An economic recession accompanied by plummeting domestic and foreign demand, a declining hryvnia and pervasive uncertainty—these and other factors sent credit risks soaring two years ago, says Anastasia Tuyukova, an analyst with Dragon Capital, a Ukrainian investment company. Financial institutions have not managed to revive proper lending at acceptable terms since then, although the situation is clearly better in 2011 than it was in 2009, when only seven banks were issuing personal or commercial loans. Indeed, lending virtually disappeared from the market for a time as the share of deadbeat loans grew over 2009-2010 while the regulator restricted lending in foreign currencies.

These days, the government claims the economy is growing again. But the banking system, which was ever brisk to respond to positive macro indicators by stepping up lending prior to the crisis, is in no hurry now to support the real sector with extra hryvnia. And a stagnant credit market is one of the main reasons behind a decline in GDP.

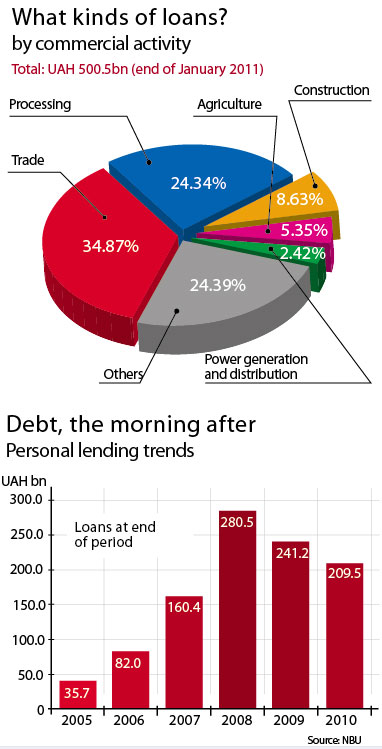

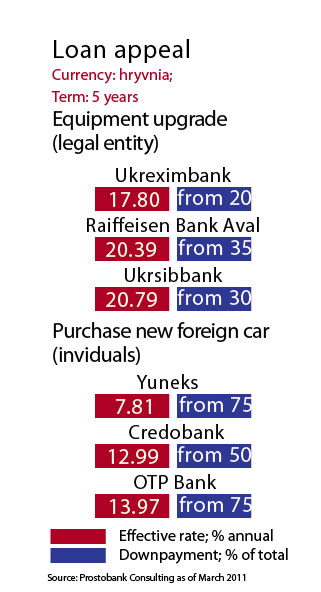

By early 2010, loan interest rates and terms were draconian and demand for borrowed money shriveled to nearly zero. In fact, lending remained alive only in bank flyers. According to Prostobank Consulting, a monitoring company, the real sector could borrow money to add to working capital or buy equipment on the basis of a micro credit at 31% interest in hryvnia and 23% in a hard currency—usually dollars—in 2010. By the end of 2010, these rates had fallen to 20-22% and 13%, but this failed to generate any demand. Businesses had few options to acquire capital to expand, while shrinking consumer lending and mortgaging put a crimp on sales of durables and cars—and nearly killed construction. According to the NBU, the gross added-value (GVA) of construction plunged 30% year-on-year in 2008, and another 40% in 2009.

So, what will the lending market look like in 2011?

For starters, Ukrainian banks are flush with cash. In August 2010, the balance on correspondent accounts hit a record UAH 34bn, or nearly US $4.3bn, while in January 2011, the NBU reported that personal deposits had risen to UAH 425.8bn, more than 30% more than in January 2010. Market participants say they had not expected such a boom in deposits and were forced to cut interest rates by 3-5% over the last year. Still, bankers learned lesson from the crisis and are not rushing to make loans cheaper despite the excess liquidity. They are counting to make money on securities, instead. Meanwhile, Ukrainians, having undergone their own credit hell and seen it happen elsewhere, are not eager to fall into the debt trap again, especially under the conditions being offered. These not only include extremely high interest rates, but terms that allow a lender to change the interest rate unilaterally as a standard contract provision.

So far, the NBU’s attempts to stimulate lending to the real sector have had little effect. Over 2008-2009, banks mostly used refinancing provided by the regulator for stabilization purposes, to buy foreign currency. But these cash flows never reached the real sector. In fact, refinancing made it possible to shift external corporate debt to sovereign debt. After some time, the NBU suspended these dubious subsidies but was unable to come up with anything new or more effective. Nor did the Government put together any clear lending priorities, including state-funded programs to subsidize loans.

In 2011, bankers promise that lending will intensify, but mostly commercial loans, as personal and consumer loans are considered too risky. “Our loan portfolio will grow largely due to corporate clients,” says Oleksiy Salyvon, Deputy COB at VAB Bank. “While mortgages will boost the retail loan portfolio, it will take much longer to pick up pace than car and consumer loans.”

