literary work as if it were musical adds a layer of fragmentation and cinematic quality. Since its publication, this work has inspired generations of writers.

Its influence goes well beyond literature. Besides Parajanov’s acclaimed film and a contemporary multimedia exhibition, the novella inspired a ballet by Vitaliy Kiriyenko in the 1960s and has been depicted by various illustrators, including Georgiy Yakutovych, whose linocuts are particularly notable. The novella also helped transform the small Carpathian village of Kryvorivnia into a popular tourist spot, featuring a museum-estate where the film was shot. The village is well-known for its stories that inspired this beloved Ukrainian saga of true love.

Photo: Mykhailo Kotsiubynskyi’s monument in the city of Vinnytsia