Dragon Capital also expects its loan portfolio to grow by 15% in 2011, largely due to a 17% rise in corporate loans. As to retail lending, the decline will slow down over the first six months, analysts say, and lending will pick up again over the second six months, though only 4-5%.

According to market participants, banks have adjusted loan conditions based on their post-crisis experience. “A stable financial position, transparent incomes—and understandable, transparent financial statements from the corporate sector—, and a good track record are the key criteria in deciding whether to lend,” says Pavlo Tsetkovskiy, COB at Erste Bank. “The last couple of years have shown that collateral does not always protect a bank from losses if the borrower is unable to pay back, since chances are few that the assets will sell without a loss, especially if a property is foreclosed. The responsibility and financial stability of borrowers have become more important than collateral.”

Despite their traditional sanguinity and promises that lending will pick up pace for over a year now, bankers are still reluctant to make loan terms more reasonable. “For instance, personal lending intensified in the Czech Republic when interest rates froze at around 10% annually,” says Mr. Tsetkovskiy. “Getting to that point will be difficult in Ukraine, as long as the market offers deposits at 15%.”

Other measures needed to revive lending, such as taming inflation, allowing land market to operate properly, protecting lenders, and proper procedures for handling assets used as collateral, are still in the drafting stage. For most financiers, however, global uncertainty about the value of money and the prospects of the virtual economy, as well as the inability to assess the solvency of the real economy, are their biggest headache. Banks themselves have been mothballed.

Opinions

Natalia Lebedeva

Natalia Lebedeva

Deputy COB, Kyivska Rus Bank

In 2010, the key requirements for commercial borrowers included good financial performance and a solid business reputation. This year, by contrast, banks will care more about the prospects of the markets where companies operate and analyze their competitive positions and demand for their products. Banks will mostly lend to stable and promising industries, such as retail trade, especially petroproducts, the farm sector, food industry, pharmaceuticals, and oil industry.

We expect interest rates on loans to fall in 2011 as deposit rates are cut. Today, banks still have expensive deposits in their portfolios that they took on earlier. As soon as expensive capital is replaced by cheaper capital, there will be room to cut interest rates.”

Mykhailo Vlasenko COB, Astra Bank

Mykhailo Vlasenko COB, Astra Bank

Last year, the cost of borrowing went down significantly. For instance, interest on car loans was 25-27% annually in hryvnia at the beginning of 2010, compared to 16-18% now. Tougher competition and new players on the loans market will push consumer interest rates down an additional 1-3% over 2011. Interest rates cannot decline quickly because of the cost of capital on the market and the risk factor. In 2011, we expect Ukrainian banks to increase their loan portfolios in hryvnia by 20% and cut those in foreign currencies by 10%. The changing structure of the portfolio should lead to modest growth of 2-5%.

Overdue clients

Angry clients have come back to Rodovid Bank in long queues demanding their savings back. The panic started after Premier Azarov announced March 11 that personal deposits would be transferred to a state-owned financial institution, while Rodovid Bank would maintain only troubled assets. According to Ukrainskiy Tyzhden sources, nearly UAH 4bn of personal deposits are in limbo in the Bank’s accounts. This amount is almost equal to the total loans issued by Rodovid, UAH 4.5bn, of which 70% qualify as troubled. Since Summer 2009, Rodovid Bank has received over UAH 8bn in public money, including UAH 5.6bn to pay out deposits to clients of the troubled Ukrprombank.

The panic over Rodovid Bank could have unpleasant repercussions for the entire banking system, although it is groundless. Plans were anyway to return depositors their savings from the State Budget, so transferring accounts to a state-owned bank is changing six of one for half-a-dozen of the other, just as with Ukrprombank. Once again, the Government has been unable to force a bank to meet its liabilities before depositors by tapping into those entities that siphoned off its assets.

Top Three bank bankruptcies

Slovianskiy Bank (Zaporizhzhia)

Reasons: In 2000, Borys Feldman, the owner of a bank that was one of the Top Five in Ukraine by capital, ran in trouble with the Government. A criminal case was opened against him and depositors fled the bank. In January 2001 it was shut down. 97% of depositors received compensation worth a total of UAH 3.9mn.

Bank Ukrayina (Kyiv)

Reasons: One of the largest Ukrainian banks claimed UAH 308bn in losses in fiscal year 1998, after companies linked to its managers failed to pay back loans worth over UAH 1bn. The bank was shut down in 2001. Eventually, all deposits over UAH 10 ($2) or 88% were returned, totalling UAH 32.1mn.

Intercontinentbank (Kyiv)

Reason: Management crisis and change of shareholders when owner died and bank was put on market. Issued unsecured loans to associated entities or backed by promissory notes from shell companies worth UAH 25mn (US $5mn). Liquidation began in April 2006. Eventually, 97.4% of depositors were paid back a total of UAH 78mn.